Johnny Stuart was a rattled rookie when he made his first start in the majors for the Cardinals and failed to get an out. A year later, on the day he made his second start in the big leagues, he also made his third, and the results were much better.

On July 10, 1923, Stuart started both games of a doubleheader for the Cardinals against the Braves and earned complete-game wins in both.

On July 10, 1923, Stuart started both games of a doubleheader for the Cardinals against the Braves and earned complete-game wins in both.

The iron man feat was a highlight of his four seasons in the majors with the Cardinals, but it wasn’t his only impressive sports accomplishment.

Razzle dazzle

Stuart played baseball and football at Ohio State University. He was a halfback, punt returner and punter for the football team.

In those days, players were taught to just fall on a punted ball that hit the ground rather than risk a fumble. Fleet and sure-handed, Stuart had other ideas. According to a syndicated column in The Cincinnati Post, “He handles a football that is rolling along the ground just as if it was a grounder in baseball. Stuart has thrown tradition to the wind in handling such punts. He races in on them on the bound and is on the way toward the opposition goal at full speed.”

His daring approach sparked Ohio State to victory against Michigan in 1921.

Scoreless in the second quarter, Michigan punted from deep in its territory. It was a lousy kick and the ball wobbled to the Michigan 34-yard line.

“With the agility of a cat, Stuart pounced on the pigskin,” the Detroit Free Press reported. “With the narrow margin of three yards, Stuart managed to twist through many aspiring Michigan tacklers.”

According to the Cleveland Plain Dealer, Stuart “swept past the entire astonished and dumbfounded Michigan team” and crossed the goal line for a touchdown.

Stuart’s punting was as important as his touchdown because he kept Michigan’s offense from getting good field position. “Time and again Stuart kicked the ball 50 and 60 yards,” the Free Press reported. “His punts were all well-placed and Michigan men found them difficult to gather in.”

Ohio State won, 14-0, putting “Johnny Stuart’s name on the lips of every Ohio State rooter,” the Plain Dealer noted.

The big show

Football was fun but baseball offered Stuart his best chance at a professional career. A right-hander, he excelled as a college pitcher and the Cardinals were impressed. They signed him in July 1922 and brought him directly to the majors.

When he left his home in Huntington, W. Va., and joined the Cardinals in New York, Stuart “was not even city broke,” let alone ready to face batters in the big leagues, the Springfield (Ohio) News-Sun reported.

On July 27, 1922, one day after Stuart joined the team, manager Branch Rickey gave him the start against the reigning World Series champion Giants at the Polo Grounds. The Cardinals (57-38), who trailed the first-place Giants (56-34) by 1.5 games, were in the middle of a stretch of eight games in seven days and Rickey hoped Stuart could give the rotation a lift.

The task, though, was daunting. The Giants, managed by the irascible John McGraw, had a lineup that featured three future Hall of Famers (Dave Bancroft, Frankie Frisch and High Pockets Kelly) and an outfielder, Casey Stengel, who was batting .387 for the season.

Cardinals batters did their best to help the rookie, scoring four in the top of the first against two-time 20-game winner Jesse Barnes, but when it came Stuart’s turn to take the mound the 4-0 lead was no comfort to him.

“Stuart became all fussed before he got started,” the New York Daily News noted.

According to the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, Stuart, 21, was “unnerved by the taunts hurled at him from the Giants’ bench and from the spectators.”

He walked the first batter (Bancroft), then committed a balk, hit the second batter (Johnny Rawlings) with a pitch, and threw a couple of balls out of the strike zone to the third batter (Frisch) before being removed by Rickey.

Two of the runners Stuart put on eventually scored. The Giants won, 12-7. Boxscore

“Several baseball critics over the country are poking fun at manager Branch Rickey in starting Johnny Stuart against the Giants when first place was at stake,” the Springfield (Ohio) News-Sun reported.

The day after his inauspicious big-league debut, Stuart pitched two innings of relief against the Giants and allowed a two-run single to Frisch. Boxscore

Mercifully, the Cardinals shipped him to a farm club, the Syracuse Stars, managed by Shag Shaughnessy, a former baseball and football standout at Notre Dame.

Start me up

Eager to see how Stuart developed after his stint at Syracuse, Rickey included him on a team of prospects he took on a barnstorming tour after the 1922 season. Stuart impressed, pitching a no-hitter against a team of locals in De Soto, Mo., the St. Louis Star-Times reported.

After a good spring training, Stuart earned a spot on the Cardinals’ 1923 Opening Day roster as a reliever. Throughout the season, he “carried with him a tennis ball, which he gripped and squeezed continually to improve the strength of his pitching hand,” the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported.

Stuart also became a protege of Fred Toney, 34, a two-time 20-game winner who was with the 1923 Cardinals for his 12th and final season in the majors. Toney taught Stuart to throw a fadeaway ball and how to pitch to a batter’s weakness. “He and Toney were constantly talking baseball,” the Post-Dispatch noted.

Stuart made 17 appearances, all in relief, for the 1923 Cardinals before Rickey chose him to start the opener of a July 10 doubleheader against the Braves at Boston. It was Stuart’s first start for the Cardinals since his rough debut versus the Giants a year earlier.

The result this time was much different. Stuart pitched a three-hitter and the Cardinals cruised to an 11-1 victory. Stuart finished strong, getting 12 consecutive outs after Stuffy McInnis led off the sixth with a single. Boxscore

Stuart then asked Rickey to start him in the second game. “There is a dearth of pitchers on the Cardinals club right now,” the Globe-Democrat reported, so Rickey accepted Stuart’s offer.

Stuart retired the first four batters of Game 2 before Tony Boeckel bunted for a single. He held the Braves to a run through seven innings, then gave up two in the eighth, but completed the game, a 6-3 Cardinals triumph.

“It was not until the very end of his second game that he showed the least signs of wear and tear,” the Boston Globe reported.

One of the keys for Stuart was that he induced the Braves to hit into outs. He didn’t strike out a batter in his 18 innings. Boxscore

On Sept. 3, 1923, Stuart pitched a five-hit shutout in the Cardinals’ 1-0 triumph against the Cubs at Chicago. In the fourth inning, two outs came on his pickoffs of runners at first base. Boxscore

Stuart, 22, finished the 1923 season with a 9-5 record. He was 7-2 as a starter.

“His fastball is sweet and he has developed a slow fadeaway which bothers the best hitters in the league,” the Star-Times reported.

Fade away

Stuart was the Cardinals’ 1924 Opening Day starter against the Cubs, but got the flu in late May and didn’t make a start in June. He recovered, pitched a four-hitter against the Pirates on July 1 but finished the season 9-11 with a 4.75 ERA.

Returned to the bullpen in 1925, Stuart struggled. On May 21, he gave up 10 runs against the Braves. A month later, he was shelled for 16 runs versus the Pirates.

Rogers Hornsby replaced Branch Rickey as manager and when the Cardinals, assured of a fourth-place finish, went to Chicago for the final series of the season, he gave Stuart a start against the Cubs. Matched against Grover Cleveland Alexander, Stuart responded with a four-hitter in a 4-3 Cardinals triumph. Boxscore

It turned out to be Stuart’s final big-league game. He was 24 years old. His overall Cardinals record: 20-18, including 5-0 against the Cubs.

In 1927, Stuart was hired to be a college head coach of the baseball and basketball teams at Marshall in the town he resided, Huntington, W. Va. He later became manager of a minor-league team in Huntington and operated a baseball school there.

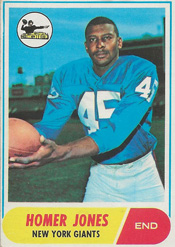

A receiver with the 1960s New York Giants, Jones was a master at producing long gains. He did it either one of two ways _ hauling in deep passes, or using his deft footwork to add yardage after a grab. His career average of 22.3 yards per catch is a NFL record.

A receiver with the 1960s New York Giants, Jones was a master at producing long gains. He did it either one of two ways _ hauling in deep passes, or using his deft footwork to add yardage after a grab. His career average of 22.3 yards per catch is a NFL record. On Nov. 20, 1983, Coryell brought the San Diego Chargers to Busch Stadium to play the Cardinals.

On Nov. 20, 1983, Coryell brought the San Diego Chargers to Busch Stadium to play the Cardinals. When he was elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame on Feb. 9, 2023, Coryell correctly was hailed as an innovator whose offenses with the Cardinals, and later the San Diego Chargers, were thrilling to watch and nerve-wracking to defend.

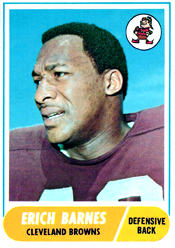

When he was elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame on Feb. 9, 2023, Coryell correctly was hailed as an innovator whose offenses with the Cardinals, and later the San Diego Chargers, were thrilling to watch and nerve-wracking to defend. Two of Barnes’ most significant clashes with the Cardinals occurred in consecutive seasons (1966 and 1967) at St. Louis. The first illustrated his fiery intensity. The second showed his smarts.

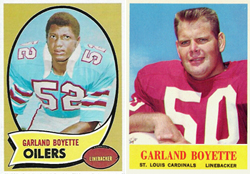

Two of Barnes’ most significant clashes with the Cardinals occurred in consecutive seasons (1966 and 1967) at St. Louis. The first illustrated his fiery intensity. The second showed his smarts. Two years later, the Cardinals cut him, but that wasn’t the only insult he endured. Philadelphia Chewing Gum Corporation produced a football card of Boyette that year, but fumbled the assignment. The name on the card was Garland Boyette, but the photo was of Don Gillis, a former Cardinals center who no longer was in the league. Boyette was black and Gillis was white.

Two years later, the Cardinals cut him, but that wasn’t the only insult he endured. Philadelphia Chewing Gum Corporation produced a football card of Boyette that year, but fumbled the assignment. The name on the card was Garland Boyette, but the photo was of Don Gillis, a former Cardinals center who no longer was in the league. Boyette was black and Gillis was white.