Willie Mays was the first right-handed batter to hit 400 home runs in the National League. The milestone homer came against a familiar foe, Curt Simmons of the Cardinals, and was witnessed by another 400-homer hitter, Stan Musial.

On Aug. 27, 1963, at Candlestick Park in San Francisco, Mays capped a two-month hot streak with his 400th career home run for the Giants.

On Aug. 27, 1963, at Candlestick Park in San Francisco, Mays capped a two-month hot streak with his 400th career home run for the Giants.

At the time, nine others had achieved the feat: Babe Ruth (714), Jimmie Foxx (534), Ted Williams (521), Mel Ott (511), Lou Gehrig (493), Stan Musial (472), Eddie Mathews (419), Mickey Mantle (415) and Duke Snider (403).

(Musial, Mathews, Mantle and Snider still were active. Musial would finish with 475, Mathews 512, Mantle 536 and Snider 407.)

The only right-handed batter in the 400-homer group besides Mays was Foxx. (Of his 534 home runs, Foxx hit 524 as an American Leaguer and 10 as a National Leaguer.) All the others, except Mantle (a switch-hitter), batted from the left side.

Mays, 32, was considered the best bet to break the National League career home run mark of 511 held by Mel Ott.

On a roll

After leading the National League in home runs (49) and total bases (382) and powering the Giants to a pennant in 1962, Mays got baseball’s highest salary in 1963 _ $105,000.

He had a substandard start to the season, hitting .233 in April and .257 in May. At the urging of the Giants, Mays got his eyes examined “and was told they were fine,” according to his biographer James S. Hirsch.

He found a groove after the all-star break and nearly was unstoppable. Mays hit .322 in July, .387 in August and .378 in September.

From July 28 through Aug. 27, Mays hit safely in 27 of 28 games. In that stretch, he raised his 1963 season batting average from .274 to .308.

His only hitless game in that period came on Aug. 13 when Jim Maloney of the Reds shut out the Giants on a two-hitter.

(The game was noteworthy for another reason. It was the first time Mays played a position other than center field in the majors. In the eighth inning, after Norm Larker batted for shortstop Ernie Bowman, manager Al Dark put Larker at first base, moved Orlando Cepeda from first to left, Harvey Kuenn from left to right, Felipe Alou from right to center and Mays from center to shortstop. Mays had no fielding chances in his one inning at short, but he told the Associated Press, “Man, that’s too close to the plate.” Boxscore)

Numbers game

On Aug. 25, 1963, facing the Reds’ Joe Nuxhall at Candlestick Park, Mays hit his 399th home run. Later , with Joey Jay pitching, Mays drove a pitch to deep left. “If Frank Robinson hadn’t caught the ball a scant foot from the top railing, Willie would have had his 400th major-league homer,” The Sporting News reported.

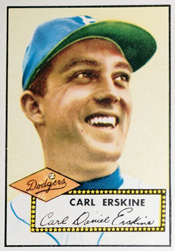

The next day, Aug. 26, the Cardinals opened a series at San Francisco. Mays got two singles, but no home run, against Ernie Broglio. Curt Simmons provided another opportunity on Aug. 27.

Mays had a history of success against Simmons. In 1961, for instance, Mays had a .692 on-base percentage versus the Cardinals left-hander, reaching base nine times (six hits, two walks, one hit by pitch) in 13 plate appearances. For his career, Mays finished with a .423 on-base percentage (39 hits, 22 walks, two hit by pitches) versus Simmons.

In the Aug. 27 game, with the Giants ahead, 3-0, Mays led off the third inning and lined a 2-and-1 pitch from Simmons the opposite way to right. The ball carried over the outstretched glove of George Altman, struck a railing and went over the fence for home run No. 400.

Orlando Cepeda followed with another homer against Simmons, who then was lifted for Barney Schultz. The first batter he faced, Felipe Alou, hit the Giants’ third consecutive home run of the inning. Boxscore

“I stay in good shape and I think I can hit a lot more,” Mays said to United Press International. “I may be able to reach the 500 mark.”

Stan Musial, stationed in left field when Mays hit his 400th homer, told The Sporting News, “He has an excellent chance to beat Mel Ott’s National League mark of 511 before he decides to call it quits.”

Asked about Musial, who had declared two weeks earlier that he would retire after the 1963 season, Mays said to Si Burick of the Dayton Daily News, “Nicest man I ever knew. When I was a kid coming up, I never thought a star on another team would help you, but he talked to me a lot about hitting. He even let me use his lighter bat a couple times when I was in a slump.”

(The kindness shown by Musial was paid forward by Mays. A week after Mays’ 400th home run, Cardinals pitcher Bob Gibson hit a 400-foot homer against the Pirates’ Don Schwall with a bat Mays had given him, The Sporting News reported. At 34 ounces, it was two ounces heavier than Gibson’s bat. Boxscore)

Join the club

On the same day Mays hit his 400th home run, Hank Aaron of the Braves slugged his 333rd (against Don Nottebart of the Houston Colt .45s). Three years later, on April 20, 1966, Aaron achieved home run No. 400 versus the Phillies’ Bo Belinsky.

Aaron went on to hit 755 home runs and Mays finished with 660.

In his book, “I Had a Hammer,” Aaron said, “I considered Mays a rival, certainly, but a friendly rival. At the same time, I would never accept the position as second best (to him). I’ve never seen a better all-around ballplayer than Willie Mays, but I will say this: Willie was not as good a hitter as I was. No way.”

In August 2023, 60 years after Mays became the 10th player to reach 400 career home runs, the total number of players achieving the feat had risen to 58.

When he felt overwhelmed, he walked out on his team. He did that multiple times in stints with the Padres, Giants and Astros.

When he felt overwhelmed, he walked out on his team. He did that multiple times in stints with the Padres, Giants and Astros. In 1953, the Cardinals were 0-11 for the season against the Dodgers at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn’s Flatbush section.

In 1953, the Cardinals were 0-11 for the season against the Dodgers at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn’s Flatbush section. Duke Carmel certainly fit the part. He was named after Duke Snider, had the mannerisms of Ted Williams and could hit with the power of Mickey Mantle.

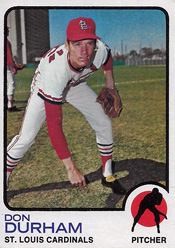

Duke Carmel certainly fit the part. He was named after Duke Snider, had the mannerisms of Ted Williams and could hit with the power of Mickey Mantle. A rookie right-hander with St. Louis in 1972, Durham had as many home runs (two) as wins (two). He batted .500 (seven hits in 14 at-bats) and had a slugging percentage of .929.

A rookie right-hander with St. Louis in 1972, Durham had as many home runs (two) as wins (two). He batted .500 (seven hits in 14 at-bats) and had a slugging percentage of .929. In the ninth inning, with the score tied at 5-5, reliever

In the ninth inning, with the score tied at 5-5, reliever