After he was graduated from Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, Walter Alston was ready to become a high school teacher. A knock on his door altered those plans.

Ninety years ago, in June 1935, Alston grabbed an opportunity to play professional baseball, signing a minor-league contract with the Cardinals.

Ninety years ago, in June 1935, Alston grabbed an opportunity to play professional baseball, signing a minor-league contract with the Cardinals.

The offer came from Frank Rickey, a Cardinals scout and brother of the club’s general manager, Branch Rickey. The day after Miami’s commencement ceremony, Alston was at home in tiny Darrtown, Ohio, when Frank Rickey surprised him with a rap on the door.

“Want to play pro baseball?” he asked.

In the book “Walter Alston: A Year at a Time,” Alston recalled to author Jack Tobin, “What a question to ask! I’d dreamed about that since I was old enough to throw that little rubber ball against the brick smokehouse out on our first farm.”

Alston went on to spend 10 seasons in the Cardinals’ system. He didn’t make it big as a player _ just one shaky appearance in a major-league game _ but it was the Cardinals who gave him the chance to manage in the minors.

That experience helped launch him into a long and successful career with the Dodgers that led to his election to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Hard work and patience

Alston was born on a small farm just north of Cincinnati, in Venice, Ohio. (Renamed Ross Township.) His father was a tenant farmer and stonemason. The family moved from farm to farm, wherever work was available, in southwest Ohio.

When Alston was a boy, his parents bought him a black Shetland pony. He named her Night. Alston rode the pony bareback to grade school in Ohio villages such as Camden and Morning Sun.

The family fell into debt when Alston was in seventh grade and moved to the hamlet of Darrtown. Alston’s father found work in nearby Hamilton at a Ford auto plant, producing wheels and running boards for $4 a day.

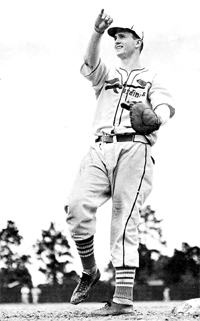

Alston developed a passion for baseball. His father taught him to throw with velocity. “Put some smoke on the ball,” he’d say. The youngster did it so well he got nicknamed “Smokey” and pitched in high school.

In May 1930, near the completion of his freshman year at Miami, Alston, 18, married his childhood sweetheart, Lela. The Great Depression had devastated the economy and Alston couldn’t afford to stay in college. He and Lela moved in with her parents in Darrtown and he took work wherever he could find it, going from farm to farm to seek pay for day labor. The county gave him a job cutting roadside weeds with a scythe. “That paid a dollar a day and I was happy to have it,” Alston told author Jack Tobin.

Two years later, in the summer of 1932, Alston still was whacking weeds when a local Methodist minister, Rev. Ralph Jones, an education advocate, urged him to return to Miami and earn a degree. According to author Si Burick in the book “Alston and the Dodgers,” Jones said to Alston, “Smokey, you’ve got a good mind. You can be somebody if you go back to college.”

Jones gave Alston $50 to use toward his tuition. Alston re-enrolled at Miami for the 1932 fall semester. “We never could have saved $50 on my dollar a day cutting weeds,” Alston told Jack Tobin. “That $50 … got me back in and paid a good part of my tuition for that year.”

Alston majored in industrial arts and physical education. He also played varsity baseball and basketball. There were no athletic scholarships and money was scarce. In between classes and athletics, Alston worked jobs on campus.

“I took a job driving a laundry truck for 35 cents an hour and I got my lunch free every day in exchange for racking up billiard balls in a pool hall,” he told journalist Ed Fitzgerald. “Summers, the college gave me a job painting dormitories.”

Alston played sandlot baseball for various town teams, too. One of those, the Hamilton Baldwins, had Alston at shortstop and Weeb Ewbank, the future football coach of the Baltimore Colts and New York Jets, in center field.

Cardinals prospect

Alston was taking an exam near the end of his senior year in 1935 when he was told someone was waiting to see him. It was Harold Cook, school superintendent in New Madison, Ohio. Cook was recruiting teachers and offered Alston a salary of $1,350 to come to New Madison. Alston accepted.

A few days later, Frank Rickey showed up at the door. (The Alstons didn’t have a home telephone then.) Rickey had seen Alston play two games _ one at shortstop and one as a pitcher _ for Miami and was impressed. When Alston mentioned he’d made a commitment to teach in New Madison, Rickey explained the minor-league season would be finished by Labor Day, enabling him to return to Ohio for the school year.

Rickey offered no signing bonus. He told Alston, 23, he’d be paid $135 a month to play in the Cardinals’ system that summer. Alston signed on the spot.

The next day, Alston’s wife drove him to Richmond, Ind., where he boarded a bus for St. Louis. Upon arrival, Alston checked into the YMCA downtown. The next morning, he went to the Cardinals’ offices to find out where he was being assigned. The Cardinals told him to come back tomorrow. This went on for a week until, finally, Branch Rickey informed Alston he would play for the Greenwood (Mississippi) Chiefs of the East Dixie League.

Cardinals scout Eddie Dyer (who, years later, became St. Louis manager) drove Alston from St. Louis to Mississippi in a roadster. Player-manager Clay Hopper put Alston at third base and he hit .326 in 82 games.

Every fall and winter for the next 14 years, Alston taught high schoolers _ six years at New Madison and eight at Lewiston, Ohio _ in order to make ends meet after spending spring and summer in the minors. He taught industrial arts, general science and biology, and coached basketball before leaving in March for spring training.

The teaching experience later helped him as a manager. “Like students, ballplayers can’t all be treated the same,” Alston told Si Burick. “Some need encouragement. Some do better if left alone. Others need to be driven. You simply have to study each individual and get him to produce the best that’s in him.”

Darrtown remained Alston’s home. Los Angeles Times columnist Jim Murray described it as “the place where time forgot” and “where the 11 o’clock news is the barber.” Alston built a house at the corner of Apple and Cherry streets. It was the first brick house in Darrtown. “My dad laid all the bricks and mixed the mortar,” he told Sports Illustrated.

In the backyard tool shed, Alston put his industrial arts skills to good use, making most of the furniture for his house. “His bookshelves and chests and spice racks and desks are a wonder of patient, meticulous workmanship,” Sheldon Ocker of the Akron Beacon-Journal reported.

When he wasn’t woodworking, Alston enjoyed skeet shooting, riding his two Honda motorcycles and playing billiards.

After Alston became an established big-league manager, billiards legend Willie Mosconi was a guest at Alston’s Darrtown home, where Alston had a pool table. “I ran 47 balls, which is pretty good for me,” Alston told Gordon Verrell of the Long Beach Press-Telegram. “He shot, made six or seven and missed, and then I ran 10 or 12. I didn’t get another shot. He ran the next 154.”

Alston didn’t mind losing to a master such as Mosconi. Getting defeated by Cardinals pitcher Steve Carlton in 1969 was another matter. “He beat us 1-0 that night at the ballpark and, if that didn’t make me mad enough, he beat me later that night in a game of pool,” Alston told Gordon Verrell. Boxscore

Ready or not

For his second season in the Cardinals’ system in 1936, Alston was assigned to Huntington, W.Va. Player-manager Benny Borgmann taught him to play first base. The club’s shortstop was a skinny teenage rookie, Marty Marion.

For the second consecutive year, Alston hit .326. He also produced 35 home runs and 114 RBI. Scout Branch Rickey Jr., son of the Cardinals’ general manager, was impressed. On Rickey Jr.’s recommendation, Alston was called up to the Cardinals in September and instructed to join the team in Boston.

Alston packed a beat-up cardboard suitcase and took a train to New York City, where he was to make a connection to Boston. At Grand Central Station, he was gawking at the ceilings and the people when he bumped into a woman. “The suitcase hit the floor, broke open and scattered all my clothes and belongings across the floor,” he recalled to Jack Tobin. “There seemed to be hundreds and hundreds of people all racing in a different direction. I was on my hands and knees, trying to pick up my shirts and shorts … and to keep from being trampled.”

A Good Samaritan directed him to a luggage shop nearby. Alston spent most of the $20 he had on a new suitcase and boarded the train to Boston.

When he arrived at the Kenmore Hotel, the team was at the ballpark. The desk clerk told Alston he could go to the dining room and sign for anything he ordered. “One look at the menu convinced me I was in for a hard time,” Alston told Jack Tobin. “I had never heard of half the things and couldn’t pronounce most of the words … Finally I decided on some clams. I’d always heard Boston was famous for them. When they brought them out, I wasn’t sure just how you were supposed to eat them.”

During his month with the Cardinals, Alston pitched batting practice, took infield practice with other rookies and otherwise sat on the bench. A fellow Ohioan, pitcher Jesse Haines, 43, took a liking to Alston, 24, and showed him what to do and how to do it. “No matter what I asked, he knew the answer,” Alston said to Jack Tobin. “Most days he took me to and from the ballpark. He was my buddy.”

Put me in, coach

On the final day of the season, the Cardinals played at home in the rain against the Cubs. Plate umpire Ziggy Sears had a miserable time. Neither team cared for the way he called balls and strikes. Sears ejected Cardinals coach Buzzy Wares and Cubs manager Charlie Grimm for arguing with him.

As the Cardinals came off the field in the seventh, first baseman Johnny Mize made a remark while passing the umpire. Offended, Sears ejected Mize.

Because the Cardinals’ other established first baseman, Rip Collins, had been used as a pinch-hitter a couple of innings earlier, manager Frankie Frisch had to go with his only other first baseman, Alston.

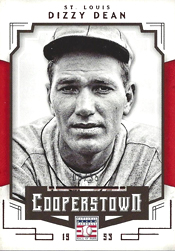

When the Cubs batted against Dizzy Dean in the eighth, Alston was at first, making his big-league debut. Augie Galan led off with a single. Phil Cavarretta followed with a bunt. Third baseman Don Gutteridge fielded cleanly and made an accurate throw to Alston, but the first baseman bobbled the ball. Cavarretta reached safely on the error and Galan stopped at second.

Next up was Billy Herman. He bunted toward Alston. The rookie threw to third, but not in time to nab Galan, and the bases were loaded. All three runners eventually scored, giving the Cubs a 6-1 lead.

In the ninth, the Cardinals scored twice and had a runner on base, with two outs, when Alston batted for the first time. The pitcher was Lon Warneke, a three-time 20-game winner. Alston fouled off a pitch. He ripped another down the line in left but it, too, curved foul near the pole. Then he struck out, ending the game. Boxscore

The next day, the headline in the St. Louis Star-Times blared, “Walter Alston Makes Blunders That Eventually Beat Dizzy Dean, 6-3.”

Follow the leader

The Cardinals put Alston on their 40-man winter roster, but Johnny Mize still was on the team and the club acquired another first baseman, Dick Siebert, from the Cubs. Because of his teaching job, Alston couldn’t report to 1937 spring training until March 15. A couple of weeks later, he was back in the minors.

Alston had a few more good seasons in the Cardinals’ system, but knew he likely wouldn’t be returning to the big leagues. “I had enough power, but … I couldn’t hit the good pitching, just the mediocre pitching,” he told Sports Illustrated.

Branch Rickey asked Alston to become a player-manager in 1940 and he eagerly accepted. Alston managed Cardinals affiliates for three seasons (1940-42). Then Rickey moved to the Dodgers. Alston kept playing for Cardinals farm teams desperate to fill rosters depleted by World War II military service.

In 1944, Alston was released by the Cardinals. He returned to Darrtown, figuring to go fulltime into teaching. Then came another bang on the door. It was the son of the man who operated the Darrtown general store. The boy told Alston there was an urgent long-distance phone call for him at the store. Alston darted the two blocks, grabbed the receiver and heard the voice of Branch Rickey.

“First thing he did was give me a good going over for not having a phone and told me to get one,” Alston said to Jack Tobin. “Then he offered me the manager’s job at Trenton (N.J.) in the Interstate League.”

Alston managed for 10 seasons in the Dodgers’ system. In November 1953, he was chosen to replace Chuck Dressen as Dodgers manager. Working on one-year contracts, Alston managed the Dodgers for 23 years, leading them to seven National League pennants and four World Series titles. He was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1983.

As Jim Murray wrote, “He made his profession’s hall of fame not because he could hit or throw a curveball better than anyone else but because he excelled in the far more difficult area of human endeavor.”

On June 4, 1935, at Pittsburgh, the St. Louis ace experienced an unlucky inning against the Pirates. Dean blamed the umpire and the Cardinals fielders. An argument ensued in the dugout and it nearly led to a fight.

On June 4, 1935, at Pittsburgh, the St. Louis ace experienced an unlucky inning against the Pirates. Dean blamed the umpire and the Cardinals fielders. An argument ensued in the dugout and it nearly led to a fight. One hundred years ago, on May 30, 1925, Breadon changed managers, replacing Rickey with

One hundred years ago, on May 30, 1925, Breadon changed managers, replacing Rickey with  A pair of catchers, Del Rice of the Cardinals and Rube Walker of the Dodgers, were the contestants in what Bob Broeg of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch described as “a snail versus tortoise match race.”

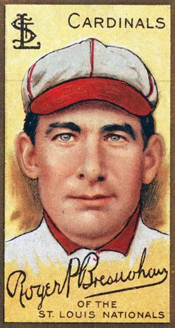

A pair of catchers, Del Rice of the Cardinals and Rube Walker of the Dodgers, were the contestants in what Bob Broeg of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch described as “a snail versus tortoise match race.” Bresnahan, the Cardinals’ player-manager in 1911, would become the second catcher (after Buck Ewing) elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Yet, when the Cardinals were in a pinch at second base, Bresnahan inserted himself there in a game against the Pirates.

Bresnahan, the Cardinals’ player-manager in 1911, would become the second catcher (after Buck Ewing) elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Yet, when the Cardinals were in a pinch at second base, Bresnahan inserted himself there in a game against the Pirates. Invited to try out for a spot as an outfielder on the 2008 Cardinals, Gonzalez was Juan Gone _ as in, headed home _ before spring training ended.

Invited to try out for a spot as an outfielder on the 2008 Cardinals, Gonzalez was Juan Gone _ as in, headed home _ before spring training ended.