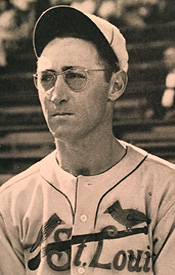

One look at Jimmie Reese was all it took for the Cardinals to entrust him with a position held by a future Hall of Famer.

On June 4, 1932, the Cardinals purchased Reese’s contract from the minor-league St. Paul Saints.

On June 4, 1932, the Cardinals purchased Reese’s contract from the minor-league St. Paul Saints.

On his first day with the Cardinals, Reese fielded so well at second base that manager Gabby Street kept him there the rest of the season and shifted Frankie Frisch to third.

A scrapper who energized the lineup, Reese had a short stint with the Cardinals, but a long career in baseball.

Hymie to Jimmie

Hyman Solomon was born in New York City in October 1901, a “son of an Irish mother and a Jewish father,” according to Red Smith of the St. Louis Star-Times.

The father suffered from tuberculosis and the family moved to Los Angeles when Hymie was 5. Hymie’s dad died a year later, according to the Star-Times.

The mother remarried and Hymie changed his name. Hymie was anglicized into Jimmie, and Solomon was dropped in favor of the last name of his mother’s second husband, Reese, the Orange County Register reported.

Jimmie Reese had a passion for baseball. In 1917, when he was 15, he became a bat boy for the minor-league Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League. From then until 1994, when he died at 92, Reese was employed in professional baseball over nine decades.

A left-handed batter, Reese was a second baseman with the Oakland Oaks of the Pacific Coast League before his contract was purchased by the Yankees.

Babysitter for Babe

In 1930, Yankees manager Bob Shawkey assigned Reese to be the road roommate of Babe Ruth because he hoped the clean-cut rookie might be a good influence on the notorious playboy. Ruth liked Reese and treated him well, but didn’t change his lifestyle. As Reese fondly said, “I roomed with his suitcase.”

Reese excelled as a pinch-hitter and backup at second to future Hall of Famer Tony Lazzeri. Reese hit .346 overall in 1930 and had a .519 on-base percentage as a pinch-hitter (12 hits, two walks, 27 plate appearances).

Just as impressively, Reese earned the respect of his star-studded teammates for his professionalism and demeanor. “A prince among good fellows,” Lou Gehrig wrote on a photo he autographed for Reese.

After wrenching a knee in spring training and hitting .241 in 1931, Reese was traded by the Yankees to St. Paul.

Dazzling debut

Being sent back to the minors “knocked me out,” Reese told the Star-Times. “I was broken-hearted and I couldn’t get the old spirit back. I was a complete flop in St. Paul.”

When told during a road trip to Milwaukee that his contract had been purchased by the Cardinals, “I never was so happy in my life,” Reese said.

Reese departed Milwaukee by train the night of June 4, 1932, and arrived in St. Louis the next day, just in time for the Cardinals’ doubleheader against the Reds.

With Frisch out because of leg ailments, Reese started at second base in both games, singled in his first at-bat as a Cardinal, and dazzled on defense.

With a runner on first, the Reds’ Mickey Heath “hit a sharp grounder toward second base. It looked like a sure hit, but Reese raced over for a pretty stop, stepped on the bag and then, still in full stride, cocked an eye toward first and flipped the ball to Rip Collins for a double play,” the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported. Boxscore

For the doubleheader, Reese handled 18 chances without an error, turned five double plays, totaled two hits and a walk, and scored a run. Boxscore

Displaying desire

When Frisch returned to the lineup June 8, he moved to third base and Reese stayed at second. Three days later, Reese collided with Dodgers catcher Al Lopez and tore shoulder ligaments. After sitting out 10 days, Reese “came back, his shoulder lumpy with bandages, and played courageously despite the pain,” the Star-Times reported.

Reese played “with a grin as broad as a south side cop’s shirtfront, a pair of legs that are brothers to the west wind, and a heart simply groaning under its load of ambition,” Red Smith wrote.

His style fit well with the Cardinals, who were the reigning World Series champions and developing their Gashouse Gang persona.

Regarding Frisch, Reese told the Los Angeles Times, “What a money player. He wasn’t as good when there was nothing at stake.”

Reese also saw similarities between Babe Ruth and Cardinals pitcher Dizzy Dean. “Dean thought he could get any human being out, and Ruth thought he could hit any human being,” Reese said. “Dean and Pepper Martin, they were pranksters, but they never hurt anybody. They were kids at heart.”

Reese’s contributions to the 1932 Cardinals included:

_ A two-run walkoff double to beat the Cubs. Boxscore

_ Four RBI in a game against the Giants. Boxscore

_ Four hits in a game versus the Dodgers. Boxscore

“He uses his head at the plate, waits out the pitcher, chokes his bat and slices line singles over the heads of the infielders,” the Star-Times noted.

Described by Smith as “a scintillating defensive player,” Reese made 71 starts at second base for the 1932 Cardinals and had a mere nine errors in 645 innings. He hit .265.

Gentleman of the game

After the season, the Cardinals couldn’t resist signing Rogers Hornsby, who was released by the Cubs. Hornsby, the former Cardinal and future Hall of Famer, was projected to be a pinch-hitter and backup to Frisch at second base.

Seeing he wasn’t in the Cardinals’ plans, Reese asked for permission to make a deal for himself with another club, the St. Louis Globe-Democrat reported. The Cardinals agreed. In February 1933, Reese’s contract was purchased by his hometown Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League.

Reese never again played in the majors, but he stayed in baseball the rest of his life. After his playing career, he primarily was a scout and minor-league coach. He tried managing in the minors but didn’t like it. “Ballplayers can be like children,” he told the Los Angeles Times, “and I just couldn’t get tough. When I was managing, all I did was worry.”

Reese was 70 when he became a big-league coach for the first time with the 1972 Angels. He continued to serve in uniform for the Angels until his death 22 years later. Los Angeles Times columnist Mike Penner pegged Reese “the spirit-lifter” for the club.

“He elevated the status of those around him simply by his presence,” Penner wrote. “He generated more goodwill and publicity for this team in a single day than a thousand spin-doctoring press conferences.”

Reese was a mentor and friend to several players, including Nolan Ryan, who named his second son Reese in honor of the coach. “There are special people in your life who make an impact on you,” Ryan told the Los Angeles Times. “Jimmie was that to me. He helped me on and off the field.”

Reese amazed players with his ability to place a ball almost anywhere he wanted with a fungo bat. He created the bats from hickory or oak, one side rounded, the other flat, in a workshop behind his house. He also had a hobby of making wood picture frames and giving them to friends, the Orange County Register noted.

At the memorial service for Reese in July 1994, uniforms from the Yankees, Cardinals and Angels were displayed. The Angels retired his uniform No. 50.

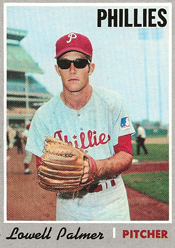

Palmer wore shades when he pitched, not to look cool, but because his eyes were highly sensitive to light. To a batter peering from the plate to the mound, the sight of a hard thrower with erratic control in a pair of black sunglasses could be unsettling, if not intimidating.

Palmer wore shades when he pitched, not to look cool, but because his eyes were highly sensitive to light. To a batter peering from the plate to the mound, the sight of a hard thrower with erratic control in a pair of black sunglasses could be unsettling, if not intimidating. “He has sensitive eyes, so he wears dark glasses that look as though they were carved out of chunks of bituminous coal when he pitches,” Stan Hochman wrote in the Philadelphia Daily News.

“He has sensitive eyes, so he wears dark glasses that look as though they were carved out of chunks of bituminous coal when he pitches,” Stan Hochman wrote in the Philadelphia Daily News. A left-hander, Cumberland made his debut in the majors with the Yankees. He later joined Juan Marichal and Gaylord Perry as a starter for the division champion Giants, and got his last win in the big leagues as a reliever with the Cardinals.

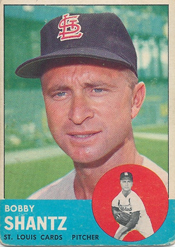

A left-hander, Cumberland made his debut in the majors with the Yankees. He later joined Juan Marichal and Gaylord Perry as a starter for the division champion Giants, and got his last win in the big leagues as a reliever with the Cardinals. On May 7, 1962, the Cardinals traded pitcher John Anderson and outfielder Carl Warwick to the Houston Colt .45s for Shantz.

On May 7, 1962, the Cardinals traded pitcher John Anderson and outfielder Carl Warwick to the Houston Colt .45s for Shantz. On April 15, 1972, in a swap of pitchers, the Cardinals sent Jerry Reuss to the Astros for Spinks and Lance Clemons.

On April 15, 1972, in a swap of pitchers, the Cardinals sent Jerry Reuss to the Astros for Spinks and Lance Clemons. On April 11, 1932, six months after they became World Series champions, the Cardinals dealt left fielder Chick Hafey to the Reds for pitcher Benny Frey, first baseman Harvey Hendrick and cash.

On April 11, 1932, six months after they became World Series champions, the Cardinals dealt left fielder Chick Hafey to the Reds for pitcher Benny Frey, first baseman Harvey Hendrick and cash.