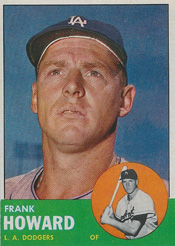

The first time Frank Howard came to the plate against the Cardinals he did what came naturally to him. He hit a home run. Not just any home run. A tape-measure clout, befitting a giant who stood 6-foot-7 and weighed more than 250 pounds.

As Jim Murray of the Los Angeles Times noted, “He’s Gulliver in a baseball suit.”

As Jim Murray of the Los Angeles Times noted, “He’s Gulliver in a baseball suit.”

A right-handed batter capable of launching balls into distant places, Howard ht 382 home runs in 16 years with the Dodgers (1958-64), Senators (1965-71), Rangers (1972) and Tigers (1972-73). He spent another 20 years as a big-league coach and managed the Padres (1981) and Mets (1983).

Hoops hot shot

In Columbus, Ohio, Frank Howard was “kind of a scrawny-looking, mangy-looking kid,” he told the Green Bay Press-Gazette. A son of a railroad machinist, he did construction work during high school and college summers. “I ran a jackhammer on asphalt crews,” Howard told the Press-Gazette, “and I was a hod carrier’s helper (carrying supplies to bricklayers). You work like that, and you’re going to have a strong body.”

When he enrolled at Ohio State, he was 6-foot-6 and 220 pounds. Basketball and baseball were the sports he played. “A lot of people thought I was better at basketball,” Howard said to the Press-Gazette.

In 1955-56, his first varsity basketball season as a sophomore, Howard averaged 15.1 points per game and led the Big Ten Conference in rebounding (12.9).

As a junior in 1956-57, Howard averaged 20.1 points and again was the Big Ten’s top rebounder (15.3). He snared 32 rebounds in a game against Brigham Young at New York’s Madison Square Garden. In Ohio State’s 74-54 home win versus the St. Louis University Billikens, Howard contributed 22 points and 11 rebounds.

In Howard’s senior year, Ohio State came to St. Louis’ Kiel Auditorium and he dazzled with 27 points and 10 rebounds, but the Billikens won, 88-77. Howard averaged 16.9 points as a senior and scouts for the NBA St. Louis Hawks “rated him as an outstanding pro basketball prospect,” The Sporting News reported.

New home

Howard played varsity baseball his sophomore and junior seasons at Ohio State and was “coveted by all 16 major-league clubs” because of his extraordinary power, the Los Angeles Times reported. According to The Sporting News, Dodgers scouts rated Howard higher than Dave Nicholson, the teenage slugger from St. Louis who signed with the Orioles for more than $100,000.

On March 5, 1958, the Dodgers signed Howard for $108,000. When he stepped into the batting cage for the first time at the Dodgers’ training camp in Vero Beach, Fla., Howard “was scared to death” and “actually was shaking,” according to the Los Angeles Times. On his third swing, he hit the ball 400 feet.

Teammates watched in wonder one morning when Howard consumed eight eggs, 24 strips of bacon, two bowls of cereal with sliced bananas, four glasses of orange juice and 10 slices of toast, The Sporting News noted.

The next month, the Philadelphia Warriors took Howard in the third round of the 1958 NBA draft, but by then he was on his way to the Dodgers’ farm club in Green Bay, Wisconsin. Playing for manager Pete Reiser, the St. Louis native and former Dodgers outfielder, Howard hit 37 home runs. “He’s simply fabulous,” Reiser told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. “He could do for baseball what Babe Ruth did. He hits many a ball completely out of sight in every park.”

Green Bay became important to Howard for reasons other than baseball. He met Carol Johanski, who worked in the circulation department of the Press-Gazette. She recalled to the newspaper, “We met in a pizza place in 1958. I was out with girlfriends and Frank and some fellows came over to our table and introduced themselves. We didn’t believe them when they said they were baseball players.”

Howard asked Carol for a date and they married a year later. Green Bay became Howard’s off-season residence. He spent several winters doing sales and promotional work for a Green Bay paper products company.

Big bopper

After his big season with Green Bay, Howard got called up to the Dodgers in September 1958. In his first game, he hit a home run against a future Hall of Famer, Robin Roberts of the Phillies. Howard’s blast landed atop the left field roof at Philadelphia’s Connie Mack Stadium. Boxscore

In the book “We Played the Game,” Dodgers reliever Johnny Klippstein recalled, “He was frightening looking and the strongest guy I ever saw in baseball, but he was mild and meek and called everybody Mister.”

Howard spent most of 1959 in the minors before a September promotion to the Dodgers, who were headed to becoming World Series champions.

The first time he faced the Cardinals was Sept. 22, 1959, at St. Louis. Batting for reliever Danny McDevitt, Howard drove a pitch from Lindy McDaniel 400 feet to left-center for a three-run home run. The Cardinals “couldn’t recall a ball that was hit as hard” as Howard’s line drive, the Post-Dispatch reported. Boxscore

Howard stuck with the Dodgers in 1960 after his recall from the minors in May, slugged 23 home runs and won the National League Rookie of the Year Award. On July 10, 1960, against the Cardinals at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, Howard had his first 5-RBI game in the majors. Boxscore

In a five-year stretch (1960-64), Howard led the Dodgers in home runs four times. He slugged 31 for them in 1962 and 28 the next year when they became World Series champions.

Howard hit .354 versus the Cardinals in 1961 and .340 in 1964. His home run against Craig Anderson in the 11th inning at St. Louis on July 22, 1961, struck the scoreboard in left, more than 400 feet from home plate. Boxscore

All was not well, though, for Howard with the Dodgers. Manager Walter Alston platooned him in right field and wanted Howard to change his batting stance in order to reach curveballs low and away.

Howard threatened to retire in 1964 and made it known he’d welcome a trade. The Dodgers accommodated him, sending Howard, Ken McMullen, Phil Ortega, Pete Richert and Dick Nen to the Washington Senators for Claude Osteen and John Kennedy on Dec. 4, 1964.

Washington monument

As the Senators’ everyday left fielder, Howard became “the most frightening home run hitter in baseball,” the New York Times noted. On a last-place team in 1968, he led the American League in total bases (330), home runs (44), extra-base hits (75) and slugging percentage (.552).

Ted Williams became the Senators’ manager in 1969 and Howard again was the league leader in total bases (340).

“That son of a gun is the biggest and strongest hitter who ever played this game,” Williams told the New York Times, “and that includes Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Jimmie Foxx, Hank Greenberg _ all of them. Nobody ever hit the ball harder and further, nobody.

“There was only one thing I talked to him about this spring,” Williams said. “He always used to swing at the first pitch that was anywhere near the plate. That’s just like swinging as if you had two strikes on you every time up. Wait. Wait for the pitch you want to hit.”

Howard, who never had more than 60 walks in a season, had 102 walks and 175 hits in 1969 _ an on-base percentage of .402. He was even better in 1970 (.416 on-base mark with 132 walks and 160 hits) and led the league that season in home runs (44) and RBI (126) in addition to walks. Video

Asked about Williams’ influence, Howard said to the New York Times, “He convinced me. I used to be swinging from the time I left the bench. Now I’m not afraid to give them a strike to be more selective … He’s made me more aware of what I’m doing as a hitter, and it has helped.”

Staying busy

After ending his big-league playing career with the 1973 Tigers, Howard returned to baseball as manager of a Brewers farm club in 1976. The next year, Howard became a coach on the staff of Brewers manager Alex Grammas. When Grammas was fired after the 1977 season, general manager Harry Dalton replaced him with George Bamberger. Howard told the Press-Gazette he was disappointed he was bypassed for the job, but Bamberger retained him as a coach.

Howard spent the ensuing winters in Green Bay operating a tavern. He described “Frank Howard’s Lounge” to the Press-Gazette as “intimate, the Fenway Park of saloons.” Howard tended bar and made it a point to talk with customers. As the Press-Gazette noted on a visit, “There he was, pulling on the beer taps, measuring shots of brandy, trying to stab olives and pouring delicate glasses of wine.”

In 1980, Howard’s fourth season as Brewers coach, George Bamberger took a leave of absence because of a heart condition. Howard wanted the job, but Harry Dalton gave it to another coach, Buck Rodgers. “It is tough to live with when you know you can do the job and no one else seems to know it,” Howard told the Associated Press.

After coaching for the 1980 Brewers, Howard was hired to be manager of the Padres, inheriting a last-place team. Howard’s 1981 Padres had Ozzie Smith at shortstop and a former Cardinal, Terry Kennedy, at catcher but not much else. Howard was fired after one strike-shortened season.

George Bamberger, who had replaced Joe Torre as Mets manager, hired Howard for a coaching job in 1982. The next year, Bamberger resigned in June and Howard replaced him. General manager Frank Cashen told Howard the job was only for the remainder of the season.

“He didn’t want to do it under those conditions,” Cashen told the New York Times, “but he finally acceded for the good of the organization … Nobody symbolizes professionalism more than Frank Howard did.”

Howard took over a last-place club. His shortstop was Jose Oquendo and a couple of weeks later the Mets got Keith Hernandez from the Cardinals to play first base.

Davey Johnson became Mets manager in 1984 and Howard was on his coaching staff. Howard went on to coach for the Mariners, Yankees and Rays as well as the Brewers and Mets again.

The bonus thing is so funny. The Dodgers gave Howard $108k in 1958, the Pirates gave Bob Bailey $175k in 1961, but the Giants wouldn’t give Barry Bonds $100k in 1982.

According to Sports Illustrated, Frank Howard asked for the $108,000 figure so that he could keep $100,000 for himself, and put $8,000 toward a new house for his parents.

What’s really strange is that he started putting up insane numbers after his 30th birthday, usually when numbers traditionally drop.

If I had a time machine right now you can bet my first destination would be Frank Howard’s dingy tavern on a wicked cold Green Bay day. I’d have a few beers take a few shots of whiskey and then I would be off to Yankee Stadium in the 1920’s.

Keep experimenting with those AI gadgets and you just might come up with that time machine, Gary. I’d go with you.

In a visit to “Frank Howard’s Lounge,” Len Wagner of the Green Bay Press-Gazette wrote, “He catches you coming in the door with a loud, ‘Hey, folks, great to see you here. C’mon in. Lots of room. Have some peanuts. We’ve got some cheese and crackers over there.’ Don’t worry if you have difficulty finding a couple of stools together. Frank will move somebody over, shift some stools around and get you seated, like a well-muscled, T-shirted maitre d’.”

Frank Howard had a genuine affection for Green Bay and its people. He told Tom Wheatley of the Press-Gazette, “My contention of a normal Green Bay person is they work their duff off, and then they go out and relax. They put in their 8 to 10 hours of hard day’s work, and then they like to have a couple of beers and a good steak. I think that’s a beautiful combination.”

Nice post Mark. It impresses me that Frank Howard got better the older he became. I say that because it gives me the impression that in his own way Frank Howard was a “student of the game.” Too bad we don’t see too much of that today. What he did with Washington is impressive taking into consideration that only once did they have a winning season. Also, in that period, pitching had the upper hand. Too bad he wasn’t eligible to play in the 1972 ALCS, a couple of at bats might have changed everything. Finally, it’s scary to think how his career might have gone had he talked with Ted Williams while still in his 20’s.

You make many strong points, Phillip.

Regarding Frank Howard’s production for the Senators at a time when pitching dominated, indeed, in 1968, when Howard had 44 homers and 106 RBI for a team with the worst record (65-96) in the major leagues, the average team ERA in the American League was 2.98.

Your mention of Ted Williams prompts me to ponder what Frank Howard would have done if he had played most of his career with the Red Sox at Fenway Park and that enticing Green Monster Wall in left. In 268 at-bats as a visitor at Fenway, Howard hit .291 with 18 homers.

Regarding Frank Howard not being on the American League Championship Series roster for the 1972 Tigers, Joe Falls of the Detroit Free Press visited him while Howard was packing his belongings in a downtown Detroit hotel room to prepare to head home to Green Bay while the Tigers were headed to Oakland for the playoffs. Falls wrote that Howard wasn’t unhappy or bitter about being left off the roster.

“I’m just glad I was in on this much of it,” Howard told Falls. “I knew what the situation was. I knew it would be over with the final (regular-season) game. I can’t feel badly about it. I got a lot more out of this than I put into it. I got a chance to see these guys up close. I got a chance to finally know Al Kaline. You know how Al is, so quiet and reserved. I always thought he was cold and aloof. Distant. So I come over here and find out how wrong I was. I see how he really does care about the people around him. I bet I went to dinner with him five times in this past month. It’s been my pleasure to spend just this little time with him. No, nobody owes me nothing. I owe an awful lot to the Tigers.”

Lastly, a personal note: The longest ball I have ever seen hit while attending a baseball game was one Frank Howard hit out of Tiger Stadium. The ball barely was foul but it carried over the roof in left field and went out of the ballpark into some distant place. It was a towering drive, the height and distance were incredible.

Frank Howard as a Dodger was a bit like Jack Clark in his Cardinal years – a power hitter on a team that mostly featured speed, defense and pitching. There is a photo I have seen somewhere taken with Howard and Maury Wills standing together – it is quite a picture as Howard looks about twice the size of Wills.

I recall being a teenager in 1968 and watching the NBC Game of the Week every Saturday – it was during that stretch when Howard hit something like 9 homers in a week, and Curt Gowdy mentioned during the broadcast that “Frank Howard has just hit another home run.” He was the talk of baseball for a little while that year, before the Gibson and McLain show.

Yes, indeed, in a stretch from May 12 to May 18, Frank Howard hit 10 home runs in six games for the 1968 Senators.

Los Angeles Times columnist Jim Murray told this tale about the time Frank Howard was at bat with the Dodgers and given the sign for a squeeze play with base runner Lee Walls on third: “He pays no more attention to signals than a bison frightened by lightning. When Walls dashed home, only to see Frank step into a pitch and swing mightily, he fainted dead away. They had to revive him to tag him out.”

Enjoyed this story. So many things here are hard to fathom. Try imagining Frank Howard as a scrawny kid. Or, try imagining anyone other than Joey Chestnut eating 24 pieces of bacon at one sitting. And it’s hard to think that one of MLB’s star sluggers had to pick up a sales job during the winter. What a throwback.

Frank Howard, who had six children, didn’t make a baseball salary of more than $50,000 until 1969. By 1981, he invested in Wisconsin commercial real estate, according to the Los Angeles Times.

Regarding the bartending he did at his lounge in Green Bay, Howard told the Times, “It’s been an education making me realize what a sheltered life I had.”

(The Monday through Friday specials from 4:30 p.m. to 6:30 p.m. at Howard’s tavern included 50-cent highballs and 75-cent cocktails, with beer on tap for a quarter, the Times reported in 1981.)

In a profile of Howard, the Times noted, “He calls himself just an ordinary working stiff, and he is very much at home in the working man’s town of Green Bay, whose legendary football team was named for a meat packing plant.”

Howard told the Los Angeles newspaper, “I’m no entrepreneur but I’ve tried to better myself for my family. I busted to do it … All I want out of life is a good steak, a bottle of beer and a good cigar … My dad never made $6,000 a year but our house was warm, our food was good and there was plenty of love in the family.”

I love that he worked in construction during high school and college and that he carried supplies to bricklayers. Who needs all the expensive weight training equipment!

It’s refreshing to know that he was scared when he first stepped into the batters box as a Dodger, refreshing in that we never know what’s going through someone’s mind, even a giant like Howard or a gentle giant in that he seemed so humble and polite and so willing to learn from the likes of Ted Williams. Amazing how much his walk totals spiked after Williams became his manager.

You are right about that humbleness, Steve. It seemed genuine.

In 1968, Frank Howard told John Devaney of Sport magazine, “That talk about Babe Ruth, it hurt me more than it helped me. I guess I can hit a ball as long and as hard as any man living, but not consistently. That’s always been my problem _ making contact with the ball. I’m only a fair to good hitter. I don’t try to kid myself. I know I will never be great. I do the best I can and accept what happens. I know my capabilities and I know my limitations.”

On the topic of his size being intimidating, Howard told the New York Times, “Never use the word ‘intimidate’ about me. Intimidation is something I don’t believe in. I let people know up front what I expect, and that’s all.”

A Brewers-related tidbit: When Howard was manager of the Spokane Brewers in 1976, two of his top players on that farm club were Kurt Bevacqua (.337 batting mark) and pitcher Moose Haas (13-9).