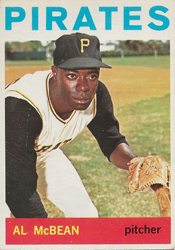

Stan Musial and Red Schoendienst had a high regard for Pirates pitcher Al McBean; so much so that there was talk of a swap involving him and Curt Flood.

A right-hander from the Virgin Islands who pitched 10 years (1961-70) in the majors, McBean was a good pitcher (67-50, 63 saves) who was as effective with a bat as he was with his arm against the Cardinals.

A right-hander from the Virgin Islands who pitched 10 years (1961-70) in the majors, McBean was a good pitcher (67-50, 63 saves) who was as effective with a bat as he was with his arm against the Cardinals.

McBean twice hit home runs in wins versus the Cardinals. In turn, the Cardinals used home runs to beat him. The most striking example came in 1964 when McBean was as good as any reliever in the National League. He yielded a mere four home runs that season _ and all were hit by Cardinals.

A sinkerball specialist with a showman’s flair, McBean struck out more Cardinals (92) than he did any other foe, but his record against them was 6-8.

Picture this

McBean played baseball as a youth on St. Thomas, one of the U.S. Virgin Islands, but had no plans to become a pro. When he finished his schooling, he worked as a photographer for a local daily newspaper, The Home Journal. “I only played ball on Sundays because there was nothing else to do on Sundays,” he recalled to columnist Larry Merchant.

The Pirates held a tryout camp on St. Thomas and McBean’s newspaper assigned him to cover it. A former coach saw him and encouraged McBean to join the prospects on the diamond. According to the Philadelphia Daily News, McBean was sent to center field, told to throw a ball toward home plate and delivered a missile. Then he was instructed to try it from the mound. The Pirates liked what they saw and signed him.

McBean, 20, began his pro career in the Pirates’ farm system in 1958. Three years later, in July 1961, he got called up to the big leagues and pitched in relief for the reigning World Series champions.

In a game against the Cardinals that season, the rookie gave up a grand slam to Bill White. The towering drive carried to the back of the screen on the pavilion roof at St. Louis. (White would torment McBean throughout his career, hitting .440 with four home runs against him.) Boxscore

Two weeks later, Stan Musial slugged a two-run homer versus McBean. Boxscore

Overall, though, McBean (3-2, 3.75) showed enough for the Pirates to put him in their plans for 1962.

Bold buccaneer

With Joe Gibbon and Vern Law having arm ailments in 1962, the Pirates moved McBean into the starting rotation. He delivered a 15-10 record, including 3-1 versus the Cardinals.

McBean got married in Pittsburgh during that 1962 season. Serving as best man at the wedding was his road roommate, Roberto Clemente.

McBean embraced the spotlight _ both on and off the field.

A lithe (165-pound) athlete, McBean’s voice had “the lilt of a calypso melody and is as bouncy as a bongo,” according to Milton Gross of the North American Newspaper Alliance.

McBean wore clothes designed for attention. A purple suit. A white Nehru jacket. Or, as Milton Gross described, “The large red bandana he pulls from his hip pocket to wipe his face on the mound is only a pale reflection of his vivid personality. He may, for instance, be seen coming to or leaving the ballpark clothed in an ascot, a Rex Harrison (houndstooth) hat, red vest, canary yellow shirt, dark sports jacket, checked pants and a rolled umbrella swinging from his arm.”

His flashy style wasn’t limited to his wardrobe.

Before games, McBean put on shows during infield practice, scooping grounders with behind-the-back moves. “He makes an infield drill look like a Harlem Globetrotters warmup with his uncanny fielding style and non-stop chatter,” Bill Conlin of the Philadelphia Daily News observed.

Red Schoendienst said to the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, “Funniest guy I’ve ever seen in a uniform. McBean is full of fun, especially before a game in practice.”

In his prime years, when he went back to being a reliever, McBean walked from the bullpen to the mound with a swagger.

“McBean saunters into a game,” Pirates manager Danny Murtaugh said to the Philadelphia Daily News.

Columnist Stan Hochman wrote, “He sashays out of the bullpen.”

Or, as Pittsburgh Courier sports editor Bill Nunn Jr. noted, “If one envisions a rooster strutting, you have McBean’s walk. The swaying of his fanny is the equal to the backlash generated by most show girls. His quick gait does justice to a fancy-stepping drum major.”

One time, when he got called into a 1963 game, McBean reached the mound, handed his sunglasses to the bat boy, then sent him to the dugout for a different shade of glove, according to columnist Stan Hochman.

“He wants to be noticed,” Pirates general manager Joe Brown said to the North American Newspaper Alliance. “He does things to be seen. He’s an individualist who doesn’t want to stay in a mold. Everything he does, he wants to be different _ his clothes, his windup, the way he walks, the way he talks. He’s like a faucet. Turn him on and he goes until you turn him off.”

Trading places

McBean had the stuff to back up his struts.

He was 13-3 with 11 saves in 1963 and 8-3 with 21 saves and a 1.91 ERA in 1964. “He’s good, all right, and he’s cocky, too, but he gets the job done,” Cubs slugger Ron Santo said to The Pittsburgh Press. “McBean is as fast as anybody in the league. He just throws the ball right by you.”

From late July 1963 to mid August 1964, McBean pitched in 62 games for the Pirates without a defeat, totaling 11 wins and 19 saves.

He threw from a variety of arm angles and his pitches darted in a maze of directions. One year, when McBean struggled, his manager, Larry Shepard, advised him to quit trying to be so precise with location of his pitches. “I told him to throw the ball down the middle,” Shepard recalled to the Philadelphia Daily News. “The way his ball moves, there’s no way he can throw a strike down the middle anyway. So why try to hit the corners?”

According to the Pittsburgh Courier, Stan Musial described McBean as a “pitcher who moves the ball around on every pitch.”

Al Abrams of the Pittsburgh-Post Gazette wrote that Musial and Schoendienst “persisted for years in asking, ‘What’s a guy with Al McBean’s pitching talent doing in the bullpen?’ They would have loved to have had him pitch for the Cardinals. They almost did.”

In June 1967, when the Cardinals had Musial as general manager and Schoendienst as manager, the Pirates offered to trade McBean, outfielder Manny Mota and catcher Jim Pagliaroni to St. Louis for outfielder Curt Flood, reliever Hal Woodeshick and catcher Johnny Romano, The Sporting News reported.

The Pirates “came close” to making the deal, but “word is that Cardinals owner Gussie Busch vetoed the trade at the last minute,” according to the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

Muscling up

At the plate, McBean usually swung with all his slender might (in 1962, for instance, he struck out 32 times in 67 at-bats), but when he connected the ball could carry.

On June 16, 1963, at St. Louis, the score was tied at 3-3 in the 12th inning when McBean faced Ed Bauta and walloped a 400-foot home run halfway up the bleachers in left.

“Nobody believes me when I say I’m a good hitter,” McBean said to The Pittsburgh Press, “but when Ed Bauta gave me what I like _ a high, slow curve _ I almost jumped. This was right down my alley.”

In addition to his home run, McBean pitched six innings of scoreless relief and got the win. Boxscore

Five years later, in a 1968 game against the Cardinals at Pittsburgh, McBean hit a grand slam against Larry Jaster in a 7-1 Pirates victory. The Cardinals collected 13 hits and a walk against McBean but stranded 12 runners and hit into two double plays. Boxscore

In 1964, when McBean pitched in 58 games, the only team to hit home runs against him was St. Louis. Bill White hit two and Ken Boyer and Lou Brock had one apiece. Brock’s was a walkoff shot _ his first in the majors _ in the 13th inning. It landed on the right field roof and gave the Cardinals a 7-6 victory.

“He gave me a high, inside fastball and I jumped on it,” Brock told The Pittsburgh Press. “It was too good to be true.” Boxscore

For his career, Brock hit .476 with three home runs against McBean.

Some other future Hall of Famers didn’t fare as well. Hank Aaron batted .176 with one home run versus McBean and had more strikeouts (10) than hits (nine) against him. In 57 at-bats versus McBean, Ernie Banks hit .175 with no homers.

In 1967, after Jim Lonborg’s one-hitter versus St. Louis in World Series Game 2, Brock told the Boston Globe, “He had darn good stuff, but he’s not a (Juan) Marichal or a (Gaylord) Perry. He doesn’t even have the speed of Al McBean.”

Sewell went hunting with a group in Florida’s Ocala National Forest on that day, the last of deer season.

Sewell went hunting with a group in Florida’s Ocala National Forest on that day, the last of deer season. Doing the unexpected came naturally to MacKenzie. A hockey player from a small town on a Canadian island, he went to Yale, graduated and became a big-league pitcher.

Doing the unexpected came naturally to MacKenzie. A hockey player from a small town on a Canadian island, he went to Yale, graduated and became a big-league pitcher. In the 1940s, the Cardinals (four) and Dodgers (three) won seven of the 10 National League pennants that decade. Casey was a prominent pitcher on the Dodgers championship clubs in 1941 (14 wins, seven saves) and 1947 (10 wins, 18 saves).

In the 1940s, the Cardinals (four) and Dodgers (three) won seven of the 10 National League pennants that decade. Casey was a prominent pitcher on the Dodgers championship clubs in 1941 (14 wins, seven saves) and 1947 (10 wins, 18 saves).