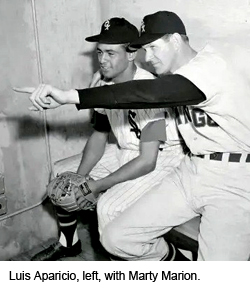

On his way to becoming the first Venezuelan to get elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, shortstop Luis Aparicio received a big early boost from a former Cardinals standout at the position.

Marty Marion was the White Sox manager who brought Aparicio to the major leagues and made him the starting shortstop as a rookie in 1956.

Marty Marion was the White Sox manager who brought Aparicio to the major leagues and made him the starting shortstop as a rookie in 1956.

Nicknamed “Mr. Shortstop,” Marion was the starter on four Cardinals pennant winners in the 1940s and the first shortstop to win the National League Most Valuable Player Award.

Aparicio merely had two years of minor-league experience when Marion picked him to be the White Sox shortstop. It was an astute decision. Aparicio won the American League Rookie of the Year Award and went on to have a stellar career. He earned the Gold Glove Award nine times, led the American League in stolen bases for nine years in a row (1956-64) and totaled 2,677 hits. Video

Elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1984, Aparicio is one of several Venezuelans who have achieved prominence in the big leagues. Others (in alphabetical order) include Bobby Abreu, Ronald Acuna Jr., Jose Altuve, Miguel Cabrera, Dave Concepcion, Andres Galarraga, Freddy Garcia, Ozzie Guillen, Felix Hernandez, Magglio Ordonez, Salvador Perez, Johan Santana, Manny Trillo, Omar Vizquel and Carlos Zambrano.

The first Venezuelan to play in the majors was pitcher Alex Carrasquel with the 1939 Washington Senators. The first Venezuelan to play for the Cardinals was outfielder Vic Davalillo in 1969. Besides Davalillo and Andres Galarraga, other Venezuelans who were noteworthy Cardinals included Miguel Cairo, Willson Contreras, Cesar Izturis, Jose Martinez and Edward Mujica.

Baseball genes

Aparicio was from the seaport city of Maracaibo in northwestern Venezuela. According to the encyclopedia Britannica, “Until petroleum was discovered in 1917, the city was a small coffee port. Within a decade it became the oil metropolis of Venezuela and South America. It has remained a city of contrasts _ old Spanish culture and modern business, ancient Indian folklore and distinctive modern architecture.”

Aparicio’s father (also named Luis) was a standout shortstop in Latin America and was known as “El Grande,” the great one. When the father retired as a player during a ballpark ceremony in 1953, he handed his glove to his 19-year-old son and they embraced amid tears.

While playing winter baseball in Venezuela for Caracas, young Luis Aparicio got the attention of White Sox general manager Frank Lane and scout Harry Postove. Cleveland Indians coach Red Kress also was in pursuit of the prospect. After the White Sox paid $6,000 to Caracas team president Pablo Morales, Aparicio signed with the White Sox for $4,000, The Sporting News reported.

The White Sox sent Aparicio, 20, to Waterloo, Iowa, in 1954. The Waterloo White Hawks were a Class B farm club managed by former catcher Wally Millies. Aparicio “couldn’t speak a word of English,” according to Arthur Daley of the New York Times, but language was no barrier to his ability to play in the minors. Before a double hernia ended his season in July, he produced 110 hits in 94 games for Waterloo and had 20 stolen bases. Wally Millies filed a glowing report to the White Sox: “Aparicio has an excellent chance to make the big leagues.”

On the rise

Returning to Venezuela for the winter, Aparicio hired a tutor and learned English. The White Sox invited him to their 1955 spring training camp. That’s when Marty Marion got a look at him.

After managing the Cardinals (1951) and Browns (1952-53), Marion was a White Sox coach in 1954. He became their manager in September 1954 after Paul Richards left to join the Orioles.

Marion liked what he saw of Aparicio at 1955 spring training and it was he who suggested the shortstop skip the Class A level of the minors and open the season with the Class AA Memphis Chickasaws.

Aparicio responded to the challenge, totaling 154 hits and 48 steals. He dazzled with his range and throwing arm. David Bloom of the Memphis Commercial Appeal deemed Aparicio “worth the price of admission as a single attraction.”

Memphis had two managers in 1955. Jack Cassini, who was the second baseman and manager, had to step down in early August after being hit in the face by a pitch. Retired Hall of Fame pitcher Ted Lyons, the White Sox’s career leader in wins (260), replaced Cassini. Both praised Aparicio in reports to the White Sox.

Cassini: “He does everything well.”

Lyons: “Aparicio plays major league shortstop right now … Can’t miss.”

Lyons, who played 21 seasons in the majors and spent another nine there as a manager and coach, told The Sporting News, “The kid’s quick as a flash and has a remarkable throwing arm. He’s dead sure on a ground ball and makes the double play as if it were the most natural thing in the world. He’s one of the greatest fielding shortstops I have ever seen.”

Ready and able

Based on the reports he got on Aparicio during the summer following his firsthand observations in spring training, Marion urged the White Sox front office to trade shortstop Chico Carrasquel so that Aparicio could step into the job in 1956. Carrasquel was sent to Cleveland for outfielder Larry Doby in October 1955.

The move was bold and risky. A Venezuelan and nephew of Alex Carrasquel, Chico Carrasquel was an American League all-star in four of his six seasons with the White Sox, and the first Latin American to play and start in an All-Star Game.

Marion and others, however, became disenchanted with Carrasquel’s increasingly limited fielding range. “I was amazed when I watched Carrasquel (in 1955),” White Sox player personnel executive John Rigney told The Sporting News. “He had slowed up so much he didn’t look like the same player.”

Marion said to reporter John C. Hoffman in January 1956, “I know Luis Aparicio is a better shortstop right now than Carrasquel was last year … I saw enough of him last spring during training to know he’s quicker than Chico and a better hustler.”

Aparicio showed at 1956 spring training he was ready for the job. As Arthur Daley noted in the New York Times, Aparicio “has extraordinary reflexes as well as the speed afoot to give him the widest possible range. He breaks fast for a ball and his hands move with such lightning rapidity that his glove smothers the hops before they have a chance to bounce bad. He gets the ball away swiftly to set up double plays and ranks as probably the slickest shortstop in the business.”

Marion was impressed by all facets of Aparicio’s game and his ability to mesh with second baseman Nellie Fox. (Aparicio and his wife Sonia later named a son Nelson in honor of Fox.)

“I’m certain now that he’ll be twice the shortstop that Carrasquel was last year,” Marion told The Sporting News in March 1956.

Rookie sensation

Marion considered putting Aparicio in the leadoff spot, but instead batted him eighth. “He has all the physical equipment for becoming a wonderful leadoff man, but at the moment he still lacks the ability to draw walks,” Marion explained to The Sporting News. “Once he gets that, he’ll be one of the best. Drawing walks is something that comes with experience. He has to sharpen his knowledge of the strike zone and then develop the confidence to lay off those pitches that are just an inch or two off the plate.”

Once the season got under way, the rest of the American League joined Marion in voicing their admiration of the rookie. Aparicio played especially well versus the powerhouse Yankees. He hit .316 against them, including .395 in 11 games at Yankee Stadium, and fielded superbly.

“He is not only the best rookie in the league; we’d have to say he was the best shortstop,” Yankees manager Casey Stengel exclaimed to the Chicago Tribune.

Yankees shortstop Phil Rizzuto, in the final season of a Hall of Fame career, said to The Sporting News, “As a fielding shortstop, Aparicio is the best I ever saw.”

Rizzuto said Aparicio’s superior range reminded him of Marty Marion with the Cardinals. Marion, though, told The Sporting News, “He has to be better than I was. He covers twice the ground that I did.”

In August 1956, Marion moved Aparicio to the leadoff spot. Aparicio batted .291 there in 31 games, with a respectable .345 on-base percentage. “We frankly didn’t think he would come along quite this fast,” Marion told the Chicago Tribune.

Aparicio completed his rookie season with 142 hits and 21 stolen bases. He batted .295 with runners in scoring position and .412 with the bases loaded. He made 35 errors, but also led the league’s shortstops in assists and putouts.

Changing times

The 1956 White Sox finished in third place at 85-69, 12 games behind the champion Yankees. On Oct. 25, White Sox vice-president Chuck Comiskey summoned Marion to a meeting. When it ended, Marion no longer was manager.

“The White Sox called it a resignation and Marty, always agreeable, went along with this label,” Edward Prell of the Chicago Tribune noted. “Marion’s official statement of resignation, however, sounded like one of those Russian confessions,” departing “in the best interest of the club.”

According to the Tribune, “It was known that Marion’s insistence on keeping Aparicio eighth in the batting order did not set well with some of the White Sox officials. They thought Marty should be … having him lead off.”

Days later, the White Sox hired Al Lopez, who led Cleveland to a pennant and five second-place finishes in six years as manager. In the book “We Played the Game,” White Sox pitcher Billy Pierce said Marion “did a very good job with us. I didn’t know why he didn’t stay with us longer, other than that Al Lopez was available.”

Marion never managed again.

With Aparicio the centerpiece of a team that featured speed, defense and pitching, Lopez led the White Sox to the 1959 pennant, their first in 40 years.

Traded to the Orioles in January 1963, Aparicio joined third baseman Brooks Robinson in forming an iron-clad left side of the infield. In “We Played the Game,” Robinson said, “Luis was just a sensational player … He was the era’s best-fielding shortstop. He had so much range that I could cheat more to the (third-base) line.”

With their pitching and defense limiting the Dodgers to two runs in four games, the Orioles swept the 1966 World Series.

Aparicio was traded back to the White Sox in November 1967. He spent his last three seasons with the Red Sox.

Tradition of excellence

When Ozzie Guillen was a boy in Venezuela, he idolized Luis Aparicio. Guillen became a shortstop. In 1985, he reached the majors with the White Sox and won the American League Rookie of the Year Award. He eventually became an all-star and earned a Gold Glove Award, too.

In 2005, as White Sox manager, Guillen led them to their first pennant since the 1959 team did it with Aparicio. Before Game 1 of the World Series at Chicago against the Astros, Guillen got behind the plate and caught the ceremonial first pitch from Aparicio.

The White Sox went on to sweep the Astros, winning their first World Series title since 1917.

I like that continuity and generational scene before game 1 of the 2005 series – Aparicio first pitch to Guillen. An excellent idea I think. Easy to hear an elder sharing the history with a junior..

That he, Aparicio couldn’t speak a word in english and that he studied the language reminds me of the movie SUGAR, a cautionary tale about players from central and south america who don’t make it and find themselves kind of stuck in america. no more spoilers.

When Aparicio’s father retired and he gave his son his mitt and the tears….such a special moment. I wonder if Luis used the mitt?

I wonder how the defensive metrics rate Aparicio? The praise from coaches and managers is incredible, of him being the greatest shortstop that they’d ever seen. I’m gonna do a deep dive on you tube to see him in action with the GO GO sox of 59….a great time to be in the midwest….Braves in 57, almost in 58 and sox in 59.

I’m glad you appreciate the passing of the torch, or, in this case, the glove, from senior Luis Aparicio to his son and then from him to Ozzie Guillen.

An anecdote: In a 1960 game, Whitey Herzog of the Orioles sliced a humpback fly ball down the left field line. Left fielder Minnie Minoso, who had been playing Herzog, a left-handed batter, to pull had no chance to reach the ball. Aparicio raced full speed from where he had been playing near the second-base bag, reached out with his bare hand and snagged the ball. “Best catch I ever made,” Aparicio told the Associated Press.

this might be a stupid question, but what’s a humpback fly ball?

Same as a dying quail, a softly hit, looping fly ball that falls rapidly.

what a great expression – a dying quail. i’ve never seen one before or maybe i have and didn’t know it was a quail? i’ve seen some birds smash into windows. I guess that would be more like a collision at the plate, but those aren’t allowed anymore.

Chico Carrasquel was indeed a good shortstop but Marty Marion knew that in Luis Aparicio he had a great shortstop. It’s pretty cool that not only did Carrasquel tutor Aparicio when he first came up but also that years later Aparicio paid tribute to Chico Carrasquel. I also appreciated the fact that Luis brought back the lost art of stealing bases. I’ve got to say though that I didn’t know until now just how valuable he was to that 1966 Orioles team. I would have never guessed that he led them in hits. I also noticed that during his second stint with the White Sox he was their hits leader for three consecutive years. Not bad for a player in the twilight of his career.

Thanks for all the information, Phillip.

One more tidbit: Though Luis Aparicio was not a power hitter, his home run history is intriguing. He hit his first home run against Tommy Lasorda and his last versus Jim Palmer. Aparicio also slugged homers against the likes of Whitey Ford, Denny McLain, Mickey Lolich, Luis Tiant and Sam McDowell.

i love finding out that hall of famers had their troubles with certain batters. Thanks Mark.

Why in the world would anybody, ever, under any circumstances, trade Luis Aparicio? Brilliant player.

According to the Chicago Tribune, when the White Sox traded Luis Aparicio and outfielder Al Smith to the Orioles for pitcher Hoyt Wilhelm, shortstop Ron Hansen, third baseman Pete Ward and outfielder Dave Nicholson on Jan. 14, 1963, “Many South Side fans, calling the Tribune to inquire if they had heard right, were shocked by the swapping of the 29-year-old Venezuelan.”

Aparicio had balked when the White Sox sent him a contract calling for a $5,000 pay cut. Aparicio was quoted at the time as saying, “It will be 40 years before the White Sox win another pennant.”

Indeed, 42 years after he made his remark, the White Sox finally won a pennant.

Marty Marion was ahead of his time, both in being a 6′-2″ shortstop and in encouraging Aparicio to draw more walks before he could be a leadoff hitter; Luis never really got the hang of that as his .313 career OBP attests.

While Aparicio likely was superior to Marion on defense, I think Marty sold himself a little short with his claim that Luis covered twice the ground that he did.

Man, Brooks Robinson and Luis Aparicio on the same left side of the infield. That just might be the best such defensive combo in MLB history.

I enjoyed your astute comments. You know your baseball.

You’re so right about Marty Marion being ahead of his time for the reasons you cite. Frank Lane was the White Sox general manager who hired Marion. Lane left for the Cardinals after the 1955 season and hired Fred Hutchinson as manager, but he remained a Marty Marion fan. According to the Chicago Tribune, Lane explored the possibility of a swap of Hutchinson for Marion.

I’d love to be a pitcher and have Luis Aparicio and Brooks Robinson working the left side of the infield. As Lou Hatter of the Baltimore Sun wrote in 1963, “Aparicio and Robinson monopolize their share of the Orioles infield like General Motors.”