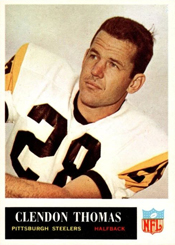

As a college football player, Clendon Thomas scored touchdowns in bunches. As a NFL player, his primary job was to prevent touchdowns.

In three varsity seasons (1955-57) with Oklahoma, Thomas scored 36 touchdowns: 34 (rushing or receiving) as a running back, one as a punt returner and the other on an interception return as a defensive back.

In three varsity seasons (1955-57) with Oklahoma, Thomas scored 36 touchdowns: 34 (rushing or receiving) as a running back, one as a punt returner and the other on an interception return as a defensive back.

In 11 years with the Los Angeles Rams (1958-61) and Pittsburgh Steelers (1962-68), Thomas had stints on offense as a receiver and a kick returner, but he primarily was a cornerback and a safety. He intercepted 27 passes and recovered 10 fumbles, returning one for a touchdown.

Some of Thomas’ best NFL performances came versus the St. Louis Cardinals.

Elected to the College Football Hall of Fame in 2011, Thomas was 90 when he died on Jan. 26, 2026.

Producing points

In his hometown of Oklahoma City, Thomas grew up in a neighborhood populated primarily with oil field workers.

At Southeast High School (also the alma mater of baseball players Bobby Murcer, Darrell Porter and Mickey Tettleton), Thomas played football but “we weren’t too good,” he recalled to the Los Angeles Times.

A sportswriter convinced Oklahoma’s football staff to give Thomas a conditional scholarship. Showing speed, versatility and an ability to reach the end zone, Thomas impressed head coach Bud Wilkinson. In 1955, his sophomore year, Thomas joined junior Tommy McDonald as Oklahoma’s varsity running backs. McDonald scored 15 touchdowns and Thomas totaled nine (eight rushing and one on a punt return). The twin touchdown terrors led Oklahoma to an 11-0 record. Thomas also played defensive back. Beginning with a 20-0 victory over Missouri, Oklahoma shut out four consecutive foes and became national champions.

Thomas was college football’s leading scorer in 1956 as a junior, with 18 touchdowns (13 rushing, four receiving and one on a return of an intercepted pass from Paul Hornung of Notre Dame). Thomas averaged 7.9 yards per carry and 20.1 yards per catch. “He leans forward as he drives, his long legs knifing up and down, making him a hard man to tackle,” Deane McGowen of the New York Times observed. “Despite his long stride, he has the quickness of an open-field runner and can move laterally as well.”

The combination of Thomas and McDonald (12 TDs rushing and four receiving) carried Oklahoma to another national title in an undefeated 1956 season. Wins included 45-0 against Texas, 40-0 versus Notre Dame and 67-14 over Missouri.

Bud Wilkinson “taught me to reach down and do things I didn’t know I was capable of,” Thomas told The Daily Oklahoman. “He prepared us to win.”

Though slowed by a hip pointer his senior season in 1957, Thomas totaled nine rushing touchdowns. Oklahoma finished 10-1 for the year (Notre Dame snapped the Sooners’ 47-game win streak) and 31-1 during Thomas’ three varsity seasons. Video

Billy Vessels, the 1952 Heisman Trophy winner as an Oklahoma running back, told the Tulsa World in 1999 that Thomas “is probably the most underrated player we’ve ever had (at Oklahoma). He represented everything you wanted a college football player to be.”

L.A. days

The Los Angeles Rams took Thomas in the second round of the 1958 NFL draft, but he fractured his left ankle returning a kickoff for the college all-stars in an exhibition game against the Detroit Lions and was sidelined until November of his rookie season.

During his first three years with the Rams, Thomas was tried at halfback (“I’m a gangly kind, not the type they were looking for,” he told The Pittsburgh Press), tight end, split end and cornerback. He had some success as a receiver. In 1960, he caught a touchdown pass against the Cardinals, in their first regular-season game since moving from Chicago to St. Louis, and made seven catches for 137 yards against the Green Bay Packers.

Thomas returned fulltime to defense in 1961, starting at safety for the Rams, then was traded to the Steelers for linebacker Mike Henry in September 1962.

(Henry went on to an acting career, most notably as Tarzan in three movies from 1966-68. While filming a jungle scene, he was attacked and bitten on the face by a chimpanzee. Henry also had roles in “The Green Beret,” “Rio Lobo,” “Soylent Green,” “The Longest Yard” and “Smokey and the Bandit.”)

Multi-tasking

Thomas was the Steelers’ interceptions leader in 1962 (seven) and 1963 (eight). He picked off two Charley Johnson passes in a 1963 game versus the Cardinals.

During the 1964 season, the Steelers needed receivers, so head coach Buddy Parker asked Thomas to play both offense and defense. According to Roy McHugh of The Pittsburgh Press, Thomas, who owned horses on a ranch in Oklahoma, took a “bronco buster’s attitude” to Parker’s request. In other words: Bring it on.

“When I signed my contract,” Thomas told the newspaper, “I signed to play whatever position they picked for me.”

On Nov. 8, 1964, in his first game as a Steelers receiver, Thomas had four catches for 61 yards against the Cardinals. Consistently in the clear, Thomas would have had more receptions if quarterback Bill Nelsen had been on target. Thomas “knew what he was doing all the time,” Parker told The Pittsburgh Press, “and he ran his patterns as though he had been running them all season.”

Three weeks later, in a rematch with the Cardinals, Thomas intercepted a pass and made four catches for 113 yards.

Mike Nixon became Steelers head coach in 1965 and he continued to use Thomas as a receiver. In one of his best performances that season, Thomas had seven catches for 90 yards in a November game against St. Louis.

For his NFL career, Thomas averaged 17.4 yards per catch on 60 receptions. He also ran back kickoffs, averaging 25.1 yards on 22 returns.

However, as The Pittsburgh Press noted, “The Steelers’ defense was weaker without Thomas.” Restored fulltime to defense, Thomas finished his last three seasons at safety for Pittsburgh. “I’m glad to be back on defense,” Thomas told The Press. “I think I belong there and can help the team more.”

After his playing days, Thomas founded a chemical products company that manufactured water repellents for the construction industry.

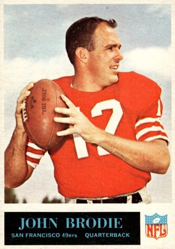

After a hospital stay for back treatment, Brodie had one of his best games as San Francisco 49ers quarterback, passing for three touchdowns in a 35-17 triumph over the Cardinals.

After a hospital stay for back treatment, Brodie had one of his best games as San Francisco 49ers quarterback, passing for three touchdowns in a 35-17 triumph over the Cardinals. He played in a World Series with the Cincinnati Reds. He was a head coach in college and pro football. He took a team to the Rose Bowl. He led the Philadelphia Eagles to two NFL championships.

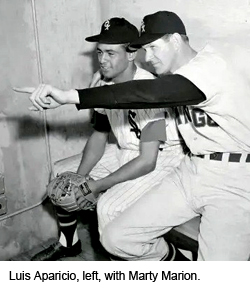

He played in a World Series with the Cincinnati Reds. He was a head coach in college and pro football. He took a team to the Rose Bowl. He led the Philadelphia Eagles to two NFL championships. Marty Marion was the White Sox manager who brought Aparicio to the major leagues and made him the starting shortstop as a rookie in 1956.

Marty Marion was the White Sox manager who brought Aparicio to the major leagues and made him the starting shortstop as a rookie in 1956. A two-time Olympic gold medalist in track and field as well as a football standout, Thorpe wasn’t as prominent in baseball. For six seasons in the National League with the Giants, Reds and Braves, he mostly was a spare outfielder.

A two-time Olympic gold medalist in track and field as well as a football standout, Thorpe wasn’t as prominent in baseball. For six seasons in the National League with the Giants, Reds and Braves, he mostly was a spare outfielder. Then, almost, there was … the St. Louis Scrambler.

Then, almost, there was … the St. Louis Scrambler.