(Updated Sept. 12, 2024)

Jack Hamilton was a hard-throwing Cardinals pitching prospect who left the organization after four seasons and went on to experience his best major-league moments against them.

Hamilton is most remembered as the pitcher who in 1967 beaned Red Sox slugger Tony Conigliaro, fracturing his cheekbone, dislocating his jaw and severely damaging his left eye.

Hamilton is most remembered as the pitcher who in 1967 beaned Red Sox slugger Tony Conigliaro, fracturing his cheekbone, dislocating his jaw and severely damaging his left eye.

Though wildness plagued him throughout his professional baseball career, Hamilton was capable of dominating a game. With the Mets in 1966, he pitched a one-hitter against the Cardinals. A year later, he surprised the Cardinals with his bat, hitting a grand slam.

Wild Thing

Hamilton, 18, attended a Cardinals tryout camp at Busch Stadium in St. Louis in 1957 and impressed. “There were a lot of kids there, but I believe only two of us signed contracts,” Hamilton said to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

The Cardinals gave Hamilton a $4,000 bonus and assigned him to Wytheville, Va., a Class D club in the Appalachian League. Hamilton posted a 7-0 record for Wytheville and pitched a no-hitter in a game scheduled for seven innings.

After that, though, he was erratic in pitching for other Cardinals farm clubs. Hamilton was 12-16 for Keokuk, Iowa, in 1958 and 6-10 for York, Pa., in 1959.

Assigned to Class AA Memphis in 1960, Hamilton was chosen by manager Joe Schultz to be the Opening Day starter against Nashville. “He shut them out for four innings and then he went wild,” Schultz said. “He kept hitting the backstop and a couple of balls almost hit my catcher, Tim McCarver, on the head.”

The Cardinals demoted Hamilton to the Class B Winston-Salem Red Birds and he was 6-9 with a 4.33 ERA. Despite an exceptional fastball _ “He could throw a ball through a brick wall,” said Cardinals icon Red Schoendienst _ Hamilton wasn’t protected on the St. Louis roster and he was chosen by the Phillies in the November 1960 minor-league draft.

“Jack always could throw hard, but he was too wild,” Schultz said.

Beware the bunt

Hamilton, a right-hander, got to the majors with the Phillies in 1962 and the rookie led the National League that season in walks (107) and wild pitches (22).

After stints with the Phillies (1962-63) and Tigers (1964-65), Hamilton landed with the Mets in 1966. “Spitball Jack, a card shark,” Mets first baseman Ed Kranepool told Dave Anderson of the New York Times. “He liked poker. He beat all of us young guys.”

On May 4, 1966, Hamilton started for the Mets against the Cardinals at St. Louis and was opposed by Ray Sadecki. Hamilton and Sadecki became friends when both were in the Cardinals’ minor-league system.

Hamilton held the Cardinals to one hit over nine innings in an 8-0 Mets triumph. The lone St. Louis hit was a bunt single by Sadecki with two outs in the third.

With the count at 1-and-1, Sadecki pushed a bunt toward the third-base side of the infield. “A bunt was the furthest thing from my mind in the third inning,” said Mets third baseman Ken Boyer, the former Cardinal.

Hamilton told The Sporting News, “He (Sadecki) caught me flat-footed.”

After the game, Sadecki came into the Mets’ clubhouse and congratulated Hamilton. “Ray and I … were old buddies,” Hamilton said. “He told me he was sorry he got the hit. I ribbed him about that, telling him how much money he cost me by preventing me from pitching a no-hitter.” Boxscore

Hard to believe

A year later, on May 20, 1967, Hamilton, a .107 career hitter in the big leagues, hit his only home run, a grand slam off the Cardinals’ Al Jackson in the second inning. Hamilton, however, yielded four runs in three innings and the Cardinals came back for an 11-9 victory over the Mets at New York. Boxscore

“We get the Cardinals games clear on radio from St. Louis to our home in Burlington, Iowa,” Hamilton said, “and my wife said right after I hit the home run she must have got 10 phone calls asking if it was really true.”

A month later, the Mets traded Hamilton to the Angels. He was 9-6 with a 3.24 ERA for the 1967 Angels, but his peformance was marred by the beaning of Conigliaro in August that year.

Hamilton, often accused of throwing a spitball, finished his major league career in 1969 with the Indians and White Sox. His big-league totals include a 32-40 record, 20 saves and almost as many walks (348) as strikeouts (357).

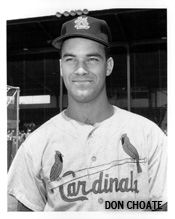

Instead, Choate went to the Giants in the trade that brought

Instead, Choate went to the Giants in the trade that brought  In 1942, Staley was in his second season as a pitcher for the Boise (Idaho) Pilots of the Class C Pioneer League. Boise wasn’t affiliated with any major-league organization.

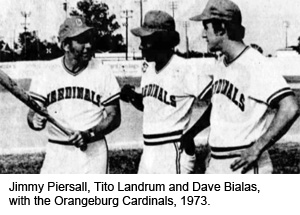

In 1942, Staley was in his second season as a pitcher for the Boise (Idaho) Pilots of the Class C Pioneer League. Boise wasn’t affiliated with any major-league organization. The man who hired Piersall to manage the Orangeburg (S.C.) Cardinals in 1973 didn’t know the former big-league outfielder was being treated for a mental health issue at that time, though Piersall’s history certainly was no secret. In 1952, while playing for the Red Sox, Piersall suffered a nervous breakdown. He wrote a book, “Fear Strikes Out,” about that experience and Hollywood made it into a film, starring Anthony Perkins.

The man who hired Piersall to manage the Orangeburg (S.C.) Cardinals in 1973 didn’t know the former big-league outfielder was being treated for a mental health issue at that time, though Piersall’s history certainly was no secret. In 1952, while playing for the Red Sox, Piersall suffered a nervous breakdown. He wrote a book, “Fear Strikes Out,” about that experience and Hollywood made it into a film, starring Anthony Perkins. In 1960, Donohue, a St. Louis native and graduate of Christian Brothers College High School, made a strong bid for a spot on the Cardinals’ Opening Day roster, but fell short of achieving the goal.

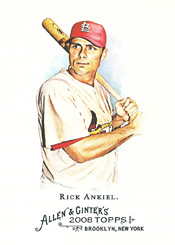

In 1960, Donohue, a St. Louis native and graduate of Christian Brothers College High School, made a strong bid for a spot on the Cardinals’ Opening Day roster, but fell short of achieving the goal. On Aug. 9, 2007, Ankiel returned to the big leagues with the Cardinals after a three-year absence.

On Aug. 9, 2007, Ankiel returned to the big leagues with the Cardinals after a three-year absence.