Cardinals pitcher Larry Jackson and Dodgers outfielder Duke Snider found out the hard way that bats and balls, like sticks and stones, may break bones.

On March 27, 1961, Jackson suffered a fractured jaw when Snider’s bat splintered and struck Jackson in the face during a spring training game.

On March 27, 1961, Jackson suffered a fractured jaw when Snider’s bat splintered and struck Jackson in the face during a spring training game.

Three weeks later, on April 17, 1961, Snider suffered a fractured right elbow when the Cardinals’ Bob Gibson hit him with a pitch during an at-bat in the regular season.

Gibson’s plunking of Snider had more to do with the home run Snider hit in his previous at-bat against Gibson than it did with the accident involving Jackson.

Jackson and Snider recovered from their injuries, and each went on to have a productive season.

Painful outing

Jackson was pitching in his last scheduled inning when Snider came to bat in the exhibition game between the Cardinals and Dodgers at Vero Beach, Fla.

Snider had hit a two-run home run in the first and a two-run double in the third against Jackson. In the sixth, with baserunner Tommy Davis on second, Snider was looking to drive in another run.

Jackson threw a pitch near Snider’s fists. Snider connected, shattering the bat and sending pieces of it flying. The ball hit Jackson on the hip and fell to the ground. As Jackson turned to retrieve it, the heavy end of the bat, whirling rapidly through the air, struck him in the lower left jaw.

“Bleeding from cuts inside his mouth, Jackson fell in a heap in front of the mound, but did not lose consciousness,” the Los Angeles Times reported.

In his book “The Duke of Flatbush,” Snider said, “I felt awful about it, but that’s one of the occupational hazards of pitching.”

Jackson was taken by ambulance to a Vero Beach hospital and given emergency treatment. X-rays showed he had two fractures in the jaw.

Jackson was permitted to return on a chartered flight to St. Petersburg, Fla., where the Cardinals trained. His jaw was wired that night by a surgeon at a St. Petersburg hospital.

Released from the hospital on March 31, Jackson pitched batting practice a few days later. The Cardinals targeted the end of April for his return in a game.

Purpose pitch

After the Cardinals opened the season with wins in three of their first five games, they started Gibson against the Dodgers at Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum.

In the third, Gibson threw a pitch on the outside corner to Snider, a left-handed batter. In the book “From Ghetto to Glory,” Gibson said, “I pitched away to Snider because he was a good pull hitter.”

In the third, Gibson threw a pitch on the outside corner to Snider, a left-handed batter. In the book “From Ghetto to Glory,” Gibson said, “I pitched away to Snider because he was a good pull hitter.”

Snider poked the ball over the screen in left for a two-run home run and a 3-1 Dodgers lead.

The next time Snider came up, in the fifth, “I was still going to pitch him outside,” Gibson said.

Gibson changed his mind when he noticed Snider lean in. “So I threw the next pitch tight to brush him back away from the plate,” Gibson said.

Snider barely saw the fastball. “It came right at me,” Snider said. “It was headed for my ribs and I brought up my right arm instinctively to protect my body. The pitch hit my elbow and the ball dropped straight to the ground. It was no glancing blow. It hit me flush.”

Snider advanced to first and was thrown out attempting to steal second.

When he tried to bat again in the seventh, Snider “felt a sharp pain in that right elbow, like someone jabbing a needle in there” and was lifted for a pinch-hitter.

An examination revealed the elbow was fractured.

“I saw Duke after the game,” Gibson said. “I didn’t apologize to him. He knew I was sorry. He knew I wasn’t throwing at him. I was trying to move him away from the plate, trying to get him to think and not take things for granted up there.”

In the book “We Would have Played For Nothing,” Snider told former baseball commissioner Fay Vincent, “I know that Bob Gibson has told people he never threw at a player on purpose. Bob Gibson is a nice guy, but he stretches the truth a little bit once in a while.” Boxscore

We meet again

Jackson’s absence from the starting rotation the first few weeks of the 1961 season was a significant setback for the Cardinals. The year before, he won 18 and led the National League in innings pitched (282).

A right-hander, Jackson made his first appearance of the 1961 season on April 26, a month after his injury, in a start against the Braves.

He lost his first three decisions, prompting The Sporting News to note, “After subsisting on liquids and soft foods for a month, Jackson showed he needed a few steaks to beef up his pitching.”

Meanwhile, after sitting out a month, Snider returned on May 19 as a pinch-hitter and was back in the Dodgers’ starting lineup on May 22.

Two days later, the Dodgers opened a series at St. Louis. Jackson started Game 1 and faced Snider for the first time since the spring training accident. Snider walked three times, but didn’t get a hit, and Jackson got his first win of the season. Boxscore

The next night, Gibson started and faced Snider for the first time since he suffered the fractured elbow. Snider got a single in four at-bats. Sandy Koufax pitched a three-hitter and Tommy Davis hit a home run in a 1-0 Dodgers triumph. Boxscore

Keep going

On June 26, Jackson lost to the Braves, sinking his record for the season to 3-8. Manager Solly Hemus dropped him from the starting rotation.

Two weeks later, Hemus was fired and Johnny Keane replaced him. Jackson returned to the rotation and won 11 of his next 12 decisions.

“There’s no pitcher in the league right now who’s better than Larry Jackson,” Keane said to the St. Louis Globe-Democrat.

Jackson finished the season at 14-11 with three shutouts and 211 innings pitched. He made six starts against the Dodgers and was 1-3. Snider hit .294 versus Jackson in 1961 and .219 for his career.

Snider finished the season with 16 home runs and a .296 batting mark. Against Gibson, Snider hit .300 in 1961 and .212 for his career.

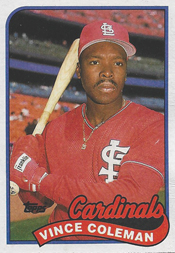

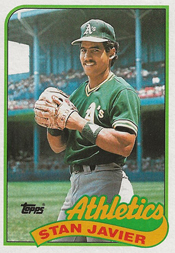

On March 26, 1981, Javier signed with the Cardinals as an amateur free agent.

On March 26, 1981, Javier signed with the Cardinals as an amateur free agent. On June 16, 1952, Thomson hit a grand slam in the bottom of the ninth, erasing a 7-4 Cardinals lead and lifting the Giants to an 8-7 victory at the Polo Grounds in New York.

On June 16, 1952, Thomson hit a grand slam in the bottom of the ninth, erasing a 7-4 Cardinals lead and lifting the Giants to an 8-7 victory at the Polo Grounds in New York. On March 3, 1981, the Cardinals signed Braun, a free agent, to a minor-league pact. A left-handed batter, Braun, 32, hoped to earn a spot with the Cardinals as a backup outfielder and pinch-hitter.

On March 3, 1981, the Cardinals signed Braun, a free agent, to a minor-league pact. A left-handed batter, Braun, 32, hoped to earn a spot with the Cardinals as a backup outfielder and pinch-hitter.