(Updated Nov. 25, 2024)

Ron Hunt, best known for getting hit by pitches, made his biggest contribution to the Cardinals just by standing still at the plate and watching a ball zip into the catcher’s mitt.

On Sept. 5, 1974, the Cardinals acquired Hunt, a second baseman, after the Expos placed him on waivers. Born and raised in St. Louis, Hunt got to close out his playing career in his hometown with the 1974 Cardinals.

On Sept. 5, 1974, the Cardinals acquired Hunt, a second baseman, after the Expos placed him on waivers. Born and raised in St. Louis, Hunt got to close out his playing career in his hometown with the 1974 Cardinals.

Adept at reaching base, Hunt was obtained to be a pinch-hitter who might ignite a spark for the Cardinals, contending for a division title.

Hunt did the job _ in eight plate appearances as a Cardinals pinch-hitter, he got on base five times (a .625 percentage), with two hits, two walks and one hit by pitch. Better yet, his patience at the plate enabled Lou Brock to break Maury Wills’ single-season stolen base record before the hometown fans.

Meet the Mets

Growing up in northeast St. Louis, Hunt considered himself a city kid before he moved with his mother and grandparents to nearby Overland. “My parents broke up when I was little,” Hunt said to Newsday. “My grandparents took care of me most of the time … They loved me so much they’d do anything for me.”

At Ritenour High School, Hunt was a third baseman and pitcher. He signed with the reigning National League champion Milwaukee Braves after graduating in June 1959. (Hunt’s favorite player, second baseman Red Schoendienst, helped the Braves win consecutive pennants in 1957-58.)

Assigned to play third base for the Class D team in McCook, Nebraska, Hunt, 18, was a teammate of pitchers Phil Niekro, 20, and Pat Jordan, 18. (Niekro went on to a Hall of Fame career and Jordan became a writer.)

Switched to second base in 1960, Hunt played three consecutive seasons in the minors for former Cardinals second baseman Jimmy Brown as his manager.

Late in the 1962 season, the Mets, on their way to losing 120 games, dispatched their coach, former Cardinals infielder and manager Solly Hemus, to scout prospects. After watching Hunt (.381 on-base percentage) play for Class AA Austin in the Texas League, Hemus recommended him to the Mets.

“I talked to Jimmy Brown about him,” Hemus told the New York Daily News. “He said he thought the kid could make the major leagues.”

In October 1962, the Mets purchased Hunt’s contract on a conditional basis. They had until May 9, one month after the start of the 1963 season, to decide whether to keep him or send him back to the Braves.

Gesundheit

Hunt appeared a longshot to make the leap from Class AA to the majors, but at 1963 spring training his rough and tumble style of play impressed manager Casey Stengel. “There’s a soft spot in the old man’s heart for his second baseman,” Newsday’s Joe Donnelly noted. “When he was a player, there must have been a bit of Ron Hunt in him.”

The 1963 Mets lost their first eight games before beating the Braves on Hunt’s two-run double in the ninth. Boxscore

Club owner Joan Payson showed her gratitude by sending a bouquet of roses to Hunt’s wife, Jackie, a gesture that prompted Hunt to run for a box of Kleenex.

“Ron is allergic to flowers,” Jackie told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

When he was a teen, “I went to an allergist,” Hunt said to the Los Angeles Times. “I found out I was allergic to just about everything.”

Hunt had asthma and, in addition to flowers, was allergic to two of the constant companions of an infielder _ grass and dust.

As St. Louis journalist Bob Broeg noted, Hunt “spends more time in the dirt than a grubworm.” Mets broadcaster Lindsey Nelson told Broeg, “My favorite recollection is of Ron sliding into second in a cloud of dust, coming up sneezing and borrowing umpire Augie Donatelli’s handkerchief to blow his nose.”

Hunt’s asthma and allergies required special attention. Mets trainer Gus Mauch kept under refrigeration a vial of medicine supplied by Hunt’s physician and administered the shots, the New York Daily News reported.

Neither his health issues nor the challenges of the big leagues deterred him. Hunt played with the same hustle, toughness and aggressiveness of another 1963 National League rookie second baseman, Pete Rose.

Bob Broeg described Hunt as “a back alley ballplayer.” Newsday’s George Vecsey observed that Hunt “slid hard with his spikes high and applied liberal dosages of knees to any runner who tried the same thing with him.”

“If anybody wants to get tough, I can get tougher than anybody else,” Hunt said to the Montreal Gazette.

On Aug. 6, 1963, the Cardinals’ Tim McCarver slid high and hard into Hunt at second base. McCarver’s spikes dug deep into Hunt’s thigh, causing two wounds. Hunt, hobbling, stayed in the game. Boxscore

Hunt led the 1963 Mets in total bases (211), hits (145), runs (64), doubles (28), batting average (.272) and most times hit by a pitch (13). He finished second to Rose in balloting for the National League Rookie of the Year Award.

Hit and run

In 1964, Hunt became the first Met to make the starting lineup for an All-Star Game. In voting by players, managers and coaches, Hunt was named the National League second baseman. He singled against Dean Chance in the game at New York’s Shea Stadium. Boxscore

(Hunt played in one other All-Star Game, in 1966 at St. Louis. His sacrifice bunt in the 10th inning moved Tim McCarver into position to score the winning run. Boxscore)

Hunt was sidelined for a chunk of the 1965 season because of a play involving the Cardinals’ Phil Gagliano. On May 11, with the bases loaded and one out, Lou Brock hit a slow grounder. Just as Hunt crouched for the ball, Gagliano, trying to advance from first to second, barreled into him. As Dick Young wrote in the lede to his story in the New York Daily News, “Ron Hunt was run over by an Italian sports car named Phil Gagliano.”

The impact separated Hunt’s left shoulder. He underwent an operation in which two metal pins were placed in the shoulder and was sidelined until August. Boxscore

In November 1966, Mets executive Bing Devine traded Hunt and Jim Hickman to the Dodgers for two-time National League batting champion Tommy Davis and Derrell Griffith. Hunt spent one season with the Dodgers, then went to the Giants (1968-70) and Expos (1971-74).

Black and blue

It was when he got to the Giants that Hunt began getting hit by pitches at an accelerated rate. He was the National League leader in most times getting plunked for seven consecutive seasons (1968-74).

Los Angeles Times columnist Jim Murray wrote, “Most batters dream of a pitcher they can hit. Hunt dreams of a pitcher who can hit him.”

Choking the bat up to the label, Hunt “couldn’t reach the ball unless two-thirds of his body was in the strike zone,” Jim Murray noted. Hunt told him, “I don’t stand close to the plate. I sit right on it.”

Hunt’s most remarkable seasons were with the Expos in 1971 (.402 on-base percentage, 145 hits, 58 walks, 50 hit by pitches) and 1973 (.418 on-base percentage, 124 hits, 52 walks, 24 hit by pitches).

On Sept. 29, 1971, when Hunt was plunked for the 50th time that season, the pitcher was the Cubs’ Milt Pappas, who told the Montreal Gazette, “He not only didn’t try to get out of the way, he actually leaned into the ball.” Pappas’ teammate, Ken Holtzman, said to the newspaper, “The pitch was a strike.” Boxscore

Hughie Jennings of the 1896 Baltimore Orioles holds the single-season record for most times hit by a pitch, with 51. Jim Murray wrote, “Hunt himself seems to go back to 1896. Crewcut, leather-faced, tobacco-chewing, his slight scarecrow appearance makes him look like something sitting with a squirrel gun and pointed black hat in front of an Ozark cabin.”

The pitcher who hit Hunt the most times with pitches was Bob Gibson (six). Tom Seaver and Nolan Ryan each plunked Hunt five times. In 1969, a Seaver fastball conked Hunt on the back of the batting helmet, knocking him out. The ball bounced high off his helmet and Seaver caught it near first base, according to the San Francisco Examiner. Taken off in a stretcher, Hunt was back in the lineup three days later. Boxscore

(As for Gibson, in a 2018 interview with Joe Schuster of Cardinals Yearbook, Hunt recalled, “When I was traded to the Cardinals, one day I was pitching batting practice to the pitchers and I must have thrown at Gibson 10 times, but as much as I tried, I couldn’t hit him once since he was jumping all over the place.”)

Helping hand

After the Cardinals acquired Hunt, their manager, Red Schoendienst, said to the Post-Dispatch, “He can help you win.”

Soon after, the Cardinals’ second baseman, Ted Sizemore, got injured when his spikes caught in a seam of the artificial turf while chasing a grounder. Hunt replaced him in the starting lineup.

Sizemore batted in the No. 2 spot, behind Lou Brock, and his patience in taking pitches enabled Brock to get a lot of stolen base attempts.

On Sept. 10, 1974, against the Phillies at St. Louis, Hunt, batting second, was at the plate when Brock stole two bases. The first was his 104th of the season, tying Maury Wills’ major-league mark. The second broke the record. Boxscore

Hunt, 34, went to spring training with the 1975 Cardinals, looking to earn a utility job. In the batting cage against the Iron Mike pitching machine, he got struck by pitches six times. Hunt “actually practiced getting hit by pitches,” Ira Berkow of the New York Times reported.

He didn’t do enough to get base hits, though, batting .194 in 12 spring training games, and was cut from the roster before the season began.

In 12 big-league seasons, Hunt had 1,429 hits, got plunked 243 times (Hughie Jennings is the leader with 287) and produced a .368 on-base percentage.

From his ranch in Wentzville, Mo., Hunt started a baseball program for youths ages 15 through 18. More than 100 of his players received college scholarships.

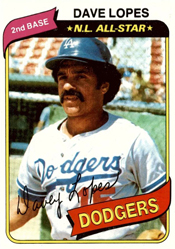

On Aug. 24, 1974, Lopes had five stolen bases for the Dodgers against the Cardinals. Watching him perform was the National League’s all-time best base stealer, the Cardinals’ Lou Brock.

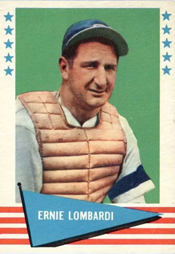

On Aug. 24, 1974, Lopes had five stolen bases for the Dodgers against the Cardinals. Watching him perform was the National League’s all-time best base stealer, the Cardinals’ Lou Brock. On July 6, 1934, the Reds edged the Cardinals, 16-15, at St. Louis. Lombardi, the Reds catcher and future Hall of Famer who was nicknamed “Schnozz” because of his big nose, produced five hits in five trips to the plate. Cardinals catcher

On July 6, 1934, the Reds edged the Cardinals, 16-15, at St. Louis. Lombardi, the Reds catcher and future Hall of Famer who was nicknamed “Schnozz” because of his big nose, produced five hits in five trips to the plate. Cardinals catcher  On July 1, 1984, the Cardinals and Expos swapped utility infielders, with Chris Speier coming to St. Louis for Mike Ramsey.

On July 1, 1984, the Cardinals and Expos swapped utility infielders, with Chris Speier coming to St. Louis for Mike Ramsey.

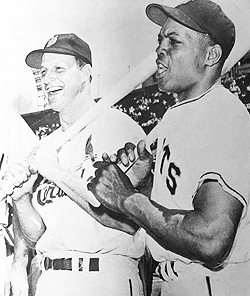

In June 1957, the Cardinals offered the New York Giants a combination of cash and players for Mays, the St. Louis Globe-Democrat reported.

In June 1957, the Cardinals offered the New York Giants a combination of cash and players for Mays, the St. Louis Globe-Democrat reported.