Johnny Klippstein was 16 when he pitched his first season of professional baseball in the Cardinals’ system. When he got to the big leagues at 22, it was with the Cubs, not the Cardinals.

A right-hander who converted from starter to reliever, Klippstein spent 18 years in the majors and pitched in two World Series _ one for the Dodgers and the other against them.

The Cardinals tried to reacquire him, along with a rangy first baseman who would become the star of a hit television series, but it didn’t work out.

Young and restless

Born at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, D.C., Klippstein was raised in suburban Silver Spring, Md. His father, who immigrated to America from Germany as a boy in 1894, served 30 years in the U.S. Army and retired as a master sergeant, according to the Brooklyn Daily Eagle.

A lanky kid with a strong arm, Johnny Klippstein learned to pitch in his one season playing American Legion baseball. In the summer of 1943, when he was 15, Klippstein and his mother took a bus to visit relatives in Appleton, Wis. By coincidence, the Cardinals were holding a tryout camp there and Klippstein went.

In the book “We Played the Game,” he recalled, “I arrived with a softball glove and softball hat and looked like a dope.”

Nonetheless, he impressed the Cardinals, who told him he would hear from them the following spring after he turned 16. With many young men in military service during World War II, ballclubs were reaching into the prep ranks to fill the talent pipeline. When Klippstein completed his junior year of high school, the Cardinals signed him and he was sent to their farm club in Allentown, Pa., in June 1944.

“All the guys were between 18 and 21 and I felt they were old enough to be my father,” Klippstein said to author Danny Peary. “The first time I went to the mound, I was so scared that my knees shook.”

Playing for manager Ollie Vanek (who a few years earlier gave a tryout to an amateur left-hander named Stan Musial and recommended him to the Cardinals), Klippstein pitched in six games for Allentown before spending the rest of the summer at a farm club in Lima, Ohio.

Afterward, Klippstein went back home to attend his senior year of high school. When he graduated in June 1945, Klippstein was so eager to return for a second season in the Cardinals’ system, “I didn’t even wait for my diploma. I told them to mail it to me,” he recalled to the Philadelphia Daily News.

Johnny on the spot

Klippstein, 17, was with Winston-Salem, N.C., for most of the summer of 1945. He posted an 8-7 record and led the team in ERA (2.48) but he also threw 19 wild pitches and hit batters with pitches eight times.

“He was rated (by the Cardinals) as a real prospect from the start, but he was young, didn’t even have his full growth,” the Winston-Salem Sentinel noted. “He was temperamental. He had a lot of stuff on the ball, but he was wilder than the usual rookie.”

Klippstein spent all of 1946 in the Army, returned to baseball the next year and pitched in the minors through 1948. After four years in the Cardinals’ system, Klippstein’s progress seemed to have stalled. As the Winston-Salem Sentinel noted, “The Cardinals did not want to let him go because they knew he had the stuff. They didn’t want to send him up because he was so wild.”

In the “We Played the Game” book, Klippstein said, “I was getting discouraged because I felt I was failing … The Cardinals didn’t have me in their plans.”

In November 1948, the Dodgers selected Klippstein in the minor-league draft. Sent to their farm club at Mobile, Ala., in 1949, he won 15 and had a 2.95 ERA.

The Cardinals wanted to get Klippstein back. In October 1949, Cardinals owner Fred Saigh met with Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey in Brooklyn and talked trade. The Cardinals offered pitcher Red Munger, a 15-game winner in 1949, for outfielder Gene Hermanski, first baseman Chuck Connors and Klippstein, the Associated Press reported.

(Connors, 28, made his big-league debut with the 1949 Dodgers, hitting into a double play in his lone at-bat. He later did better as an actor, playing the lead role of Lucas McCain in the TV Western series “The Rifleman.”)

Regarding the proposed trade, Rickey told the Associated Press, “Our greatest need is one more pitcher. I am willing to trade one of my outfielders for a good front-line pitcher. There is a chance to make that deal.”

Ultimately, the Dodgers decided to fill their need from within (Carl Erskine moved into the rotation in 1950) and the trade wasn’t made.

The Dodgers projected Klippstein for a spot with their Montreal affiliate, but the pitching-poor Chicago Cubs, who gave up the most runs in the National League in 1949, claimed him in the November Rule 5 draft.

In the big leagues

At spring training in 1950, Cubs manager Frankie Frisch said Klippstein would be part of the club’s pitching staff on Opening Day. “All he needs is confidence,” Frisch told the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. “He seems to have everything else.”

Klippstein had mixed results with the 1950 Cubs. He was bad as a starter (1-8, 7.99 ERA) and good as a reliever (2.98 ERA in 22 appearances) and as a hitter (.333 in 33 at-bats).

After the season, the Cubs acquired Chuck Connors from the Dodgers. He and Klippstein were teammates with the 1951 Cubs.

Klippstein did not have a winning record in any of his five seasons with the Cubs. He was sent to the Reds in October 1954 and had his most success as a starter with them.

On Sept. 11, 1955, Klippstein pitched a one-hit shutout against the Dodgers, who were on their way to becoming World Series champions that year. As Dick Young noted in the New York Daily News, “This was no humpty dumpty lineup. It had all the big sticks available.” Included were five future Hall of Famers: Roy Campanella, Gil Hodges, Pee Wee Reese, Jackie Robinson and Duke Snider.

The Dodgers’ hit came with one out in the ninth when Reese blooped a single to right-center. According to Dick Young, when the inning ended, Reese crossed paths with Klippstein, patted him on the rump and said, “Tough luck, John. It’s just one of those things.”

Klippstein just smiled at him. Boxscore

On the move

In 1956, his seventh year in the majors, Klippstein had his first winning season, finishing 12-11 for the Reds. On May 26, he held the Braves hitless for seven innings before manager Birdie Tebbetts lifted him for a pinch-hitter, with the Reds trailing, 1-0. (The Braves scored on a Frank Torre sacrifice fly after Klippstein loaded the bases by hitting Hank Aaron with a pitch and walking two.) Boxscore

“I don’t blame Birdie for taking me out,” Klippstein told the Chicago Tribune. “We were a run behind, had a man in scoring position, and only one more turn at bat.”

After a good spring training with the Reds in 1957, Klippstein was their Opening Day starter against the Cardinals. He got shelled, giving up five doubles (including two to Stan Musial). Boxscore

He ended the season much better than he started it. On Sept. 28, 1957, Klippstein pitched a one-hit shutout against the Braves, who were headed to a World Series title. The Braves’ hit was a Bob Hazle single with two outs in the eighth. Boxscore

Traded by the Reds to the Dodgers for Don Newcombe in June 1958, Klippstein was used mostly in relief the rest of his career.

In Game 1 of the 1959 World Series versus the White Sox, he pitched two scoreless innings for the Dodgers. Boxscore The Cleveland Indians obtained him in 1960 and he had an American League-leading 14 saves for them.

He went on to pitch for the Senators (1961), Reds (1962), Phillies (1963-64), Twins (1964-66) and Tigers (1967).

On Aug. 6, 1962, at Houston, Klippstein pitched three scoreless innings and walloped a Don McMahon slider for a home run, breaking a 0-0 tie with two outs in the 13th. Boxscore (Klippstein hit five home runs in the majors, but was hitless in 37 career at-bats against the Cardinals.)

He had a 1.93 ERA for the 1963 Phillies and was 9-3 with five saves and a 2.24 ERA for the 1965 Twins, who became American League champions. Klippstein pitched in Games 3 and 7 of the 1965 World Series against the Dodgers and didn’t allow a run. Boxscore and Boxscore and Video

For his big-league career, Klippstein was 101-118 with 65 saves.

After his playing days, he was a Cubs season ticket holder. In October 2003, Klippstein was listening at his bedside to a Cubs game (a 5-4 win over the Marlins) when he died. His son John told the Chicago Tribune, “He passed away just after the Cubs scored that fifth run” in the 11th.

I remember the 1965 World Series, through the eyes of a third grader, the Twins pitchers were “Mudcat,” “Kitty-Kaat,” Pasqual and the bullpen aces: “two old guys” (Klippstein and Al Worthington).

Johnny Sain was the pitching coach for those 1965 Twins. Johnny Klippstein said Sain taught him a slow curve in spring training that year to go with his fastball, the Minneapolis Star Tribune reported.

Al Worthington, 36, had 10 wins, 21 saves and a 2.13 ERA for the 1965 Twins. Johnny Klippstein, 37, had 9 wins, 5 saves and a 2.24 ERA.

Klippstein, whose 1965 Twins salary was $19,000, got a World Series share of $6,634.36. After the Series, he went to work at his off-season job as a salesman for a corrugated box company in Chicago, the Star Tribune reported.

From what I’ve read about him Johnny Klippstein was a wonderful individual and great to be around. Pretty amazing to think that at only 16 years of age he was already no longer eligible to play high-school baseball. Too bad he never seemed to find any long-term consistency. He certainly did have some very dominating performances. I also find it interesting how he himself says that maybe he fooled around too much with different pitches instead of simply relying on his fastball. Just a thought. Did the 1964 Phillies make a mistake in trading him?

You are correct about Johnny Klippstein having a reputation for being a good guy. Pitcher Jim Brosnan, who was Klippstein’s teammate with the 1954 Cubs and 1962 Reds, told the Chicago Tribune, “On and off the field, he earned a reputation as a hard-nosed nice guy who would knock you down on the field and then take you to dinner after the game.”

Before answering your question about the 1964 Phillies, here’s a story regarding an incident with the 1963 Phillies: On Sept. 22, 1963, in a game between the Phillies and Colt .45s in Houston, the score was tied 1-1 in the bottom of the ninth. Houston had runners on second and third, two outs, when Joe Morgan came to the plate against Klippstein. It was just Morgan’s second plate appearance in the majors, but he singled, driving in the winning run. In the clubhouse, Phillies manager Gene Mauch went ballistic, destroying the post-game dinner spread. According to Bill Conlin of the Philadelphia Daily News, Mauch then directed his anger toward Klippstein, shouting at him, “How could a veteran like you lose a game to a midget? How could you get your butt beat by a little leaguer?”

Klippstein began the 1964 season with the Phillies, but when pitcher Cal McLish (who had a bum shoulder) was taken off the disabled list in June 1964, the Phillies sold Klippstein’s contract to the Twins to open a roster spot for McLish (who was a favorite of Mauch). It indeed was a big mistake that cost the Phillies (who finished a game behind the National League champion Cardinals in 1964). Klippstein had a 1.97 ERA in 33 relief appearances for the 1964 Twins. McLish pitched in two games for the 1964 Phillies and was 0-1.

By the way, the Twins’ Calvin Griffith made two slick deals in the span of a couple of days in June 1964. On June 26, he purchased the contract of Al Worthington from the Reds. On June 28, he purchased the contract of Klippstein from the Phillies. Worthington and Klippstein were the top relievers for the 1965 American League champion Twins.

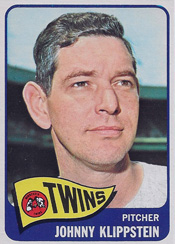

Johnny Klippstein was one of those guys we would get baseball cards for as kids in the ‘60s, but did not particularly care much about them. He had a long last name and with him being traded a lot, seems to have a lot of those dumb (in our opinion as kids) no hat or blacked out hat cards. But he hung around a long time. Great article – I did not realize he started in the Cardinals organization.

You’re so right about those Johnny Klippstein baseball cards, Michael. It seemed he was with a different team (and in a different pose) every year for a long while.

Like a lot of pitchers, Klippstein had his troubles against Stan Musial and Enos Slaughter. Musial hit .383 (23-for-60) against him. With 11 walks added to those 23 hits, Musial had a .479 on-base percentage versus Klippstein. Slaughter did even better. He hit .476 (10-for-21) against Klippstein and had a .577 on-base percentage when facing him (10 hits and 5 walks). Yet, Lou Brock batted .083 (1-for-12) versus Klippstein.

It’s hard to imagine two more challenging rites for a teenager than being in the pro ranks at 16 and then a world war. He seems to have had a really nice career, persevered and played for so many teams, maybe in the top 10 for most teams played for? I think the record is held by Edwin Jackson. I like how he managed to improve after tough seasons. He seemed to do it more than once, a sign of never giving up that is admirable.

Nicely said, Steve, about the ability to persevere and improve after facing adversity. It led to quite a long big-league career. In Johnny Klippstein’s first season (1950), his manager was Frankie Frisch, a Hall of Famer whose big-league playing days began in 1919, and in Klippstein’s last season (1967), his teammate was Al Kaline, a Hall of Famer who would play until 1974.

I really enjoy reading these stories about ball players who aren’t the big stars that everyone writes about. The level of commitment and perseverance that it took to become a major leaguer clearly comes through. And who can’t appreciate how much this guy loved the game.

Your comments are much appreciated, Ken.

As someone who followed the 1960s Mets, I thought you’d enjoy this anecdote involving Johnny Klippstein and a game versus the 1963 Mets:

On May 9, 1963, the Phillies played the Mets at the Polo Grounds. As Dick Young noted in the New York Daily News, “It was a lazy, hazy summer day. The humidity hung heavy; so did the bats in the hands of the Mets. They had no snap.”

With the Phillies ahead, 2-0, entering the bottom of the ninth, the Mets suddenly rallied and tied the score, 2-2. They had the bases loaded, two outs, when Cliff Cook batted against the third Phillies pitcher of the inning, Klippstein.

Here’s how Dick Young described what happened next:

“Cookie looked at a strike, tight, then took a check swing at another. Ahead of the hitter, 0-and-2, Klippstein decided to waste one, outside. It was such a waste. It flew past catcher Bob Oldis’ lunge and to the screen _ and home swooshed pinch-runner Al Jackson, so elated, that he went across in a storming slide, although there was no play on him. Thus did the Amazins cop their fourth straight win and hop back into eighth place. They are playing .444 ball, best in their life.”