Coveted by the NFL St. Louis Cardinals for his uncanny ability to return kickoffs and punts for good gains, as well as for his skills as a cornerback covering the game’s top receivers, Abe Woodson provided a bonus.

At a time when cornerbacks gave receivers lots of room at the line of scrimmage in the hope of not getting outmaneuvered, Woodson used a different technique _ the bump-and-run.

At a time when cornerbacks gave receivers lots of room at the line of scrimmage in the hope of not getting outmaneuvered, Woodson used a different technique _ the bump-and-run.

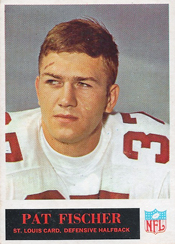

Sixty years ago, in 1965, when he was acquired from the San Francisco 49ers for running back John David Crow, Woodson taught his teammates in the Cardinals’ secondary, most notably Pat Fischer, how to line up closer to a receiver and, after the ball was snapped, bump him, throwing off the timing of the pass route.

Before long, Woodson’s effective bump-and-run technique was utilized throughout pro football until the NFL passed a rule in 1978, restricting its use.

Streaking to success

One of the best high school athletes in Chicago, Woodson went on to the University of Illinois and excelled in track (matching a world record in the 50-yard indoor high hurdles) and football (running back, defensive back, punter).

In a game against No. 1-ranked Michigan State in 1956, Woodson gave a performance reminiscent of The Galloping Ghost, Illinois legend Red Grange. Michigan State led, 13-0, at halftime, but Woodson scored three touchdowns in the second half, lifting Illinois to a 20-13 victory.

Helped by the blocking of fullback Ray Nitschke (the future Green Bays Packers linebacker), Woodson scored on a two-yard plunge, a 70-yard run (in which he took a pitchout, reversed his field and outran the secondary) and a screen pass that went for 82 yards. On that winning score, Woodson took the screen pass near the sideline, angled across the field and hurdled over a defender at the 30 before sprinting to the end zone.

Chicago Cardinals head coach Ray Richards said to the San Francisco Examiner, Woodson “rates as one of the five best backs in the country.”

The 49ers took him in the second round of the 1957 NFL draft but Uncle Sam’s draft took priority. Drafted into the Army, Woodson was inducted in January 1957 and had to skip the football season. He was 24 when he was discharged and joined the 49ers during the season in October 1958.

Though Woodson made his mark in college as a running back, 49ers head coach Frankie Albert needed help in the secondary and put Woodson there. The rookie made a good early impression when he tackled Chicago Bears halfback Willie Galimore, nicknamed the Wisp for how he slipped through defenses like a puff of smoke, and caused him to fumble.

As Woodson put it to the San Rafael Daily Independent, “I was switched to defense accidently. I accidently looked good in my first game.”

Los Angeles Times columnist Jim Murray suggested that using Woodson on defense instead of offense “was like asking Caruso if he could also tap dance,” but when Red Hickey replaced Albert as head coach in 1959, Woodson was given a starting cornerback spot. “Woodson has whistling speed and such remarkable reactions that Hickey can give him assignments which would trouble veteran defenders,” Sports Illustrated observed.

On the run

Stellar on defense, Woodson was in a special class on kickoff returns. In 1959, he stunned the crowd at the Coliseum in Los Angeles with a 105-yard kickoff return for a touchdown against the Rams. As the San Rafael Daily Independent described it: “Woodson sidestepped a couple of Rams with a perfect change of pace and then poured it on. He cut from one sideline to the other, shaking off pursuers, before drawing a direct bead on the goal line.” Video

On most kickoff returns, Woodson “starts out like a fat man dragging a sled” until he gets to the 20 and then turns on the sprinter’s speed, Jim Murray noted.

In games against the Detroit Lions in 1961, Woodson scored touchdowns on a kickoff return and a punt return. Asked to describe how it felt to return punts, Woodson told the San Rafael newspaper, “Like looking a tiger in the face.”

(In 1961, Red Hickey decided to experiment with Woodson at running back. In his first start, against the Minnesota Vikings, Woodson lost three fumbles and bobbled the ball five times. The experiment ended soon after.)

Woodson led the NFL in kickoff return average in 1962 (31.1 yards) and 1963 (32.2 yards). He averaged more than 21 yards per kickoff return each year from 1958-65. In 1963, Woodson had kickoff returns for touchdowns of 103 yards (Vikings), 99 yards (New York Giants) and 95 yards (Vikings again).

For the sheer excitement he created on the gridiron, the Modesto Bee called Woodson “the Willie Mays of football.”

During his first few years with the 49ers, Woodson worked in the off-seasons as a bank teller and then in the installment loan and credit analysis departments of Golden Gate National Bank.

In 1963, he joined the sales staff of Lucky Lager Brewing Company, California’s largest beer producer. The year before, “Lucky Lager was boycotted by Negro consumers in the southern California area because it did not have a Negro salesman,” the San Francisco Examiner reported.

Tricks of the trade

As a cornerback, Woodson “was quick and tricky,” Bears safety Roosevelt Taylor said to the San Francisco Examiner.

Woodson began using his signature trick, the bump-and-run, in 1963 against the Baltimore Colts. “We wanted to stop that Johnny Unitas to Raymond Berry surefire short pass to the sideline,” Woodson told Art Rosenbaum of the Examiner.

As Woodson explained to the San Rafael Daily Independent, “I know (Berry) can’t outrun me. So I decided to move up to him at the line of scrimmage. By staying right with him, it eliminates the double fake he uses so well. It makes him play my game. When you take away Berry’s moves, he’s just another end.”

(The receiver who gave Woodson the most problems was Max McGee of the Packers. “He has speed and he’s big,” Woodson told the Peninsula Times Tribune of Palo Alto. “He has some of the best moves in the league, and Bart Starr, the quarterback, hits him just at the right time.”)

Woodson credited 49ers defensive backs coach Jack Christiansen with giving him the idea for the bump-and-run. Christiansen, a former Lions defensive back, told the Examiner, “I borrowed it from Dick “Night Train” Lane when he played for the Chicago Cardinals in the 1950s … He used it if there was blitz coverage up front and man-to-man in the outer secondary. Then he’d line up four to five yards instead of the usual six to eight behind the line of scrimmage, pick up his man immediately, give him one shocker of a bump, and take it from there.”

American Football League defensive backs Willie Brown and Kent McCloughan of the 1960s Oakland Raiders also were considered pioneers of the bump-and-run.

“I think if you researched it deeply enough you’d find Amos Alonzo Stagg (who began coaching in the 1800s) probably picked it up from one of the math students at the University of Chicago,” Christiansen quipped to the Examiner. “There isn’t a whole lot that’s truly new in football.”

Change of scenery

Traded to the Cardinals in February 1965, Woodson, 31, was “regarded as the premier kickoff return specialist,” the St. Louis Post-Dispatch suggested. Columnist Bob Broeg noted, “Woodson still has speed and, above all, the ability to elude a tackler … He’s got better moves than a guy with itchy underwear.”

In a 1965 exhibition game versus the Colts, Woodson intercepted a Gary Cuozzo pass, scoring the Cardinals’ lone touchdown, and totaled 77 yards on three kickoff returns. However, in the exhibition finale against the Packers, he dislocated a shoulder. After sitting out the opener, Woodson returned kickoffs (averaging 24.6 yards on 27 returns) and punts, and provided backup at cornerback.

Woodson’s most significant contribution may have come on Dec. 5, 1965, when he showed Pat Fischer the bump-and-run technique against Rams receivers Jack Snow and Tommy McDonald.

“Abe came up and hit them, or held them up, as they came at him,” Fischer said to William Barry Furlong of the Washington Post. “All of a sudden, the precision that they were trained to run patterns at was lost. The receiver wasn’t concerned about getting off on the count, or where he was going to go. Now he was concerned about one thing: How am I going to get around that guy?”

Snow was limited to four catches for 38 yards; McDonald totaled two receptions for 27 yards. Game stats

Moving on

Under Charley Winner, who replaced Wally Lemm as Cardinals head coach in 1966, Woodson’s days as a kickoff and punt returner were finished. He was used exclusively at cornerback and started in 11 of the club’s 14 games.

Woodson used the bump-and-run to hold down fleet receivers such as the Dallas Cowboys’ Bob Hayes. “I don’t blame Abe Woodson for trying to stop me from going downfield,” Hayes told the Post-Dispatch. “I don’t think the Cardinals play dirty. They just play hard.”

Of Woodson’s four interceptions for the 1966 Cardinals, the most prominent secured a 6-3 victory against the Pittsburgh Steelers. With 1:20 left in the game, the Steelers drove into Cardinals territory but Woodson picked off a Ron Smith pass intended for Gary Ballman at the St. Louis 22. Game stats

Given a chance to go into executive training for a position with S&H Green Stamps, Woodson retired from football in February 1967. “He did a tremendous job for us (in 1966) and showed no sign of slowing down, either in coming up to stop runs or in covering pass receivers,” Charley Winner told the Post-Dispatch.

Woodson eventually settled into sales and management positions with an insurance company.

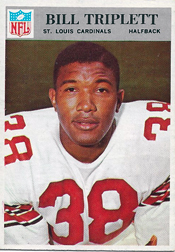

When the chest pain returned at dinner the next night, Triplett and his wife grew more concerned. At a visit to a doctor the following day, X-rays showed a dark spot on his right lung, Newspaper Enterprise Association reported.

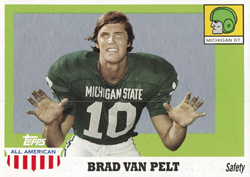

When the chest pain returned at dinner the next night, Triplett and his wife grew more concerned. At a visit to a doctor the following day, X-rays showed a dark spot on his right lung, Newspaper Enterprise Association reported. Michigan State’s Brad Van Pelt, a right-hander with a 100 mph fastball, was the prospect who prompted the Cardinals to consider coughing up the cash. He also was a football talent, a recipient of the Maxwell Award presented to the most outstanding college player in the sport.

Michigan State’s Brad Van Pelt, a right-hander with a 100 mph fastball, was the prospect who prompted the Cardinals to consider coughing up the cash. He also was a football talent, a recipient of the Maxwell Award presented to the most outstanding college player in the sport. Listed at 5 feet 9 and 170 pounds _ “Anyone who ever saw him in person knew even those measurements were somewhat exaggerated,” the Washington Post noted _ Fischer shed the blocks of Goliath-like guards and tackles, took down steamrolling fullbacks, and stymied rangy receivers during a 17-year NFL career with the Cardinals (1961-67) and Washington Redskins (1968-77).

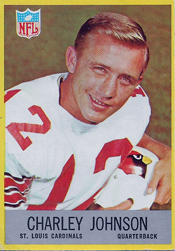

Listed at 5 feet 9 and 170 pounds _ “Anyone who ever saw him in person knew even those measurements were somewhat exaggerated,” the Washington Post noted _ Fischer shed the blocks of Goliath-like guards and tackles, took down steamrolling fullbacks, and stymied rangy receivers during a 17-year NFL career with the Cardinals (1961-67) and Washington Redskins (1968-77).  Charley Johnson was a good quarterback for 15 years in the NFL, including from 1961-69 with the St. Louis Cardinals. He led the NFL in completions (223) and passing yards (3,045) in 1964. His 170 career touchdown passes are more than the likes of Troy Aikman (165), Roger Staubach (153) and Bart Starr (152).

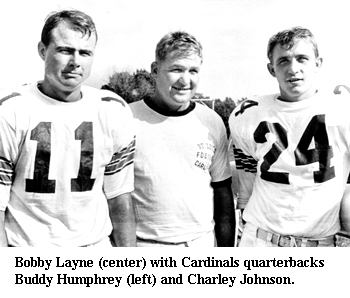

Charley Johnson was a good quarterback for 15 years in the NFL, including from 1961-69 with the St. Louis Cardinals. He led the NFL in completions (223) and passing yards (3,045) in 1964. His 170 career touchdown passes are more than the likes of Troy Aikman (165), Roger Staubach (153) and Bart Starr (152). In 1965, Layne joined the St. Louis Cardinals as quarterback coach, helping to refine Charley Johnson.

In 1965, Layne joined the St. Louis Cardinals as quarterback coach, helping to refine Charley Johnson.