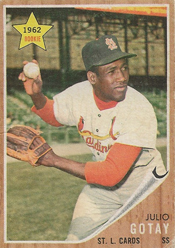

Red Schoendienst, who knew a thing or two about baseball skill, said Julio Gotay reminded him of Pepper Martin. Branch Rickey, another pretty good talent evaluator, insisted the Cardinals would be better with Gotay than with Dick Groat.

In 1962, Gotay was the Cardinals’ starting shortstop.

In 1962, Gotay was the Cardinals’ starting shortstop.

He turned out to be a can’t-miss prospect who did _ miss, that is.

Gotay had the athletic ability, but apparently lacked most of the rest of what it took to do the job for the Cardinals.

Fast rise

Born and raised in Puerto Rico, Gotay was a teenager playing amateur baseball there when he was spotted by former Cardinals catcher Mickey Owen, who was managing a winter league club. Owen told the Cardinals about Gotay and they signed him, sight unseen, on Owen’s recommendation, according to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

In 1957, the year he turned 18, Gotay began his professional career in the Cardinals’ system, playing for teams in Florida and Virginia. The following season, he was assigned to Winnipeg and got a chilly reception. The Canadian club’s first three games were called off because of “the heaviest snowfall of the year combined with record-low temperatures,” The Sporting News reported.

It was the first time Gotay saw snow.

Warming to the challenge, Gotay hit .323 with 24 home runs and 95 RBI as the Winnipeg third baseman.

Intrigued, the Cardinals invited Gotay, 19, to work with the big-league team at spring training in 1959. Marty Marion, the shortstop on the Cardinals’ four pennant-winning teams of the 1940s, was brought in to provide instruction to Gotay. Marion’s mission was to teach him to be a shortstop.

Alex Grammas had been projected to be the shortstop for the 1959 Cardinals until manager Solly Hemus became enamored of Gotay. “He’ll have to play himself off the ballclub,” Hemus, a former shortstop, told the Post-Dispatch.

In addition to swinging “a vicious bat,” Gotay displayed “a powerful throwing arm, good ranging ability and deft hands … He has handled several bad bounces by split-second shifting of his glove,” The Sporting News reported.

As the 1959 opener approached, the Cardinals decided to stick with Grammas because of his smooth fielding and big-league experience, and send Gotay to the minors to continue his development.

According to The Sporting News, Marion recommended the Cardinals put Gotay with a Class A team. Instead, he was assigned to Class AA Tulsa.

Jittery play

Gotay made 50 errors with Tulsa in 1959, but hit .284 with 17 home runs. Cardinals scout Fred Hawn told the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, “He’ll be one of the most exciting players in the majors in a couple of years.”

The Cardinals promoted Gotay to Class AAA Rochester in 1960, but he slumped and complained of a nervous stomach. Sent back to Tulsa, Gotay relaxed and played better.

In August 1960, when injuries left the Cardinals with a depleted bench, they called up Gotay. In his first at-bat in the majors, he singled against the Reds’ Joe Nuxhall. Boxscore

Gotay should have been a candidate for a spot on the 1961 Cardinals, but he developed an eye infection, missed most of spring training and was assigned to Class AAA.

Daryl Spencer began the season as the Cardinals’ shortstop but was traded to the Dodgers in May. The Cardinals tried Grammas and Bob Lillis but neither hit well enough. Next, they called up Gotay.

Experiencing what The Sporting News called “butterflies under major-league pressure,” Gotay made three errors at Pittsburgh in his first start. Boxscore

In a game at Cincinnati, two wild throws by Gotay landed in different dugouts on consecutive plays. In trying to complete a double play on a grounder by Vada Pinson, Gotay’s throw sailed into the first-base dugout and Pinson advanced to second. On the next play, Gotay fielded a grounder and tried to throw out Pinson at third, but the ball went into the third-base dugout and Pinson scored. Boxscore

In 10 June starts at shortstop for the 1961 Cardinals, Gotay made 10 errors. Returned to Class AAA, Gotay mostly played second base and hit .307.

High hopes

After the 1961 season, Cardinals general manager Bing Devine tried to acquire power-hitting shortstop Woodie Held from the Indians, “but I don’t see how we can give up what they want,” he told The Sporting News.

A factor in Devine’s decision to end his pursuit of Held was the play of Gotay in winter ball at Puerto Rico. Cardinals manager Johnny Keane went to Puerto Rico for a week, specifically to watch Gotay, and filed an encouraging report.

Devine said, “Gotay is having his best winter ever. He has become more confident, which may help overcome his tendency to be erratic. We know he has the ability.”

Competing against another prospect, Jerry Buchek, and Grammas at spring training, Gotay won the starting shortstop job with the 1962 Cardinals.

“Julio has a tremendous amount of raw ability,” Keane told The Sporting News. “I’m elated over what he has shown me.”

Red Schoendienst, a player-coach with the 1962 Cardinals said, “Gotay reminds me of (1930s Gashouse Gang player) Pepper Martin because he’s awkward but quick and effective. Strong, too. He’ll make it.”

Gotay, who joined an infield of Bill White, Julian Javier and Ken Boyer, performed well early in the season. He hit .302 in April and .313 in May. A 12-game hitting streak raised his batting mark to .333 on May 4. A week later, he went 4-for-4 and reached base six times in a game versus the Dodgers. Three of those hits came against Sandy Koufax. Boxscore

Gotay fielded well, too, He made three errors in 15 games in April and four errors in 30 games in May.

The Sporting News declared that Gotay “stands a good chance of having the longest reign as a Cardinals shortstop since Marty Marion’s day.”

Magic missing

After that, Gotay’s season began to unravel. He hit .214 in June and .205 in July. He made as many errors in June as he did in the first two months combined.

In his book “Stranger to the Game,” Cardinals pitcher Bob Gibson said Gotay “seemed to have all of the physical skills. We would learn the hard way, however, that the physical skills aren’t always enough.”

According to Gibson, Gotay “was interested in neither discipline nor fundamentals, which translated into an uncommon number of errors and foolish mistakes.”

In addition, Gibson said, Gotay “kept spooking us with voodoo. Most of us didn’t take the voodoo seriously, but now and then things would happen to make us a little uneasy.”

Gotay finished the 1962 season with a .255 batting average and 24 errors in 120 games. His main problem, The Sporting News suggested, “seems to be chiefly a matter of emotion and lack of maturity.”

Devine wanted to trade Gotay to the Pirates for shortstop Dick Groat, but Branch Rickey, who rejoined the Cardinals as a consultant and had the ear of club owner Gussie Busch, “still is high on Gotay,” The Sporting News reported.

In November 1962, Rickey reluctantly relented and Devine made the swap, but “Rickey hated the deal,” author David Halberstam wrote in “October 1964.”

Groat turned out to be the answer to the Cardinals’ shortstop need. He helped them contend in 1963 and become World Series champions in 1964.

Gotay was a bust with the Pirates. He went on to become a utility player with the Angels and Astros. He finished his playing career in 1971, hitting .302 for the Cardinals’ Tulsa farm team.

Though Gotay didn’t develop into an all-star, he had noteworthy achievements.

In a 1967 game versus the Cardinals, Gotay was 5-for-5. Four of the hits came against Bob Gibson. Boxscore

For his career, Gotay worked his voodoo versus Gibson, hitting .500 (8-for-16) against him. He also hit .438 (7-for-16) against Juan Marichal and .667 (4-for-6) versus Whitey Ford.

A nephew, Ruben Gotay, spent time in the Cardinals’ farm system and played in the majors with the Royals, Mets and Braves.

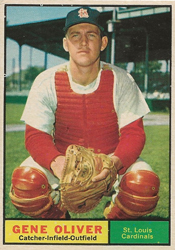

In 1962, Oliver was the Cardinals’ starting catcher. He got the job because the Cardinals thought he could hit with consistent power and drive in runs. Instead, he finished fourth on the club in home runs (14) and sixth in RBI (45).

In 1962, Oliver was the Cardinals’ starting catcher. He got the job because the Cardinals thought he could hit with consistent power and drive in runs. Instead, he finished fourth on the club in home runs (14) and sixth in RBI (45). A prime example of how Schoendienst put team ahead of individual occurred on July 22, 1968, when the Cardinals trailed the Phillies by two runs in the bottom of the ninth inning.

A prime example of how Schoendienst put team ahead of individual occurred on July 22, 1968, when the Cardinals trailed the Phillies by two runs in the bottom of the ninth inning. On Dec. 18, 2001, Martinez joined La Russa on the Cardinals.

On Dec. 18, 2001, Martinez joined La Russa on the Cardinals. On Dec. 9, 1931, the reigning World Series champion Cardinals acquired outfielder Hack Wilson and pitcher Bud Treachout from the Cubs for pitcher Burleigh Grimes.

On Dec. 9, 1931, the reigning World Series champion Cardinals acquired outfielder Hack Wilson and pitcher Bud Treachout from the Cubs for pitcher Burleigh Grimes. On Dec. 23, 2011, Beltran signed a two-year contract worth $26 million to be the Cardinals’ right fielder.

On Dec. 23, 2011, Beltran signed a two-year contract worth $26 million to be the Cardinals’ right fielder.