During the 18 seasons he performed in the majors, left-hander Claude Osteen pitched 40 regular-season shutouts, the same total as Sandy Koufax and more than Lefty Grove (35) and Lefty Gomez (28).

That doesn’t count the unofficial shutout Osteen crafted for the Cardinals.

That doesn’t count the unofficial shutout Osteen crafted for the Cardinals.

On Aug. 15, 1974, the Cardinals acquired Osteen from the Astros for minor-league pitcher Ron Selak and a player to be named (another pitching prospect, Dan Larson).

Rusty from inactivity and unable to find a groove, Osteen didn’t produce a win for the contending Cardinals, but he did deliver a special performance in a remarkable game.

Entering in the 14th inning, Osteen held the Mets scoreless until the 23rd _ 9.1 innings, or basically the equivalent of a complete game. Though he departed with the score still tied, the Cardinals eventually won in the 25th.

Prep phenom

Osteen was born in Caney Springs, Tennessee, a hamlet 45 miles south of Nashville. As The Tennessean newspaper noted, “Almost everybody who lives in Caney Springs is kin to Osteen.”

Growing up there, he played baseball in cow pastures, learned to throw a curve and advanced to a 4-H Club team when he was 12. At 14, he moved with his family to Cincinnati, where his father took a job with General Electric.

Pitching for Reading High School, Osteen was 29-3 in three varsity seasons, including 16-0 as a senior in 1957 when his team became state champions.

Though his high school coach scouted for the Dodgers, who made an offer, Osteen accepted a contract with the Reds on July 2, 1957. “I signed with Cincinnati for several reasons,” Osteen told the Nashville Banner. “My folks wanted me to, for one. Besides, (the Reds) promised me I could stay with the club for a while instead of going right out to the minors.”

(Cardinals general manager Frank Lane said to the Cincinnati Enquirer, “We were interested in Osteen, but not to the extent of … putting him on our roster.”)

Major step up

Four days after signing, Osteen, 17, made his big-league debut against the Cardinals at Cincinnati. Si Burick of the Dayton Daily News described him as a skinny southpaw, “his cap cocked on the side of his head,” who “doesn’t look strong enough to throw the ball to the plate.”

According to Earl Lawson of The Cincinnati Post, Reds pitcher Art Fowler, 35, took one look at Osteen warming up and said, “My son can throw harder than he can.”

Cardinals backup catcher Walker Cooper, 42, told Osteen, “Little Leaguers are supposed to pitch from 40 feet out,” Lawson reported.

Entering in the seventh inning with two on, one out and St. Louis ahead, 10-3, Osteen faced five batters. He retired two, walked one, gave up two singles, threw a wild pitch and yielded a run. “A lot of fun,” he told the Enquirer. “I was a little nervous and I thought I might have been worse than I was, but it was a thrill.” Boxscore

(Catching the rookie from Caney Springs, Tennessee, that day was Ed Bailey from Strawberry Plains, Tennessee.)

The next day, Osteen faced the Cardinals again and pitched a scoreless ninth. Boxscore

Having fulfilled their pledge to let Osteen experience the big leagues, the Reds sent him to their Nashville farm club managed by Dick Sisler, the former Cardinal. Called back in September, Osteen made one scoreless relief appearance against the Cubs, striking out Ernie Banks with the bases loaded. Boxscore

Good moves

Osteen spent most of the next two seasons (1958-59) in the minors. Primarily a reliever with the 1960 Reds, he had a 5.03 ERA and was demoted the next year.

Osteen never got a win for the Reds. Other pitching prospects, Jim Maloney and Jim O’Toole, advanced ahead of him. In the book “We Played the Game,” O’Toole said, “I didn’t let anybody push me around like they did Claude Osteen. He’d throw what the catcher wanted instead of his best pitches and get hit hard.”

In September 1961, with the Reds on their way to winning the pennant, Osteen, 22, was traded to the Washington Senators, an American League expansion team. The Senators finished in last place in each of Osteen’s first three seasons with them (1961-63) but he got to start regularly and figured out how to survive.

“The big difference in my pitching now and when I was in the minors and with the Reds is I no longer try to strike out a lot of guys,” Osteen told the Nashville Banner in July 1962. “I realize I can’t strike out everybody up here. So I’m just trying to make them hit a bad pitch and let my fielders do some work.”

Osteen’s breakout season came in 1964 when he won 15 for the ninth-place Senators (62-100). Afterward, the Dodgers acquired him in a deal that sent slugger Frank Howard to Washington. The move vaulted Osteen from baseball’s basement into a starting rotation with Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale.

Hollywood material

When he joined the Dodgers, Osteen’s teammates nicknamed him Gomer because they thought he resembled actor Jim Nabors, who played the character of Gomer Pyle on “The Andy Griffith Show” (1962-64) and then on “Gomer Pyle: USMC” (1964-69). “One day, Jim Nabors comes to the clubhouse and we start talking about all that downhome stuff _ he’s from Alabama _ and doggoned if we didn’t become good friends,” Osteen told the Los Angeles Times.

Osteen (15 wins, 2.79 ERA) joined Koufax (26 wins, 2.04) and Drysdale (23 wins, 2.77) in forming a formidable top of the rotation for the 1965 Dodgers, who dethroned the Cardinals as National League champions.

After the Twins beat Drysdale and Koufax in the first two games of the World Series, Osteen turned the tide with a shutout in Game 3. The Dodgers went on to win the title in seven games. “If Claude hadn’t beaten us in that third game, we’d be the world champions,” Twins first baseman Don Mincher told The Tennessean. Boxscore

The Dodgers repeated as National League champions in 1966 (Osteen won 17 and had a 2.85 ERA) but were swept by the Orioles in the World Series. In Game 3, Osteen allowed one run in seven innings but Wally Bunker pitched a shutout and the Orioles won, 1-0. Boxscore

Osteen was a 20-game winner for the Dodgers in 1969 and again in 1972. He had double-digit wins in each of his nine seasons with them. “He is as dependable as sunset,” Jim Murray wrote in the Los Angeles Times.

Dodgers manager Walter Alston told The Tennessean, “There’s not a more reliable guy around … He gets about as much out of his stuff as anybody in the majors.”

In 1973, Osteen was 16-6 for the first-place Dodgers with one month remaining in the season, but he lost his last five decisions and the club went 12-14 in September, finishing second to the Reds. Afterward, he was traded to the Astros for outfielder Jim Wynn.

Houston, we have a problem

Osteen was the Astros’ first $100,000 salary player and was expected to make them contenders. [The highest-paid player in 1974 was White Sox slugger Dick Allen at $233,000, according to the Miami Herald. Leading the 1974 Cardinals: Bob Gibson ($160,000), Joe Torre ($140,000), Lou Brock ($110,000).]

One of the foes Osteen did best against in 1974 was the Cardinals. He beat them with a complete game in May and did it again in July. Osteen entered the all-star break at 9-7 with a 3.15 ERA. Boxscore and Boxscore

Though his fastball wasn’t sinking, and his curve and slider were hanging, “I was winning mostly on know-how and moving the ball around,” Osteen told The Sporting News.

Following the break, Osteen started twice and got shelled. He didn’t appear in a game for the next 17 days. “It was a very frustrating thing for me to find myself sitting on a bench,” Osteen told The Tennessean.

On Aug. 15, in a game against the Cubs, Osteen was told to get ready to relieve J.R. Richard. While Osteen warmed up, manager Preston Gomez waved for him to come to the dugout. “That’s when he took me aside and told me the deal had been made” with the Cardinals, Osteen told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

Stranger things

The first-place Cardinals projected Osteen, 35, as a replacement for ailing starter Sonny Siebert. Cardinals general manager Bing Devine “told me he had not bought my contract merely to have me help them finish out the 1974 season,” Osteen said to The Tennessean. “He said he thought I had a couple of more good years. I agree with him.”

In his Cardinals debut, a start against the Braves, Osteen couldn’t protect a 5-0 lead and was lifted in the fourth. For the 14th time in his career, Hank Aaron hit a home run against Osteen, sparking the Braves’ comeback. Boxscore

Moved to the bullpen, Osteen was used mostly in mop-up roles. As a starter, he’d developed a rhythm, knowing he’d pitch every four days. This was different.

“I had no idea how to go about being a reliever,” Osteen said to United Press International. “I didn’t know how to warm up, how long to warm up, how to get used to sitting around, waiting so much. At first, I found I was wearing myself out getting up and down (and) throwing.”

One and done

In a game against the Mets, Cardinals manager Red Schoendienst turned to Osteen in the 14th inning. Pitching like he had in his prime with the Dodgers, Osteen held the Mets scoreless until being relieved by Siebert with two outs in the 23rd. The Cardinals won in the 25th when Bake McBride scored from first base on a wild pickoff throw.

Osteen’s line: 9.1 innings, no runs, four hits, two walks. Boxscore

That was Osteen’s highlight as a Cardinal. He made eight appearances for them and was 0-2 with a 4.37 ERA. Osteen called the 1974 season “a totally lost year” and “confusing,” the Post-Dispatch reported.

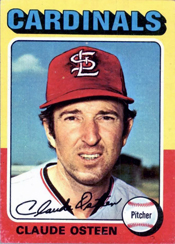

At Cardinals spring training in 1975, Osteen was “a prime candidate for the job as No. 5 starter,” according to the Post-Dispatch.

The Cardinals, though, had acquired another veteran left-hander, Ray Sadecki, 35.

Osteen posted a 3.91 ERA in 23 innings during spring training. Sadecki had a 9.00 ERA in 13.2 innings, but the Cardinals opted to keep him and release Osteen. Sadecki is “used to coming out of the bullpen,” Red Schoendienst explained to the Post-Dispatch.

Cardinals coach

Athletics owner Charlie Finley said a deal to sign Osteen “is virtually completed,” the Oakland Tribune reported, but the White Sox swept in and got him instead.

Osteen, 36, made 37 starts for the 1975 White Sox but lost 16 of 23 decisions in his final season. His career record: 196-195, 3.30 ERA.

Osteen bought a chicken farm near Hershey, Pa. During the 1976 baseball season, he was pitching coach for the Phillies’ farm club in Reading, Pa.

In October 1976, the Cardinals hired Vern Rapp to replace Red Schoendienst as manager. Osteen was surprised when Bing Devine called, asking him to meet with Rapp in New York during the 1976 World Series to discuss the Cardinals’ pitching coach job.

“I had never met Rapp,” Osteen said to The Tennessean. “I spent about three hours with Vern, talking about pitching. Before we finished, he picked up the telephone and called Bing and told him I was the man he wanted.”

Osteen spent four seasons (1977-80) as Cardinals pitching coach. He had the same job with the Phillies (1982-88), Rangers (1993-94), Dodgers (1999-2000). Three Phillies pitchers won Cy Young awards with Osteen as their coach _ Steve Carlton (1982), John Denny (1983) and Steve Bedrosian (1987).

Great research as always Mark. It struck me how successful Claude was in high school, like most players and then having to kind of start all over in the minors with such a spike in competition. I’d never heard of a player or pitcher having “must pitch in majors” chiseled into their contract. Nice that the Reds followed through with their promise.

Excellent that a lesson was learned in the minors – to try and not strike out everyone because it wasn’t in him and “to let my fielders do some work.” On the flip side, I was watching the Twins and Cubs yesterday and the Cubs announcer made a good point…..something to the effect of a strikeout minimizes unpredictability and that room for error. Kind of obvious but it hit me as important. Either way, from a fan’s perspective I prefer what Claude said, to involve the defense. Much more fun to watch.

While reading this, I couldn’t help thinking about Koufax and Greg Maddux and the time it sometimes takes for pitchers to hone their craft and also, interesting how he struggled as a reliever. Nowadays, so many former starting pitchers make that transition smoothly. But Claude had a very underrated career.

Lastly (sorry to be so long today), I never understand why pitching coaches move from team to team and never stay put. I mean there are exceptions like I think Dave Duncan and La Russa stuck together for many years on both Oakland and St. Louis, but it just seems strange to fire a coach if he’s been successful.

I enjoyed your comments, Steve, and glad you shared them all. I think you’ll appreciate the following insights on Claude Osteen’s assets as a pitching coach. The Philadelphia Daily News called him “a master mound technician who preaches proper mechanics as a requisite for a long and successful big-league career.” Osteen also told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, “You have to work on a pitcher’s mind as well as his arm.”

In describing his methods as a pitching coach, Osteen said to Bill Lyon of the Philadelphia Inquirer, “You do have to be a good psychologist. I don’t have any degrees in psychology, but I feel like I’ve had a lot of on-the-job training. I’m also very heavy on mechanics, angle of delivery, arm action, working what I call the rectangle of the strike zone. What I’m after is consistency. A pitcher has to groove his delivery just like a golfer has to groove his swing. Pitching is a continual battle against the count.”

Thanks for posting the quote Mark. It says a lot and has me thinking that it’s truly a mentorship between pitching coach and pitcher (similar to a hitting instructor and hitter) and if it lacks a meaningful connection, things can go awry.

Thanks for posting this Mark. I always enjoy reading up on players from another era who always considered themselves to be students of the game and with the attitude that there’s still something to learn.Claude Osteen was one of those players. He makes some very candid comments about today’s game. How coaches and scouts seem to be only interested in young guys throwing heat. Real pitching has become a lost art. While maybe it didn’t seem like it at the time, being traded to the lowly Senators was probably the best thing. He now had an opportunity to pitch regularly and develop his skills. Talk about pitching the game of your life in that 3rd WS game of 1965. That 25 inning game against the Mets is one for the ages. It’s interesting. Claude Osteen’s performance that night kept the Cardinals in the race. And yet, earlier in the year, when he was with the Astros, he beat us twice. Just a couple of things about that 25 inning marathon. Yogi Berra is probably the only manager in the history of the game to get thrown out in the 20th inning! And finally. It’s a good thing that the rules committee had made a modification to the balk rule. Otherwise, Bake McBride would have been forced to stop at 2nd base. Who knows when that game would have ended.

Regarding your astute comments about “student of the game” and “pitching as an art” rather than just heaving fastballs, Phillip, I thought you’d appreciate the influence Claude Osteen had on young pitchers, even before he became a pitching coach.

According to The Sporting News, when left-hander Randy Jones was 13, his school principal arranged for him to meet Osteen. They went to a sandlot and Osteen gave Jones tips on pitching. Jones went on to win a National League Cy Young Award with the Padres. “I still grip the breaking ball the way Claude taught me,” Jones said. “He told me then how important it was to keep the ball down and throw strikes.”

When left-hander Ken Brett was a youth in the Los Angeles area, he studied how Osteen pitched. Brett went on to pitch in the majors. “I always admired the way Osteen competed,” Brett told The Sporting News. “He helped himself in so many ways. He didn’t have overpowering stuff, but he always seemed to have a chance at a victory late in the game.” (By the way, Ken’s brother, George Brett, hit just .176, 3-for-17, against Osteen, even though he faced him when Claude was nearing the end of his playing days.)

Left-hander Doug Rau, who succeeded Osteen in the Dodgers’ starting rotation, said to The Sporting News, “I want to be a guy like Osteen. He isn’t overpowering, but he thrives on consistency. I was a student of Osteen. I learned a lot from him, about setting up different hitters and watching how he would take away the power from big hitters.”

Funny, I’ve never known a guy named “Claude” and I never knew he saves the Dodgers ass in that WS. Cool stuff.

Steve mentioned never hearing about the “must pitch in the majors” clause. I could be wrong, but I believe Todd Van poppel had something similar to that in his contract.

Here’s a Dodgers story you might appreciate, Gary:

After utility player Bobby Valentine was dealt by the Dodgers to the Angels, he said to The Sporting News, “When I was with the Dodgers, all of our pitchers used to put sandpaper on the ball and the umps did nothing about it.” When asked about Valentine’s comment, Claude Osteen replied to The Sporting News that a pitcher doesn’t need sandpaper to get the job done at Dodger Stadium. “With the crushed red brick infield and warning track, all the ball has to do is roll across it once and it comes back to you scratched up,” Osteen said. “I’ll admit there were times when I’d have an infielder roll it around intentionally. I know how to make the ball do tricks, and when I’d get one that was all scuffed up, I wasn’t about to throw it out of play.”

Todd Van Poppel could have used some tricks, or, better yet, learned to be a pitcher instead of a thrower. Van Poppel was 19 when he debuted with the A’s against the White Sox. He did have an eye-popping first three innings, striking out the likes of Tim Raines, Frank Thomas and Carlton Fisk, but then the proverbial roof caved in: https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1991/B09110OAK1991.htm

Willie Wilson scored the winning run in the 10th inning on a Canseco SF. The weird thing is that Rickey Henderson was walked intentionally ahead of Canseco and then a pinch runner named Brad Komminsk was inserted. I really don’t remember Komminsk or Henderson EVER being pinch run for. Bizarro world.

Komminsk actually had over 300 AB’s two years in a row but had an OPS of .592 and .640. He was, essentially, utterly worthless.

Good catch on your part, Gary, to notice that Brad Komminsk was a pinch-runner for Rickey Henderson in the Todd Van Poppel debut game on Sept. 11, 1991. The reason: The A’s said Henderson had an aching left hamstring muscle, according to the San Francisco Examiner. From Sept. 9 through Sept. 19, Henderson did not start a game, making a few pinch-hitter appearances in that time. “Although Rickey is walking without a discernible problem, manager Tony La Russa is convinced the injury is legitimate and his player is not malingering,” the Examiner noted. Reggie Jackson, with the A’s as a part-time coach, said to the newspaper, “He (Henderson) is unhappy. He’s mentally unhappy. I do think he does have physical ailments. I do think his ailments to his legs would be the same as Jose Canseco with his back. Canseco’s back is his whole game because his is a power game. Rickey’s legs are his game.”

I’m trying to find a Claude Osteen connection somewhere in all this, pal, so here’s one: Reggie had four hits and a walk in eight career plate appearances versus Osteen. That’s a .625 on-base percentage.

By the way, Brad Komminsk had been a heralded prospect with the Braves and was timed by them in 4.1 seconds going to first base from the righthanded batter’s box. At spring training in 1982, Braves farm director Hank Aaron said of Komminsk, “He could do things in this game that no one else has ever done.” Braves general manager John Mullen added, “He’s too good to be true. He has so much talent, it scares me.”

A great career. He hung around a long time. Osteen fits the stereotypical image of a ballplayer of that era.

Yes, indeed, Ken. I like how Los Angeles Times columnist Jim Murray put it:

“Osteen is to pitching what Irving Berlin is to music, Norman Rockwell to painting or Faith Baldwin to writing. He kind of produces to order, not inspiration. His is not the stuff of genius. It’s the stuff of hard work. He’s a mechanic. He knows what he’s doing and how he does it. He learned his trade like a diamond cutter. He can do it in his sleep. He will probably never pitch a perfect game but he will never pitch a careless one.”