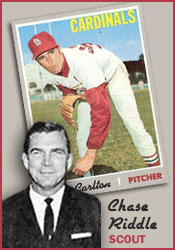

Chase Riddle never played a game for the Cardinals, but he had a major impact on the makeup of their teams.

Riddle was the scout who signed pitcher Steve Carlton for the Cardinals and who opened the talent pipeline for the club in Latin America.

Riddle was the scout who signed pitcher Steve Carlton for the Cardinals and who opened the talent pipeline for the club in Latin America.

Riddle was a Cardinals minor-league manager from 1955-62 before he became a scout, with responsibilities primarily for the Caribbean region and southeastern United States.

In 1963, John Buik, an American Legion coach in North Miami, Fla., contacted Riddle, tipping him off to a gangly left-handed pitcher on the team named Steve Carlton.

“Chase Riddle was a nice guy,” Buik said in a 1996 interview with Baseball Digest magazine. “He was a good scout and a good worker.”

Riddle liked what he saw of Carlton. Other teams, especially the Pirates, also had been scouting Carlton, so Riddle felt a sense of urgency to act.

“Chase convinced me there would be a good opportunity for advancement with the Cardinals,” Carlton told The Sporting News in June 1972.

Riddle arranged for Carlton to participate in a tryout for Cardinals personnel in St. Louis in September 1963.

“I threw as hard as I could and as well as I could, but I don’t think I threw fast enough for them,” Carlton recalled in a May 1967 interview with The Sporting News. “They were looking mostly for that hummer.”

Besides Riddle, the only other observer that day impressed by Carlton was Cardinals pitching coach Howie Pollet. “I liked Steve’s sneaky fastball and I felt his curve was good enough to make him worth a $5,000 gamble,” Pollet said. “I figured he could improve a lot more with experience than the other kids.”

With Pollet’s significant support, Riddle signed Carlton for $5,000.

By April 1965, Carlton, 20, made his big-league debut with the Cardinals. He helped them to two National League pennants and a World Series title before he got into a contract dispute and was traded to the Phillies before the 1972 season.

Carlton is a member of the National Baseball Hall of Fame, with 329 wins and 4,136 strikeouts in a 24-year big-league career.

Meanwhile, Riddle used his connections in the Caribbean to sign players such as outfielder Jose Cruz for the Cardinals.

In separate articles in February 1970, The Sporting News noted, “George Silvey, (Cardinals) director of player procurement, had just returned from the Caribbean area, which he toured with Chase Riddle, the scout who has had a big hand in the Redbirds’ emphasis on signing Latin Americans in recent years.

“No fewer than 24 Latin Americans grace the rolls of the Cardinals’ organization. Scouts like Chase Riddle, Tony Martinez and (Carlos) Negron have been chiefly responsible for the recent emphasis on signing Latins.”

In 1978, Riddle left the Cardinals to become manager of the Troy University baseball team in Alabama. His Troy teams won NCAA Division II national titles in 1986 and 1987. Riddle remained Troy’s manager until 1990, compiling more than 430 wins.

Bergesch, a St. Louis native, joined the Cardinals organization in 1947 as a minor-league administrator. He was general manager or business manager of Cardinals farm clubs in Albany, Ga., Winston-Salem, N.C., Columbus, Ga., and Omaha, Neb.

Bergesch, a St. Louis native, joined the Cardinals organization in 1947 as a minor-league administrator. He was general manager or business manager of Cardinals farm clubs in Albany, Ga., Winston-Salem, N.C., Columbus, Ga., and Omaha, Neb. Managed by Joe Schultz, the 1962 Crackers had a lineup that included Cardinals prospects such as catcher Tim McCarver, outfielder Mike Shannon, second baseman Phil Gagliano, shortstop Jerry Buchek and pitcher Ray Sadecki.

Managed by Joe Schultz, the 1962 Crackers had a lineup that included Cardinals prospects such as catcher Tim McCarver, outfielder Mike Shannon, second baseman Phil Gagliano, shortstop Jerry Buchek and pitcher Ray Sadecki. When the Cardinals traded starting center fielder Bill Virdon to the Pirates in May 1956, they expected one of the players they acquired in the deal, Bobby Del Greco, to be a mainstay at the position.

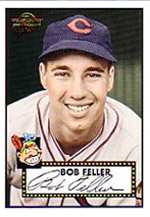

When the Cardinals traded starting center fielder Bill Virdon to the Pirates in May 1956, they expected one of the players they acquired in the deal, Bobby Del Greco, to be a mainstay at the position. The Indians, who signed Feller because of his fastball, wanted to test him against big-league batters and the exhibition provided an ideal opportunity.

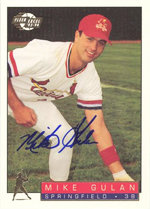

The Indians, who signed Feller because of his fastball, wanted to test him against big-league batters and the exhibition provided an ideal opportunity. In 122 games combined for Class AA Arkansas and Class AAA Louisville, Gulan had 17 home runs, 26 doubles and 77 RBI in 1995.

In 122 games combined for Class AA Arkansas and Class AAA Louisville, Gulan had 17 home runs, 26 doubles and 77 RBI in 1995.