(Updated Aug. 2, 2020)

In considering a career path for 1972, Mike Shannon could have attempted a comeback as a Cardinals player or accepted a position on manager Red Schoendienst’s coaching staff. He also could have become a minor-league manager. Instead, he became a Cardinals broadcaster.

Shannon, who helped the Cardinals win three National League pennants and two World Series titles in the 1960s as a right fielder and third baseman, had his playing career cut short in 1970 because of a kidney disease. He spent the 1971 season as the Cardinals’ assistant director of promotions and sales.

Shannon, who helped the Cardinals win three National League pennants and two World Series titles in the 1960s as a right fielder and third baseman, had his playing career cut short in 1970 because of a kidney disease. He spent the 1971 season as the Cardinals’ assistant director of promotions and sales.

In May 1971, Shannon told the Los Angeles Times-Washington Post News Service, “Ever since I’ve been working, since I was 19 years old, I’ve been in the St. Louis organization. On and off the field, I’m a Cardinal all the way. The difference now is I’m trying to sell the Cardinals off the field.”

After one season in promotions and sales, Shannon went looking for another role. According to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Shannon had bought a 350-acre cattle ranch in central Missouri and was prepared to spend his time doing that if he couldn’t get another position with the Cardinals.

In The Sporting News, columnist Dick Young reported Stan Musial told him Shannon “will try to make a comeback with the Cardinals” as a player in 1972.

A month later, The Sporting News reported “Shannon had been in the picture as a coach” for Schoendienst’s 1972 staff. Years later, Shannon told Dan Caesar of the Post-Dispatch that when he declined the coaching opportunity, “I felt really bad because jobs were really tough to get in baseball, but it just wasn’t the kind of money I needed to get by on with five kids to raise and send to college.”

According to the Post-Dispatch, Cardinals general manager Bing Devine offered Shannon the chance to become manager of the Cardinals’ 1972 Class AAA Tulsa club, replacing Warren Spahn. Shannon later confirmed he rejected the offer.

Instead, Shannon was selected in November 1971 to join Jack Buck and replace Jim Woods on the Cardinals broadcast team for 1972.

Opportunity knocks

In the book “Jack Buck: That’s a Winner,” Buck recalled the position opened for Shannon when Woods, unwilling to make promotional appearances on behalf of the Cardinals and team owner Anheuser-Busch, departed for a job with the Oakland Athletics.

“Woods became ill with a gallbladder attack shortly after he was hired (by the Cardinals), and later didn’t do the things he was expected to do by our bosses,” Buck said. “He thought Anheuser-Busch demanded too much of the broadcasters and (he) didn’t show at appearances they wanted him to make in the community, and didn’t attend luncheons and banquets.

“Woods didn’t like someone telling him he had to be here or there at a certain time, although he knew that was part of the job. He left as soon as he could.”

Swing and miss

Years later, Shannon told Mike Eisenbath of the Post-Dispatch that when he accepted the broadcasting job, “I don’t think I was looking at doing it past one year. I just figured, ‘I think I’ll try this.’ ”

Unpolished, Shannon struggled to adapt to broadcasting.

“Shannon’s delivery at first was about as jagged as a broken beer bottle,” the Post-Dispatch’s Dan Caesar wrote.

Broadcaster Jay Randolph said to the Post-Dispatch, “Shannon was raw, raw, raw. Man, he was chopped meat.” Said broadcaster Ron Jacober: “There were a lot of dissatisfied listeners. I myself wondered how in the world could they have hired this guy. He was just awful.”

Shannon knew it. In 1972, he told the Post-Dispatch, “I have a poor radio voice … I’m not the guy with the golden lungs … I’ll probably be moving out of this business into raising cattle eventually.”

Years later, reflecting on his 1972 broadcast debut, Shannon told the Evansville Courier & Press: “It was like buying a new house. I didn’t know where the bathroom was or where the garage was. I knew nothing about the mechanics.”

Shannon told the Post-Dispatch, “I didn’t become frustrated, but a lot of the listeners may have been.”

That’s a winner

Shannon credited Jack Buck with teaching him on the job.

“My real ace in the hole I had was Jack,” Shannon told the Post-Dispatch. “Good Lord of mercy, I don’t know what I would have done without him. That man helped me so much. I didn’t have to go to broadcasting school. Working with Jack was like having a private tutor on the job training.”

Buck opened his home to Shannon for training sessions.

“We’d have a tape recorder and a stopwatch, and I’d try to coach him on how to do a scoreboard show,” Buck said to the Post-Dispatch.

Shannon became a success and remained a Cardinals broadcaster for parts of six decades. His conversion to broadcasting “turned out to be pure inspiration,” the Post-Dispatch observed. “Shannon has given Cardinals fans years of expertise, laughter, malaprops, insight and frequent doses of uncommon common sense.”

He never tried to be perfect. “Perfection was hung on a cross a long time ago,” Shannon said.

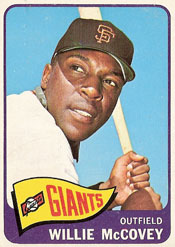

Cardinals broadcaster Mike Shannon has said the longest home run he has witnessed was hit by McCovey on Sept. 4, 1966, at St. Louis.

Cardinals broadcaster Mike Shannon has said the longest home run he has witnessed was hit by McCovey on Sept. 4, 1966, at St. Louis. “Money was the deciding factor, plain and simple,” McCarver said in his book “Oh, Baby, I Love It.”

“Money was the deciding factor, plain and simple,” McCarver said in his book “Oh, Baby, I Love It.” Caray was entering his 10th season as play-by-play voice of the Cardinals when Buck was chosen to join him after calling minor-league games for Rochester in 1953. Buck replaced former catcher Gus Mancuso as Caray’s broadcast partner.

Caray was entering his 10th season as play-by-play voice of the Cardinals when Buck was chosen to join him after calling minor-league games for Rochester in 1953. Buck replaced former catcher Gus Mancuso as Caray’s broadcast partner.

In 15 years with the Cardinals, 1974-88, Forsch pitched two no-hitters and helped St. Louis win the 1982 World Series title.

In 15 years with the Cardinals, 1974-88, Forsch pitched two no-hitters and helped St. Louis win the 1982 World Series title. At one point, a guy says to Bob, “We always wondered if your son played baseball.” And Bob said, “I have two daughters. I don’t have a son.” And the guy pointed at me and said, “Isn’t he your son?”

At one point, a guy says to Bob, “We always wondered if your son played baseball.” And Bob said, “I have two daughters. I don’t have a son.” And the guy pointed at me and said, “Isn’t he your son?”