Though the minor leagues were where Gaylen Pitts spent most of his long and accomplished baseball career, he twice reached the majors _ and both times with the help of Dal Maxvill.

Pitts was a player, manager, coach and instructor in the minors, primarily with the Cardinals.

Pitts was a player, manager, coach and instructor in the minors, primarily with the Cardinals.

An infielder, he played 13 years in the farm systems of the Cardinals, Athletics and Cubs. He managed in the minors for 19 years for the Cardinals, A’s and Yankees.

Pitts got to the big leagues with the A’s for the first time in 1974 as an infield replacement for Maxvill, who got injured. Then, after the 1990 season, it was Maxvill, the Cardinals’ general manager, who recommended Pitts for the role of bench coach on the staff of manager Joe Torre.

Down on the farm

Pitts moved with his family from Wichita, Kan., to Mountain Home, Ark., when he was a boy. He listened to Cardinals games on the radio, played baseball in high school and caught the attention of scout Fred Hawn, who arranged for a tryout in St. Louis. Pitts was 18 when the Cardinals signed him for $8,000 in 1964. “I bought a car; a good one,” he recalled to the Arkansas Democrat Gazette.

Early in the 1966 season, Pitts was drafted into the Army and served in Vietnam. He returned to baseball in 1968. Two years later, Pitts, a utility infielder candidate, got invited to the Cardinals’ big-league spring training camp for the only time. He didn’t make the club, but he did become pals with the Cardinals’ shortstop, Dal Maxvill, Pitts recalled to the Society for American Baseball Research.

“When I was with the Cardinals, they wanted only veteran players,” Pitts told the Wichita Beacon. “If something went wrong with the big club, they’d go out and trade or buy a veteran. When they started their youth movement, I was traded.”

During the 1971 season, his seventh in the Cardinals’ farm system, Pitts was dealt to the A’s for Dennis Higgins, and sent to Class AAA Iowa, where he took the place of another veteran infielder, Tony La Russa, who got called up to Oakland.

Pitts never hit .300 in the minors. His single-season career highs in home runs (12) and RBI (58) were not robust. His hope for reaching the majors came from his ability to play multiple infield positions (second, short and third).

In May 1974, 10 years after he started out in the minors, Pitts got the call. With A’s second baseman Dick Green and third baseman Sal Bando sidelined because of injuries, Maxvill, their reserve infielder, got hurt. Needing someone who could fill in at multiple spots, the A’s promoted Pitts.

That’s a winner

When Pitts arrived in Oakland, Maxvill’s name was marked above the locker he was given, indicating the club didn’t expect the 27-year-old rookie to be around long. Nonetheless, his teammates “treated me great, from Catfish Hunter to Reggie Jackson,” Pitts recalled to the Memphis Commercial Appeal.

A highlight came on May 14, 1974, at Oakland against the Royals when Pitts drove in both runs with doubles in a 2-1 victory for the A’s.

Facing Lindy McDaniel, the 38-year-old former Cardinal _ “I used to follow him when I was a kid,” Pitts told the Oakland Tribune _ Pitts drove in Angel Mangual from second with a double in the fifth.

With the score tied at 1-1 in the 10th, Ted Kubiak was on first, one out, when Pitts lined a McDaniel slider over the head of left fielder Jim Wohlford. Kubiak slid around catcher Fran Healy to score just ahead of the relay throw and give the A’s a walkoff win.

Ron Bergman of the Oakland Tribune wrote of Pitts’ game-winning double, “He put some cream in his major league cup of coffee.”

Pitts told the newspaper, “I’ll remember this no matter what happens.” Boxscore

A month later, Pitts was back in the minors. He returned to the A’s in September 1975 and got three at-bats, his last as a big leaguer.

Follow the leader

After playing his final season in the minors in 1977, Pitts was named manager of an A’s farm club at Modesto, Calif. On a salary of $8,000, he couldn’t afford a car, so he rode a bicycle back and forth from his residence to the ballpark.

Recalling that first season as manager, Pitts told the Modesto Bee, “They say you learn from your mistakes, and I want to tell you, I did a lot of learning.”

After two years with Modesto, Pitts rejoined the Cardinals and spent 16 seasons managing their farm clubs. In other years with them, he was special assistant for player development, minor league field coordinator and a coach on the staff of Louisville manager Jim Fregosi.

“I’ve picked up a little from every manager I’ve ever played for or worked with,” Pitts told the Louisville Courier-Journal, “but I probably learned the most with Fregosi, not just on the field, but off the field, too.”

(According to the Courier-Journal, in 1990, when Pitts was Louisville manager, the team was waiting in the Denver airport for a flight when he struck up a conversation with a woman. They hit it off and eventually married.)

Among the Cardinals prospects Pitts managed were Rick Ankiel, Allen Craig, Daniel Descalso, J.D. Drew, Bernard Gilkey, Jon Jay, Ray Lankford, Joe McEwing, Adam Ottovino, Placido Polanco and Todd Zeile. Pitts also managed Andy Van Slyke and later Andy’s son, A.J. Van Slyke.

Future big-league managers who were managed by Pitts included Terry Francona, Oliver Marmol and Jim Riggleman.

“I’m really impressed with the job that Gaylen does,” Tony La Russa, the Cardinals’ manager, said to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch in 2000.

In describing Pitts as a manager who stressed fundamentals, Don Wade of the Memphis Commercial Appeal noted, “Pitts was old school before old school was retro. He’s brick foundation old school, not prefab.”

Regarding his managing style, Pitts told the Courier-Journal, “You’ve got to know when to bark and when not to. It’s just mutual respect. There’s a fine line there.”

Pitts briefly left the Cardinals’ organization. In 2003, he was the hitting coach on the staff of manager Cecil Cooper at Indianapolis, a Brewers farm team. Noting that Cooper had 2,192 big-league hits and Pitts had 11, the Post-Dispatch suggested the roles should be reversed. Pitts said with a laugh, “Cecil told me he would help me with the hitting stuff if I would help him with the managing.”

In 2006, Pitts managed a Yankees farm club, Staten Island, to the championship of the New York-Pennsylvania League.

Cardinals candidate

After Cardinals manager Whitey Herzog quit the team in July 1990, general manager Dal Maxvill interviewed seven candidates for the job: Don Baylor, Pat Corrales, Mike Jorgensen, Hal Lanier, Gene Tenace, Joe Torre and Pitts, according to the Post-Dispatch. (Ted Simmons removed himself from consideration.)

Noting that Pitts “has done a good job developing talent for the Cardinals,” columnist Bernie Miklasz wrote that Pitts would be “in over his head” as Cardinals manager because he “doesn’t have any experience working with major league players.” Miklasz suggested Pitts “needs to become a major league coach first to receive the needed exposure.”

Maxvill hired Torre in August 1990. After the season, Torre chose Pitts for his coaching staff on the suggestion of Maxvill, Pitts told researcher Gregory H. Wolf.

Pitts was Torre’s bench coach from 1991-94 and third-base coach in 1995.

When Torre was fired in June 1995 by Maxvill’s replacement, Walt Jocketty, Pitts and fellow coach Chris Chambliss were considered for the role of interim manager, but the job went to the club’s director of player development, Mike Jorgensen.

According to the Post-Dispatch, Jocketty said Pitts and Chambliss “were very qualified to manage, but I wanted to bring in someone who could change the dynamics a little … someone familiar with the situation, yet who was not there on the front line every day.”

Though he never got the chance to manage in the majors, Pitts told the Baxter (Ark.) Bulletin in 2004, “For a country boy from Arkansas who had never been out of Mountain Home much before I got out of high school, I’ve had a great ride.”

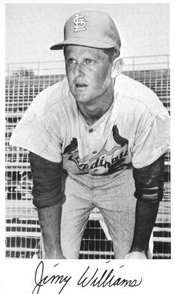

A middle infielder whose professional baseball experience consisted of one season at the Class A level of the minors, Williams got his first at-bat in the majors against none other than Sandy Koufax. His second plate appearance also came against a future Hall of Famer, Juan Marichal.

A middle infielder whose professional baseball experience consisted of one season at the Class A level of the minors, Williams got his first at-bat in the majors against none other than Sandy Koufax. His second plate appearance also came against a future Hall of Famer, Juan Marichal. Yet, the 1982 Cardinals may be the franchise’s greatest team since baseball went to a divisional alignment. Since 1969, the only Cardinals club to finish a regular season with the best record in the National League and win a World Series title was the 1982 team.

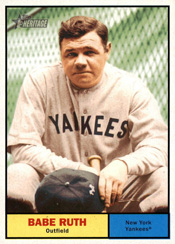

Yet, the 1982 Cardinals may be the franchise’s greatest team since baseball went to a divisional alignment. Since 1969, the only Cardinals club to finish a regular season with the best record in the National League and win a World Series title was the 1982 team. After finishing last in the eight-team American League in 1937, the Browns were looking for a manager and Babe Ruth wanted the job.

After finishing last in the eight-team American League in 1937, the Browns were looking for a manager and Babe Ruth wanted the job. What Donovan needed more than the luck of the Irish was a dugout full of run producers and premium pitchers.

What Donovan needed more than the luck of the Irish was a dugout full of run producers and premium pitchers.