Looking to strengthen a starting rotation that already included 30-game winner Dizzy Dean, Branch Rickey, the Cardinals’ teetotaling general manager, acquired the Cubs’ Pat Malone, who drank highballs as fervently as he threw high fastballs.

Three weeks after the Cardinals beat the Tigers in World Series Game 7, Rickey traded catcher Ken O’Dea for Malone and cash on Oct. 26, 1934.

A husky right-hander, Malone, 32, was a two-time 20-game winner who twice helped the Cubs earn National League pennants (1929 and 1932), dethroning the Cardinals each time.

A fierce competitor, Malone had a reputation as a baseball bad boy off the field. “Pat was a problem child,” the Minneapolis Star noted. “He loved his firewater.” According to Sec Taylor of the Des Moines Register, “He just couldn’t leave the bottle alone.”

As the St. Louis Post-Dispatch put it, Malone could be found “where the lights are bright and the glasses tinkling.”

On the urging of manager Frankie Frisch, Rickey took a chance on the hurler.

Malone “ought to win 15 games for us,” Frisch said to the Post-Dispatch.

Rickey predicted to the St. Louis Star-Times, “I believe he’ll win 20 games for us.”

As it turned out, Malone never pitched in a regular-season game for the Cardinals.

Rough and tumble

Born in Altoona, Pa., Perce Leigh Malone was named in honor of a family friend, Perce Lay, a brakeman on the Pennsylvania Railroad, but he preferred to be called Pat. As The Sporting News noted, “Nobody called him Perce from the day he was able to put his hands up, and Pat was handy with his dukes.”

Malone went to work for the railroad as a fireman when he was 16. A year later, he joined the Army as a cavalry soldier. After his military service, Malone went back to railroading and also played sandlot baseball. His first year as a professional pitcher was 1921 with Knoxville.

He spent seven seasons in the minors. When he got to the Cubs in 1928, Malone lost his first five decisions. Manager Joe McCarthy stuck with him and the grateful rookie finished the season with 18 wins. “He thought McCarthy was the greatest guy in the world and McCarthy, who liked his spirit, thought right well of him, too,” New York Sun columnist Frank Graham observed.

According to the Minneapolis Star, “McCarthy never questioned (Malone’s) conduct off the field so long as he produced on it.”

Catching Malone’s blazing fastball took a toll on Gabby Hartnett, whose hand “often was puffed to three times its normal size,” The Sporting News noted.

The Cubs became National League champions in 1929 and Malone was a major factor. He led the league in wins (22), shutouts (five) and strikeouts (166). His record that season against the defending champion Cardinals was 5-0.

Malone won 20 again in 1930, but McCarthy was fired near the end of the season and replaced by Rogers Hornsby.

In the book “The Man in the Dugout,” Cubs second baseman Billy Herman told author Donald Honig, “Hornsby tried to have discipline on the club, but he had some bad actors and couldn’t control them _ fellows like Pat Malone and (outfielder) Hack Wilson. They’d get drunk and get into fights.”

As Si Burick of the Dayton Daily News noted, Malone “was mixed up in several unpleasantries as a direct result of his convivial escapades.” In one of those incidents, Malone assaulted two Cincinnati sports reporters.

Behavior clause

Charlie Grimm took over for Hornsby during the 1932 season and guided the Cubs to a pennant, but he and Malone had a falling out in 1934. Malone won eight of his last 10 decisions, raising his 1934 season record to 14-7, but Grimm yanked him from the starting rotation after Aug. 24. Malone said the Cubs had promised to give him a $500 bonus for each win above 15 and that’s why Grimm stopped starting him, the Star-Times reported.

Malone wanted out. During the 1934 World Series, he met with Frankie Frisch, who asked Rickey to arrange a trade, the Star-Times reported.

As the Post-Dispatch noted, “Malone is not exactly the kind of player Branch Rickey would choose.” To close the deal, the Cubs gave the Cardinals “considerable cash,” according to the Star-Times.

Rickey “practically clinched the 1935 National League championship for the Cardinals” when he got Malone to join a starting rotation with Dizzy Dean, Paul Dean, Bill Walker and Bill Hallahan, the Star-Times proclaimed.

The good vibes evaporated, though, when Rickey mailed a contract to Malone offering a 1935 salary of $5,000, a 50 percent cut from his pay with the Cubs in 1934. Malone sent back the document, unsigned, with a note: “Haven’t you made a mistake and sent me the batboy’s contract?”

According to the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, Rickey said the low offer was his way of emphasizing to Malone that the Cardinals didn’t consider him of much value unless he agreed to curb his drinking. Rickey said he didn’t plan to keep Malone unless he expressed “a strong determination to be a very, very well-behaved boy,” the Post-Dispatch reported.

Malone came to St. Louis, met with Rickey for more than two hours, promised he’d behave, and emerged with a signed contract. According to the Post-Dispatch, the contract had “a provision for a bonus if he refrained from tasting liquor during the training and league seasons, and for heavy fines if he wandered from the straight and non-intoxication path.”

Both appeared satisfied. Rickey said to the Post-Dispatch, “I expected to find horns on this man, Malone, but he hasn’t any.”

Malone told the newspaper, “Rickey isn’t the big, bad wolf I expected to meet.”

Math problem

A portly Malone lumbered into Cardinals spring training headquarters at Bradenton, Fla., in 1935. “There isn’t a uniform in camp big enough to give Malone arm freedom,” the Star-Times noted.

Following a morning of workouts early in camp, Malone accepted an invitation from Dizzy Dean to play golf that afternoon. After six holes, Malone “broke down. He sent his caddy back to the clubhouse with his sticks, called for a taxicab and went to the club’s hotel,” the Post-Dispatch reported. “Straight to his room he went, without bothering about food, and he was snoring before 6 o’clock.”

The next morning he told the newspaper, “I can barely move one leg after another. I never knew what work was until I came to this Cardinals camp.”

Determined to show the Cardinals he could contribute, Malone became “one of the hardest workers on the field,” the Post-Dispatch reported. “He showed the zest of a rookie.”

According to the Globe-Democrat, “Pat has given every indication of his willingness, nay, his eagerness, to cooperate to the fullest to become a regular and reliable starting pitcher when the season opens.”

Branch Rickey saw it differently. On March 26, 1935, he sold Malone’s contract to the Yankees, who were managed by Joe McCarthy, for a reported $15,000. According to the Post-Dispatch, Malone said to Rickey, “If you had kept me, I’d have shown you something. I’d have worked my head off and won for you.”

Describing the trade as a “surprise,” the Post-Dispatch added that Malone’s conduct “on and off the field during the training season has been all that anyone could have asked.”

While offering no specific reasons for the deal, Rickey said to the Star-Times, “I feel relieved considerably now that Malone is off our ballclub … After surveying conditions here for a week, I realized Malone was not the type I desired on a world championship team or a team that is going to try to win another pennant.”

Rickey told the Post-Dispatch, “There are four phases of arithmetic: addition, multiplication, division and subtraction. Applied to baseball, subtraction is the most important … I have subtracted Malone from the Cardinals’ roster. He cannot lose any games. He cannot lead any of our little boys astray. Ergo, the Cardinals are stronger.”

End of the line

Used primarily by McCarthy as a reliever, Malone was 19-13 with 18 saves in three seasons with the Yankees, helping them to two American League pennants (1936 and 1937).

Released in 1938, Malone joined the minor-league Minneapolis Millers at spring training in Daytona Beach, Fla., and was fitted for a uniform. “He stood there, a Coca-Cola in one hand and a cigarette in the other, while two men plied his Ruthian form with tape measures,” the Minneapolis Star reported.

Trouble soon followed. Manager Donie Bush told the newspaper, “Malone began drinking while the team was at Daytona Beach and we had several arguments about it then.”

Bristling against discipline by a minor-league club, Malone rebelled and twice was suspended within a week early in the season for getting drunk. He pitched for two more minor-league teams in 1938, his final year in professional baseball, before returning home to Altoona.

In October 1939, the Yankees were headed to Cincinnati for the World Series when the train stopped in Altoona for about 10 minutes. Malone climbed onboard, spent time with Joe McCarthy and went through the cars, saying hello to the players, according to columnist Frank Graham.

When it came time for the train to depart, Malone said to McCarthy, “Well, Joe, I wish to hell I was going with you.” McCarthy replied, “I wish you were, too, Pat.”

According to Harold C. Burr of the Brooklyn Eagle, Malone “stood on the station platform and watched the lighted windows of the Pullmans go streaking past. It was Malone’s wistful farewell to baseball.”

On Oct. 2, 1974, the Pirates’ Bob Robertson swung and missed at strike three, a strikeout that should have ended the game. A Cubs win would have kept alive the Cardinals’ division title hopes.

On Oct. 2, 1974, the Pirates’ Bob Robertson swung and missed at strike three, a strikeout that should have ended the game. A Cubs win would have kept alive the Cardinals’ division title hopes. On Sept. 5, 1974, the Cardinals acquired Hunt, a second baseman, after the Expos placed him on waivers. Born and raised in St. Louis, Hunt got to close out his playing career in his hometown with the 1974 Cardinals.

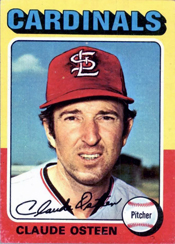

On Sept. 5, 1974, the Cardinals acquired Hunt, a second baseman, after the Expos placed him on waivers. Born and raised in St. Louis, Hunt got to close out his playing career in his hometown with the 1974 Cardinals. That doesn’t count the unofficial shutout Osteen crafted for the Cardinals.

That doesn’t count the unofficial shutout Osteen crafted for the Cardinals. _ In his big-league debut with the Cardinals, he got a start against the Dodgers and was opposed by Sandy Koufax.

_ In his big-league debut with the Cardinals, he got a start against the Dodgers and was opposed by Sandy Koufax. On July 31, 2014, the Cardinals acquired Lackey from the Red Sox for outfielder Allen Craig and pitcher Joe Kelly. The Red Sox also sent the Cardinals a minor-league pitcher, Corey Littrell, and $1.75 million cash.

On July 31, 2014, the Cardinals acquired Lackey from the Red Sox for outfielder Allen Craig and pitcher Joe Kelly. The Red Sox also sent the Cardinals a minor-league pitcher, Corey Littrell, and $1.75 million cash.