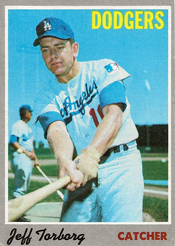

A catcher who earned the trust of Sandy Koufax, Don Drysdale and Nolan Ryan, Jeff Torborg came to the Cardinals to work with a pitching staff led by Bob Gibson.

On Dec. 6, 1973, the Cardinals acquired Torborg from the Angels for pitcher John Andrews. With 10 years of big-league experience and a reputation as a defensive specialist who worked well with pitchers, Torborg, 32, seemed a good fit to back up Cardinals catcher Ted Simmons, 24, in 1974.

Instead, when the Cardinals decided on a different roster configuration, Torborg departed and began a second career as a coach and manager.

Giants fan

As a youth in Westfield, N.J., Torborg was a New York Giants fan. “I remember walking on the field (after attending a game) at the Polo Grounds with my dad and I couldn’t believe I was really there,” Torborg recalled to the Bridgewater (N.J.) Courier-News. “I remember seeing Monte Irvin hit one into the upper deck in the deepest part of left field, and I couldn’t imagine anybody hitting the ball that far.”

Torborg played college baseball at Rutgers and was a power-hitting catcher. After he saw Torborg hit two home runs and a triple in a game against Army, Dodgers scout and former Giants infielder Rudy Rufer said to the Courier-News, “I raced for the nearest phone, called up (general manager) Buzzie Bavasi, and told him Torborg was a prospect we couldn’t afford to miss.”

A right-handed batter, Torborg hit .537 for Rutgers in 1963 and produced 67 total bases in 67 at-bats.

The Dodgers signed him on May 23, 1963, and sent him to their Albuquerque farm club. He arranged to return home to receive his Rutgers diploma on June 5 (he earned a degree in education), got married the next day to a former Miss New Jersey, Susan Barber, and went back to Albuquerque on June 8.

(The Dodgers gave Torborg and his wife a two-week paid honeymoon in Hawaii after the season, according to the Courier-News.)

Higher education

Torborg, 22, made the Opening Day roster of the 1964 Dodgers as a backup to catcher John Roseboro. Don Drysdale dubbed the rookie “Rudy Rutgers” because he looked the part of a clean-cut collegian, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported.

Sandy Koufax, a bachelor, had a collection of kitchen appliances he’d received for being a guest on postgame radio shows. One day, in the locker room, he handed Torborg a new electric can opener. According to author Jane Leavy in the book “A Lefty’s Legacy,” Koufax said to the newly married Torborg, “You can use this more than me.”

On days Koufax didn’t pitch, he would hit fungoes to Torborg so that the rookie could acclimate himself to pop-ups behind the plate at Dodger Stadium, Leavy noted. She also explained in her book that Koufax told Torborg to stop jumping up from his crouch after every pitch. “I like the picture of the catcher being quiet behind the plate, staying down, so everything I see is low,” Koufax said.

John Roseboro also would “offer help every chance he had,” Torborg said to the Los Angeles Times. According to The Sporting News, Torborg was grateful to Roseboro for “tutoring him on how to handle low pitches and block the plate.”

Torborg didn’t hit well in the majors but he had his moments. On July 25, 1965, he contributed a two-run single against the Cardinals’ Nelson Briles in a five-run Dodgers fifth inning. Boxscore Five days later, he sparked a Dodgers comeback at St. Louis with a home run against Curt Simmons that went deep over the hot dog stand in left. Boxscore

The highlight of Torborg’s 1965 season came on Sept. 9 at Dodger Stadium when he caught Koufax’s perfect game against the Cubs.

As Koufax crafted his masterpiece, “my heart was beating so loudly it was pounding in my ear,” Torborg said to the Los Angeles Times. Boxscore

All rise

Torborg was Roseboro’s backup for four seasons (1964-67). When Roseboro got traded to the Twins, “I felt I was No. 1,” Torborg told the Los Angeles Times. Instead, the Dodgers acquired Tom Haller from the Giants and made him the starting catcher.

“I got very frustrated,” Torborg said to the Times. “I let myself get overweight and I had back trouble.”

Torborg was the catcher when Don Drysdale beat the Giants on May 31, 1968, for his fifth consecutive shutout, and he caught Bill Singer’s no-hitter against the Phillies on July 20, 1970. Boxscore and Boxscore

Mostly, though, Torborg watched as Haller did the bulk of the Dodgers’ catching from 1968-70. Torborg served so much time on the bench he was nicknamed “The Judge,” according to The Sporting News.

Change of scenery

In March 1971, Torborg was sent to the Angels. He shared catching duties with John Stephenson and Jerry Moses in 1971 and with Art Kusnyer and Stephenson in 1972.

With Bobby Winkles as manager and John Roseboro as a coach for the Angels in 1973, Torborg, 31, finally became a No. 1 catcher.

On May 15, 1973, Torborg caught his third career no-hitter, the first of seven pitched by Nolan Ryan. “He called an outstanding game,” Ryan told The Sporting News. Boxscore

(Since then, Carlos Ruiz of the Phillies and Jason Varitek of the Red Sox each caught four no-hitters, according to MLB.com.)

With the 1973 Angels, Torborg played in a career-high 102 games, but hit .220. As he told Bob Broeg of the Post-Dispatch, “I’m a no-hit catcher in more ways than one.”

After the season, the Angels acquired catcher Ellie Rodriguez from the Brewers and projected him to be the starter in 1974.

New script

Ted Simmons caught in 152 games, totaling a franchise-record 1,352.2 innings, for the 1973 Cardinals. Hoping to give him more breaks from the grind in 1974, the Cardinals acquired Torborg.

(According to The Sporting News, Nolan Ryan “loved to pitch to” Torborg and “was upset” when he got traded.)

The Cardinals went to 1974 spring training with four catchers on the roster _ Simmons, Torborg, Larry Haney and Marc Hill. According to the 1974 Cardinals media guide, Torborg “has a good chance to be the No. 2” catcher.

Described by The Sporting News as “a proficient receiver with an excellent arm,” Torborg told the publication, “I feel I can help (the Cardinals) a lot even if I’m not playing. I can help the pitchers in the bullpen and I can talk with the pitching coach (Barney Schultz) on the bench.”

Late in spring training, the Cardinals decided that their catcher from the 1960s, Tim McCarver, 32, who was on the roster as a reserve first baseman, would suffice as the backup to Simmons. In an emergency, first baseman and former catcher Joe Torre also could fill in.

Torborg was released, Larry Haney got sent to the Athletics and Marc Hill went to the minors.

“I had a pretty good spring, but the Cardinals ran into a (roster) numbers problem and they let me go,” Torborg told The Sporting News.

Torborg went home to New Jersey. Two months later, in May 1974, the Red Sox brought him to Boston for a tryout after catcher Carlton Fisk injured a knee, but they opted to go with Tim Blackwell as the backup to Bob Montgomery.

At 32, Torborg’s playing days were finished. Among the Hall of Famers he caught were Don Sutton (51 games), Drysdale (49 games), Ryan (41 games) and Koufax (24 games).

Coach and manager

Torborg, who earned a master’s degree in athletic administration from Montclair (N.J.) State, became athletic director and head baseball coach at Wardlaw School in Edison, N.J., but left for a spot on the 1975 Cleveland Indians coaching staff of manager Frank Robinson.

In June 1977, Torborg, 35, replaced Robinson as manager. Years later, he told the Bridgewater Courier-News, “I really wasn’t prepared to manage. I was a young coach who was still very close to the players. I made a lot of mistakes.”

After he was fired in July 1979, Torborg joined the Yankees coaching staff in 1980. He was ready to become head baseball coach at Princeton in 1982 but changed his mind when Yankees owner George Steinbrenner gave him a seven-year contract to stay as a coach.

According to Newsday’s Tom Verducci, Steinbrenner offered Torborg the Yankees general manager job in 1982 but he rejected it because he wanted to remain in a role on the field. Billy Martin, one of several managers Torborg coached for with the Yankees, distrusted him. “He thought I was a pipeline upstairs (to Steinbrenner),” Torborg told Verducci.

After nine seasons (1980-88) as a Yankees coach, Torborg managed the White Sox (1989-91), Mets (1992-93), Expos (2001) and Marlins (2002-2003).

In 1992, Torborg and Mets outfielder Vince Coleman “engaged in an angry and physical confrontation on the field,” the New York Times reported. Coleman was suspended for two days without pay for shoving Torborg and swearing at him after the Mets manager tried to break up Coleman’s argument with an umpire.

According to New York Times columnist George Vecsey, “Coleman has been both a cause and a symbol of the Mets’ slide to the bottom. This is an outfielder with little baseball savvy and bad wheels and an unsavory image.”

Doing the unexpected came naturally to MacKenzie. A hockey player from a small town on a Canadian island, he went to Yale, graduated and became a big-league pitcher.

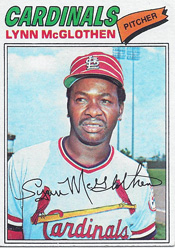

Doing the unexpected came naturally to MacKenzie. A hockey player from a small town on a Canadian island, he went to Yale, graduated and became a big-league pitcher. On Dec. 7, 1973, the Cardinals acquired John Curtis, Mike Garman and Lynn McGlothen from the Red Sox for Reggie Cleveland, Diego Segui and Terry Hughes. It was the second major trade between the teams since the end of the season. Two months earlier,

On Dec. 7, 1973, the Cardinals acquired John Curtis, Mike Garman and Lynn McGlothen from the Red Sox for Reggie Cleveland, Diego Segui and Terry Hughes. It was the second major trade between the teams since the end of the season. Two months earlier,  In April, he served with the National Guard, trying to quell riots in Washington, D.C. In the fall, he went to Vietnam, looking to boost the spirits of U.S. troops. In between, he pitched in relief for the Baltimore Orioles.

In April, he served with the National Guard, trying to quell riots in Washington, D.C. In the fall, he went to Vietnam, looking to boost the spirits of U.S. troops. In between, he pitched in relief for the Baltimore Orioles.