St. Louis tried to attract the nation’s best athlete at a time when its teams, Browns and Cardinals, were the worst in major-league baseball. Jim Thorpe, however, chose to enter the majors at the top, with the 1913 New York Giants.

A two-time Olympic gold medalist in track and field as well as a football standout, Thorpe wasn’t as prominent in baseball. For six seasons in the National League with the Giants, Reds and Braves, he mostly was a spare outfielder.

A two-time Olympic gold medalist in track and field as well as a football standout, Thorpe wasn’t as prominent in baseball. For six seasons in the National League with the Giants, Reds and Braves, he mostly was a spare outfielder.

The team Thorpe did best against was St. Louis. A career .252 hitter, Thorpe batted .314 overall versus the Cardinals and .339 in games played at St. Louis.

Bright Path

A citizen of the Sac and Fox Nation, James Francis Thorpe and a twin brother, Charles, were born in what is now Oklahoma. (Charles died of pneumonia as a youth.) Jim Thorpe also was known as Wa-Tho-Huck, which in the Sac and Fox language means “Bright Path,” according to the Oklahoma Historical Society.

After attending schools in Oklahoma and Kansas, Thorpe enrolled at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania when he was 16 in 1903 and excelled in athletics, especially football and track, for coach Pop Warner.

Thorpe also was proficient at archery, baseball, basketball, canoeing, handball, hockey, horsemanship, lacrosse, rifle shooting, skating, squash and swimming, according to The Sporting News.

Carolina in my mind

Taking a break from Carlisle in 1909, Thorpe, 22, signed to play minor-league baseball for the Rocky Mount (N.C.) Railroaders, a Class D club in the Eastern Carolina League. He was paid $12.50 to $15 per week, plus room and board, team secretary E.G. Johnston told the Rocky Mount Telegram.

A right-hander, Thorpe pitched and played right field. Speed was his main attribute. Eyewitness accounts told of him scoring from first on a single to right and racing to the plate from second on an infield out. His statistics that season were nothing special (9-10 record, .254 batting mark), but he was the talk of the town. A local sports reporter, Sam Mallison, noted, “Few Rocky Mount citizens had ever seen one of these original Americans.”

Rocky Mount was a segregated town of about 8,000 in 1909. It had a prominent railroad yard, cotton mills and tobacco farms. At that time, “The horse and buggy still provided the principal method of transportation between points not connected by the railroad,” Sam Mallison recalled in the Rocky Mount Telegram. “There were no hard-surfaced highways and few paved streets.”

As for baseball, Thomas McMillan Sr. wrote in the Telegram, “In those days, the players dressed for the game in their rooms (and) walked to the ballpark. Many stayed at the new Cambridge Hotel, a short block north of the passenger train station. The players would be met by a crowd of little boys as they came out of the hotel. Each boy sought the privilege of carrying the shoes or glove or bat for one of the ballplayers. Carrying a glove or a pair of shoes meant free admission to the game. I was one of those little boys and big Jim Thorpe seemed to favor me as his shoes and glove caddy. I remember Jim perfectly. Black hair, black eyes, high cheekbones in a mahogany face, and a physique that gave an impression of strength rather than mere size. His movements were quick and lithe.”

Thorpe returned to Rocky Mount in 1910, but the luster was lost. According to Sam Mallison, “(Thorpe’s) custom, in the early evening, was to take a snoot full … As time went on, (drinking) took hold of Jim earlier in the day, occasionally before the noon hour, and this, plus the fact that opposing pitchers had learned he was a sucker for a curveball on the outside (corner), diminished his speed and caused his batting average to plummet … (Thorpe) had ceased to be such an enormous gate attraction, and his antics were the despair of both the field manager and the front office. He ignored the rules and was wholly unresponsive to managerial direction. In short, he became a problem child.”

That summer, Thorpe was traded to the Fayetteville (N.C.) Highlanders and finished the 1910 season with them.

Glory and scandal

Thorpe re-enrolled at Carlisle and rocketed toward his athletic peak. He gained national fame as a consensus first-team football all-America in 1911 and 1912. He rose to worldwide prominence at the 1912 Summer Olympics in Stockholm, winning gold medals in the decathlon and pentathlon. Thorpe was the first Native American to win an Olympic gold medal for the United States.

“To a whole generation of American sports lovers, Jim Thorpe was the greatest athlete of them all,” the New York Times declared. “No one has equaled the hold that he had on the imagination of all who saw him in action … He was a magnificent performer.”

In January 1913, after the International Olympic Committee learned of Thorpe’s minor-league ballplaying, it was determined he had competed in the 1912 Games as a professional, violating the rules of amateurism. He was stripped of his medals and his achievements were erased from the Olympic records. “The committee’s insistence that the Olympics are amateur is as fatuous as its insistence that sports should never be soiled by politics,” the New York Times opined.

(In July 2022, 69 years after Thorpe’s death, the International Olympic Committee declared him sole winner of the 1912 Olympic decathlon and pentathlon.)

Looking to extend his athletic career, Thorpe saw big-league baseball as offering the best path. (The American Professional Football Association, which became the NFL, wasn’t established until 1920).

On the money

Thorpe got offers from five big-league clubs _ Browns, Giants, Pirates, Reds and White Sox, the New York Times reported.

The Browns had more than 100 losses in three consecutive seasons (1910-12) and would finish in last place in the American League at 57-96 in 1913, but club owner Robert Hedges was serious about a pursuit of Thorpe. Hedges had scout Pop Kelchner try to woo Thorpe to St. Louis. On Kelchner’s recommendation, the Browns acquired a minor-league shortstop, Mike Balenti. He and Thorpe played together in the Carlisle football team backfield. The Browns hoped having Balenti would help them land Thorpe.

On Jan. 24, 1913, the St. Louis Globe-Democrat reported, “It was learned yesterday that Jim Thorpe … had promised Hedges that if he played ball in professional circles he would join the Browns.”

A week later, though, Thorpe signed with the Giants. Led by manager John McGraw, the Giants won National League pennants in 1911 and 1912. They’d go to the World Series again in 1913. Perhaps most important of all to Thorpe was the money. The Giants offered a salary of more than $5,000, the New York Times reported. According to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Thorpe got a $6,000 salary and a $500 signing bonus, and Carlisle coach Pop Warner got $2,500 from the Giants for steering Thorpe to them.

“There are very few $6,000 ballplayers in the game today,” St. Louis columnist Sid Keener noted. According to Keener, that select group included Ty Cobb, Ed Konetchy, Nap Lajoie, Christy Mathewson and Tris Speaker.

Though McGraw never had seen Thorpe play, he told the New York World, “A wonderful athlete like Thorpe ought to have in him the makings of a great ballplayer. He has the muscle and the brain, and it is up to me to locate the spot where he will be of most value to the team.”

Cardinals calling

After seeing Thorpe in spring training, McGraw determined the best spot for him was on the bench, or maybe the minors. Thorpe, who turned 26 that year, was plenty fast and strong, but he misjudged fly balls, didn’t slide properly and couldn’t hit the curve consistently.

In April 1913, before the regular season got under way, McGraw apparently considered placing Thorpe on waivers. If Thorpe was available, Cardinals manager Miller Huggins was determined to get him.

“Jim Thorpe … may become a Cardinal,” the Bridgeport Times of Connecticut reported. “All that is needed for (Thorpe) to join the (Cardinals) is for John McGraw to accept an offer made by Miller Huggins. It is believed that waivers have been asked on Thorpe because Huggins sent the following telegram to McGraw: Will take Thorpe off your hands. What is his salary?”

According to the New York Herald, Huggins said the Cardinals, destined to finish with the worst record in the majors (51-99) that year, would spend “the extreme limit” for Thorpe.

Huggins told Sid Keener, “I believe Thorpe can be developed into a ballplayer. He has what I want _ speed. It may be that he will need plenty of seasoning, but I would be willing to carry him a year or so as a utility player.”

The Cardinals’ eagerness to take Thorpe apparently gave McGraw pause. He decided Thorpe would remain with the Giants. “I can make a first-class player of him,” McGraw said, according to the Montpelier (Vermont) Morning Journal.

Playing on

Thorpe stuck with the Giants in 1913 and 1914, but rarely played. He spent most of 1915 in the minors. Sent to minor-league Milwaukee in 1916, Thorpe made significant progress. He led Milwaukee in total bases (240) and hits (157).

In 1917, the Giants loaned Thorpe to the Reds. McGraw’s friend and former ace, Christy Mathewson, was the Reds’ manager. In a game against the Cardinals, Thorpe had two hits and two RBI. In another, at St. Louis, he totaled four hits, three RBI and scored twice. Boxscore and Boxscore

Thorpe’s highlight with the Reds, though, came in a game at Chicago. Fred Toney of the Reds and Hippo Vaughn of the Cubs each pitched nine hitless innings. In the 10th, Thorpe’s single versus Vaughn drove in a run and the Reds won, 1-0. Boxscore

After four months with the Reds, Thorpe was returned to the Giants. He played for them in 1918, then was traded to the Braves. Thorpe hit .327 for Boston in 1919 and .354 versus the Cardinals. It wasn’t enough to keep him in the majors, but he wasn’t through with baseball. Thorpe played three more seasons in the minors and thrived, batting .360 for Akron in 1920 and .358 for Toledo in 1921.

Meanwhile, when the American Professional Football Association began in 1920, Thorpe was welcomed in as player-coach of the Canton Bulldogs.

In 1925, Thorpe, 38, was a running back with the NFL New York Giants. He is one of two men who played for both the NFL and baseball New York Giants. The other, Steve Filipowicz, was an outfielder with the baseball Giants (1944-45) and a running back with the football Giants (1945-46).

Thorpe finally got to play for the Cardinals, too. His last NFL game was with the Chicago Cardinals in 1929.

Read Full Post »

Seven years after hitting a walkoff home run for the Pirates in the ninth inning of Game 7 in the 1960 World Series against the Yankees’ Ralph Terry, Mazeroski was hired to make an out in the film “The Odd Couple.” Actually, the role required he make three outs _ with one swing.

Seven years after hitting a walkoff home run for the Pirates in the ninth inning of Game 7 in the 1960 World Series against the Yankees’ Ralph Terry, Mazeroski was hired to make an out in the film “The Odd Couple.” Actually, the role required he make three outs _ with one swing. He played in a World Series with the Cincinnati Reds. He was a head coach in college and pro football. He took a team to the Rose Bowl. He led the Philadelphia Eagles to two NFL championships.

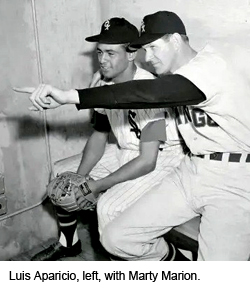

He played in a World Series with the Cincinnati Reds. He was a head coach in college and pro football. He took a team to the Rose Bowl. He led the Philadelphia Eagles to two NFL championships. Marty Marion was the White Sox manager who brought Aparicio to the major leagues and made him the starting shortstop as a rookie in 1956.

Marty Marion was the White Sox manager who brought Aparicio to the major leagues and made him the starting shortstop as a rookie in 1956. A two-time Olympic gold medalist in track and field as well as a football standout, Thorpe wasn’t as prominent in baseball. For six seasons in the National League with the Giants, Reds and Braves, he mostly was a spare outfielder.

A two-time Olympic gold medalist in track and field as well as a football standout, Thorpe wasn’t as prominent in baseball. For six seasons in the National League with the Giants, Reds and Braves, he mostly was a spare outfielder. Cabrera is the only person born in the Canary Islands to play baseball in the big leagues. The shortstop was 32 when he debuted with the Cardinals in 1913.

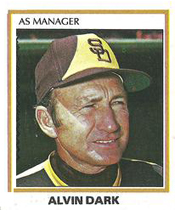

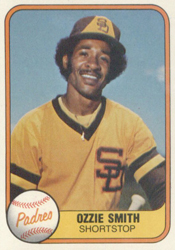

Cabrera is the only person born in the Canary Islands to play baseball in the big leagues. The shortstop was 32 when he debuted with the Cardinals in 1913. When the Padres opened spring training camp in 1978, Dark made a daring decision. The manager named Ozzie Smith the starting shortstop.

When the Padres opened spring training camp in 1978, Dark made a daring decision. The manager named Ozzie Smith the starting shortstop. In the fall, the Padres put Smith on their Arizona Instructional League team. Hall of Fame second baseman Billy Herman, a Padres minor-league hitting instructor, saw him and was impressed. Then Alvin Dark arrived.

In the fall, the Padres put Smith on their Arizona Instructional League team. Hall of Fame second baseman Billy Herman, a Padres minor-league hitting instructor, saw him and was impressed. Then Alvin Dark arrived.