Wintertime and the living was easy for the frontcourt trio of Bob Pettit, Cliff Hagan and Clyde Lovellette. The high-scoring glamour boys of the NBA St. Louis Hawks were living on Easy Street. Their coach, Ed Macauley, was known as “Easy Ed.” His coaching style matched his nickname. He liked a set offense, with Pettit, Hagan and Lovellette taking most of the shots.

Easy as one, two, three.

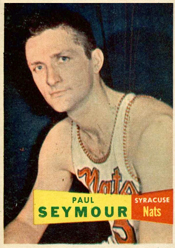

Then came a change. Paul Seymour replaced Macauley. As a playmaking guard, Seymour sparked the Syracuse Nationals to a NBA title in 1955, then became their coach. He coached like he played _ fiery, tough, wily.

Then came a change. Paul Seymour replaced Macauley. As a playmaking guard, Seymour sparked the Syracuse Nationals to a NBA title in 1955, then became their coach. He coached like he played _ fiery, tough, wily.

When Seymour came to St. Louis, he envisioned a wide-open style of play. He wanted a fast pace and scoring from the guards.

Cleo Hill was the kind of player Seymour had in mind. Hill was exceptionally quick, an acrobat who could score from anywhere on the court. After the Hawks drafted Hill, Seymour turned the rookie loose to run the floor and put up shots.

The Big Three, Pettit, Hagan and Lovellette, did not like this. Ease off, they told their coach. Buzz off, Seymour replied.

Then all hell broke loose.

Pioneer pro

As a youth, Paul Seymour played alley basketball in his hometown of Toledo, Ohio. The matchups were two against two. He and a friend, Bob Harrison, “challenged any other pair in the city,” Seymour recalled to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. “In winter, we’d shovel the snow off the alley and play on.”

(Harrison later played nine seasons in the NBA, including two with St. Louis.)

After his freshman year at the University of Toledo, Seymour, 18, quit to join the Toledo Jeeps of the National Basketball League (NBL) in 1946. “That was a great club,” he told Lowell Reidenbaugh of The Sporting News. “I was the kid, getting $87.50 a week, and we traveled in a station wagon, often covering 500 miles a night to keep our schedule. We took turns at the wheel and you know what trick I got _ the last one, from 4 a.m. to daybreak.”

Seymour picked up the lifelong habit of smoking cigars then “because, with everyone else in the car smoking, a guy needed a smokescreen in self defense,” he told Bob Broeg of the Post-Dispatch.

The St. Louis Browns had seen Seymour play baseball and in 1947, when he was 19, he signed with them, then changed his mind rather than go to minor-league Pine Bluff, Ark., as an outfielder, the Post-Dispatch reported. Instead, he went to Baltimore of the Basketball Association of America (BAA).

After the 1948-49 season, the NBL and the BAA merged to become the National Basketball Association (NBA). Baltimore sold Seymour’s contract to Syracuse for $1, according to the Toledo Blade.

Seymour played 11 seasons for Syracuse, including the last four as player-coach. He was talented and successful in both roles.

A three-time all-star, Seymour was team captain of the 1955 NBA champions, averaging 14.6 points and 6.7 assists per game. “He played a brand of defense that bordered on stalking, refusing to let his opponent out of sight,” wrote Syracuse Post-Standard columnist David Ramsey. “He dropped 25-foot set shots and sank layups with either hand. He ran the team’s offense with wisdom and imagination. In short, he could play.”

As Syracuse forward Dolph Schayes noted to the newspaper, “He was the heart and soul of the Syracuse Nats … We were scrappy and never gave up. That was Paul … He was indestructible.”

Syracuse was 155-124 in Seymour’s four seasons as coach and twice reached the NBA Eastern Division Finals. The job paid just $13,000 a year, though, and Seymour wanted better.

After the 1959-60 season, Hawks owner Ben Kerner eased Easy Ed Macauley out of the coaching job, named him general manager and wooed Seymour with a three-year contract that included a pay raise, plus incentive clauses.

“He’s a complete coach,” Kerner told The Sporting News. “He knows the game, knows the talent and has that tremendous desire which is so necessary for all champions … He’s a rough, tough competitor … He reflects confidence in his every move and that assurance rubs off on his players.”

Changing times

Ben Kerner was to Hawks basketball coaches what George Steinbrenner later became to Yankees baseball managers: a carnivore who ate them for breakfast, lunch and dinner.

In the five seasons since moving the Hawks from Milwaukee to St. Louis in 1955, Kerner went through five head coaches: Red Holzman, Slater Martin, Alex Hannum, Andy Phillip and Ed Macauley. After Hannum led the Hawks to the 1958 NBA championship, he quit. “I never liked Hannum,” Kerner told Sports Illustrated. “He was a real tough hombre … He did a hell of a job, but he never was my type of guy … I didn’t feel safe with him. He wasn’t loyal.”

(Hannum won another NBA title with the 1966-67 Philadelphia 76ers.)

As for Macauley, Kerner told Sports Illustrated’s Gilbert Rogin, “I like Macauley … but he didn’t have the guts … I do feel Paul is a better coach than Macauley.”

The team Seymour inherited was a good one. The Hawks finished in first place in the Western Division in each of Macauley’s two seasons as coach and reached the NBA Finals in 1960. Seymour was hired to win a NBA title.

In addition to the Big Three of Pettit, Hagan and Lovellette, Seymour’s 1960-61 Hawks had a self-assured rookie guard, Lenny Wilkens. (Wilkens, elected to the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame for his success as a player and a coach, was accepted by the Big Three because he passed the ball to them often. The rookie averaged 11.7 points per game.) “Our front line has the power,” Seymour told the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, “but we can increase that power through a more effective backcourt, especially in scoring.”

Seymour sent a message to the Big Three early in the 1960-61 season that the easy living days of Easy Ed were gone. (Macauley quit as general manager in September 1960.) Seymour fined Lovellette for lagging on defense during a game. As Bob Broeg noted, “When he put the bit on (Lovellette), he served notice to the rest of the team. Paul has been around long enough to know that hustle is part condition, part ability, but mostly desire.”

Described by Hawks radio broadcaster Buddy Blattner as “a backroom brawler with polish,” Seymour energized the Hawks, who hustled their way to the 1961 NBA Finals but then lost in five games to the Boston Celtics.

Boston was the better balanced team. It had plenty of muscle up front with center Bill Russell and power forward Tommy Heinsohn, and an array of guards (Bob Cousy, K.C. Jones, Sam Jones, Frank Ramsey, Bill Sharman) who poured in points. While Hagan and Pettit scored big, the Hawks’ backcourt didn’t match Boston’s. Wilkens was the only threat.

Meanwhile, two of the Hawks’ Western Division rivals had introduced big-scoring rookie guards _ Oscar Robertson with the Cincinnati Royals and Jerry West with the Los Angeles Lakers. If the Hawks were to stay atop the division and have a chance to dethrone Boston for the NBA title, Seymour determined, they’d need more firepower in the backcourt.

Urban legend

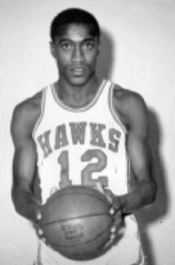

The Hawks’ first-round choice in the 1961 draft was Cleo Hill, a 6-foot-1 guard from Winston-Salem Teachers College.

Hill’s path to the NBA had been filled with roadblocks. Growing up on Belmont Avenue in Newark, N.J., “I got in with a tough bunch of guys and wasted a lot of time,” Hill said to Dave Klein of the Newark Star-Ledger. “I didn’t study, I didn’t have respect for my elders, and I thought I knew everything there was to know.”

Hill’s path to the NBA had been filled with roadblocks. Growing up on Belmont Avenue in Newark, N.J., “I got in with a tough bunch of guys and wasted a lot of time,” Hill said to Dave Klein of the Newark Star-Ledger. “I didn’t study, I didn’t have respect for my elders, and I thought I knew everything there was to know.”

The first mentor who helped Hill get on track was Frank Ceres, a coach and playground instructor at Grover Cleveland Elementary School in Newark. Ceres told Hill he could become a good basketball player. He taught Hill to shoot a jump shot and how to produce backspin.

At Newark’s South Side High School (now Malcolm X Shabazz High School), Hill came under the guidance of Frank Delany, who taught U.S. history and coached the basketball team. “The best part of the (basketball) practice was his talk period,” Hill said to the Newark Star-Ledger. “He’d talk about the educational, athletic and social aspects of his players’ lives.”

Hill became a prolific prep scorer. His homecourt gym was small, with a low ceiling that intimidated visiting players. Hill tailored his shot-making to fit the territory. His arsenal included a line-drive hook shot he could make with either hand.

Al Attles, whose success in the NBA as a player, coach and executive earned him election to the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame, played for Weequahic High School in Newark and was matched against Hill. “Cleo was the greatest high school player I’ve ever seen,” Attles said to the Star-Ledger. “In terms of overall basketball talent, he’s as good as there ever was.”

Weequahic coach Les Fein told the newspaper that Hill “could shoot from anywhere … He was incredibly quick and flexible and he had the ability to get free for any shot he wanted, any time he wanted.”

Despite Hill’s basketball talent, going to college was not a slam dunk. His academic grades “were barely passing,” the Star-Ledger noted. Frank Ceres, the elementary school mentor, made some calls to friends at Winston-Salem Teachers College. The school offered a basketball scholarship on one condition: Hill would need to get good grades in college to stay eligible.

Big man on campus

Winston-Salem Teachers College (now Winston-Salem State University) was the first historically black institution in the nation to grant degrees for teaching the elementary grades.

The school’s basketball coach, Clarence “Big House” Gaines, was dedicated to education as well as to athletics, and he helped Hill focus on studies. “He took a guy from the streets and put him into the programs _ English, mathematics and reading, remedials,” Hill recalled to the Star-Ledger. “He made me work hard and stressed getting a degree over and against making pro.”

To help Hill expand his vocabulary, Gaines encouraged a game: When Hill learned a new word, he’d test Gaines on whether the coach knew the meaning. Hill kept coming back with new words, hoping to trip up Gaines.

Hill also met a student, Eliza Ann, who emphasized to him the importance of an education. She became his wife.

(In spring 1962, after his season with the Hawks, Hill returned to Winston-Salem and completed the work to earn his degree.)

Meanwhile, Hill’s basketball skills blossomed. “He was the most scientific player I ever coached,” Gaines told the Star-Ledger. “He had the greatest assortment of shots of any player I ever coached.”

Basketball broadcaster Billy Packer was a player at a bigger Winston-Salem school, Wake Forest of the Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC), at the time Hill was in college. ACC basketball teams hadn’t integrated _ (the first black basketball player in the ACC wouldn’t arrive until December 1965) _ but Packer and his teammates would play pickup games against Hill and his teammates. “Cleo was better than anybody in the ACC at that time,” Packer told the Winston-Salem Journal.

Hill scored 2,488 career points in college. That was the school record until Earl “The Pearl” Monroe totaled 2,935. (Both achieved those figures before there was a three-point line.) Though Gaines coached both players, he told Mary Garber of the Winston-Salem Journal in 1973 that Hill was “the most complete player I’ve ever had … He could do the job both offensively and defensively.”

Special talent

The Hawks took Hill with the eighth pick in the first round of the March 1961 NBA draft. Paul Seymour, chief scout Emil Barboni and scouting adviser Ed Vogel saw Hill play and put him at the top of their list. “He would have been our first draft choice even if we would have had the first pick,” Seymour told the Post-Dispatch.

The Celtics, selecting after St. Louis, would have taken Hill if the Hawks hadn’t, the Post-Dispatch reported.

Marty Blake, then the Hawks’ business manager, later told reporter Vahe Gregorian that Hill “came into the league with abilities that were 40 years ahead of his time.”

“Great first step, unlimited range … and he was quick,” Blake said to the Asbury Park (N.J.) Press. “I mean, he was a speed demon.”

In a 1993 interview with reporter Bill Handleman about Hill, Billy Packer said, “There was no question he was destined for superstardom in the NBA. We’re not talking about some nice rookie here. We’re talking about Michael (Jordan). Cleo was Michael 33 years ago. At 6-foot-1, he did the things Michael Jordan does … We’re talking about a guy who should be in the (Naismith) Hall of Fame.”

Packer’s broadcast colleague Bill Raftery concurred, telling the Asbury Park Press in 1993 that Hill “did a lot of Jordanesque type of things we see today.”

With Lenny Wilkens unavailable for the first three months of the 1961-62 NBA season because of a military service commitment, Hill became the Hawks’ top guard. Seymour worked with the rookie to get him ready.

Power plays

In the regular-season opener, at home against Cincinnati, Hill scored 26, “drawing roars from the large crowd with his spectacular leaps while driving for shots or snaring rebounds,” the Post-Dispatch reported.

The black-owned weekly, St. Louis Argus, noted, “This young man captures the imagination of the crowd with his grasshopper leaps under the basket (and) his showboating gallops down (the) court.” Game stats

Hill scored 16 in his second game, but went cold soon after. The rookie missed 13 of 16 against Syracuse, misfired on 10 of 12 versus Chicago and clanked another 13 of 16 against Syracuse again.

Critics said he looked nervous, insecure, and there were grumbles about his unorthodox ways and playground style.

Seymour asked his players for patience and unity. He was confident Hill would figure it out, make the necessary adjustments.

The way the Big Three saw it, though, the rookie wasn’t ready, he’d been given too big a role too soon, and he should stop shooting so much. From their perspective, the team was better when the offense revolved around them.

Tensions built to a boiling point. In late October, Seymour told the Post-Dispatch that Lovellette “has been pouting for a month” and has complained about “not getting the ball.” Seymour also said one of the Big Three came to him and said Hill was getting too much publicity and should be benched.

“Never before was it more obvious that we needed a fast backcourt man, an outside scorer like Hill, an exceptional talent, but the big guys up front wouldn’t play with him,” Seymour told Bob Broeg of the Post-Dispatch. “Jealous, no doubt. Protecting those big salaries, I guess. Imagine, telling me the kid was getting too much publicity.”

On Nov. 8, Hill scored 20 points and snared 12 rebounds against the Lakers. He made half his shots the next game, finishing with 16 against Detroit. Then he sank six of nine and totaled 16 points versus Cincinnati.

It appeared Hill was finding a groove, but Ben Kerner, acting on behalf of the Big Three, ordered Seymour to remove the rookie from the starting lineup.

Reluctantly, Seymour did so, but he was seething.

Speaking at a luncheon in Detroit, before the Hawks played the Pistons, Seymour told the audience, “I’d trade any of our top players and that includes Bob Pettit … There are no untouchables any more on my club.”

Two days later, Nov. 17, 1961, with the Hawks’ record at 5-9, Kerner fired Seymour. “I couldn’t run a smooth club with the bad feeling between team and coach,” Kerner told the Globe-Democrat.

Seymour said he was fired because he insisted, against the wishes of the Big Three, to start Hill. “I’d just rather lose my job doing what I think is right,” Seymour said to the Globe-Democrat.

Regarding the Big Three, he told the newspaper, “They didn’t help the kid but were against him. That’s my only gripe, the way they boycotted the kid … It takes the heart out of you when your own team players won’t help you … I wouldn’t treat a dog the way they treated him.”

Hill’s take on the Big Three was, “They knew they were getting paid for the points they scored, and, here I was, taking their points … It wasn’t racial. It was points,” he told the Newark Star-Ledger.

Pettit said to the Associated Press, “There’s nothing we want more than for Cleo Hill to be the greatest ballplayer in the world. We don’t care who plays or who scores as long as we win. I know I speak for Cliff (Hagan) and Clyde (Lovellette).”

New directions

Kerner asked Pettit to fill in as interim coach until a replacement for Seymour could be hired. In Pettit’s first game in that role, Hill played a total of two minutes.

Fuzzy Levane, who’d coached the Hawks when they were based in Milwaukee, took over for the remainder of the season and used Hill sparingly. The Hawks finished 29-51. Hill averaged 5.5 points in 58 games during his only NBA season.

Harry Gallatin became the next Hawks coach, and he cut Hill from the roster before the 1962-63 season. No other NBA team was interested in him.

Hill went on to play in the lower levels of professional basketball with the Philadelphia Tapers of the American Basketball League and then the Trenton Colonials, New Haven Elms and Scranton Miners of the Eastern League.

Putting his college degree to use, Hill became an elementary school teacher in New Jersey and then the basketball coach at Essex County College in Newark. His record in 24 seasons there was 489-128.

Back home in Syracuse, Paul Seymour worked in real estate, owned a liquor store and coached basketball at Onondaga Community College from 1962-64. He returned to the NBA as coach of Baltimore (1965-66) and Detroit (1968-69).

In a letter he sent to Hill, Seymour wrote, “Occasionally, I get disgusted thinking what happened to you (in the NBA). I believe you got white-balled.”

Great story. A tale of egos and racism. Can’t get the image out of my head of the Toledo Jeeps riding high in a smoke-filled station wagon on their way to the next game. No word on whether they at least rolled down the windows?

Thanks, Ken. You summarized it well.

I’m so glad you appreciated the part about the 1946 Toledo Jeeps in the smoke-filled station wagon. No word on whether the windows were rolled down, but it was fun to research that vehicle. The 1946 Willys Jeep Station Wagon was an all-steel vehicle, America’s first of its kind, offering a durable, low-maintenance alternative to traditional woodie wagons. It had a distinctive flat grille and styling that mimicked wood, powered by the L-134 Go-Devil engine, and setting the stage for the modern SUV with innovations such as independent front suspension and a functional tailgate.

They probably had to bring that tank in for gas every hundred miles or so.

Good to see some NBA on your blog, Mark.

Thanks, Gary. I was fortunate to grow up as a fan of 1960s NBA. My favorite team was the Knicks. In the playground courts, I would practice imitating the shooting styles of Dave DeBusschere, Bill Bradley, Willis Reed, Dick Barnett and Walt Frazier.

A little before my time…I didn’t become a die hard fan until about 1986, and my favorite player (still is) was Magic Johnson. I don’t watch the game much anymore. The lack of hand checks, defense and the mindless chucking of 3 pointers makes it practically unwatchable.

Agree completely.

What a fascinating and frustrating story of what if.

I got a kick imagining Seymour as a kid traveling around in that station wagon and him getting the graveyard shift behind the wheel and then later on, him succeeding as a player coach.

The mentioning of Dolph Schayes brought back great memories of his son Danny Schayes when he played on the Bucks. I guess it musta been my dad that told me about Dolph being the first player to reach 10,000 points, but I just looked it up to verify and wikipedia says he was the first to reach 15,000 points and 10,000 rebounds as well.

I love the way you put this – “Ben Kerner was to Hawks basketball coaches what George Steinbrenner later became to Yankees baseball managers: a carnivore who ate them for breakfast, lunch and dinner.”

There’s so much to love about Hill’s basketball skills and also what he said about Frank Delaney…..musta been one great human being like Hill sounds too. I really enjoyed this.

I enjoyed your observations, Steve. I’m delighted you knew about Dolph Schayes and took the time to look up his stats and share those here. In 1963, Danny Biasone sold the Syracuse Nationals to Ike Richman and Irv Kosloff, who relocated the franchise to Philadelphia and changed the name to 76ers. The 76ers replaced the Philadelphia Warriors, who relocated to San Francisco after the 1961-62 season.

Yes, indeed, Cleo Hill was fortunate to have mentors such as Frank Ceres, Frank Delany and Clarence Gaines. It’s heartening that, after his playing career, Hill paid it forward by being a teacher, coach and mentor. First, he was a teacher by day at Lincoln Elementary School in East Orange, N.J., and a recreation teacher at night. Then came the coaching stint at Essex County College.

In 1982, Hill told the Newark Star-Ledger, “I came away from pro basketball with nothing. They didn’t pay that much. If (Clarence) Gaines hadn’t insisted that his players get an education and a degree, I wouldn’t be teaching and coaching at Essex County College today.”

Another excellent post on the St.Louis Hawks. It doesn’t surprise me that Paul Seymour preferred a more fast paced offense. The year that the Syracuse Nats one the NBA Championship was the first season that the NBA implemented the 24 second shot clock. It wouldn’t surprise me if those alley pickup games he played as a youth had an influence on him as well. It’s a darn shame that Cleo Hill’s NBA career went the way it did. I find it also strange that no other NBA was willing to take a chance on him. His coaching legacy however not only vindicated him but also proved everyone else that they were wrong on giving up on him too soon. Just one last thing. Paul Seymour would be proven right that the Hawks lacked depth. While they still remained a good team during the 60’s they couldn’t match the overall depth of the Celtics and Lakers.

I appreciate all of your smart insights, Phillip.

To your point:

In his first training camp with the Hawks in September 1960, Paul Seymour told the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, “With the rebounding power they had, they should have been running a lot more.”

After Seymour was fired in November 1961, he said to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, “The Hawks must get some scoring from the backline, or they won’t win very often. Other clubs know that the big men won’t give up the ball, so they double-team the Hawks and get away with it.”

Bob Burnes of the Globe-Democrat noted, “The opposing teams still play 5 on 3 against the Hawks’ front court.”

To your point:

Burnes also wrote after Paul Seymour’s firing in November 1961, “Cleo Hill, a tremendously talented athlete but at the moment a confused and almost frightened kid, is the innocent pawn in the whole thing.”

In 2008, Brad Parks of the Newark Star-Ledger concluded, “He could have been one of the greatest players in NBA history were it not for some incalculable combination of jealousy, poor timing and skin color.”

Seymour told the Winston-Salem Journal “it is strange no one took Cleo” after the Hawks released him.

Seymour also said to the Asbury Park Press, “The grapevine was the Big Three sort of blackballed him, or white-balled him, as the case may be.”

These guys were before my time, Mark, but of course I learned a good bit about them growing up…as well as here today. (FYI I liked seeing Billy Packer noted here – my mother served as one of the producers of ACC Basketball telecasts years ago, and I even had breakfast with Billy on one occasion. One of the more authentic and real people I ever met among television folk) The stories behind the scenes with all of the players featured here were interesting and informative.

Thanks, Bruce. Wow! What a fascinating job your mother had. I am delighted to learn Billy Packer impressed you. My father, a first generation Polish-American, always was proud of what Billy Packer (born Anthony William Paczkowski) achieved in sports and in broadcasting.