Depending on how often his fastball found the strike zone, Bobo Newsom could be entertainingly good or entertainingly bad _ sometimes both in the same day.

The few fans who came to St. Louis’ Sportsman’s Park in September 1934 witnessed classic Bobo.

A big right-hander (6-foot-3, 220 to 240 pounds, according to the Associated Press), Bobo started Game 1 of a doubleheader for the Browns against the Athletics on Sept. 14, walked the first four batters and was yanked. To nearly everyone’s surprise, he started Game 2 as well and, this time, struck out the first four batters. He went on to pitch a complete game and earn the win.

Four days later, Bobo started at home against the Red Sox. He pitched a no-hitter for nine innings _ and lost, in the 10th.

Give me a break

Louis Newsom of Hartsville, S.C., began pitching in the minors when he was 20 in 1928. His nickname was Buck, but he became “known to all as Bobo because that was the way he greeted everybody, from the owner of the club to the team’s batboy,” according to the Associated Press.

After a stint with the Dodgers (1929-30), Bobo was claimed by the Cubs. On his way to Chicago to talk contract, his car spun down an embankment and Bobo suffered a compound fracture of the left leg, the Detroit Free Press reported.

Two days after he was able to begin moving around again, Bobo accompanied an uncle to a mule sale in South Carolina. Bobo got kicked in the bum leg by a mule and suffered two broken bones, he told the Free Press.

Limited to one appearance with the 1932 Cubs, Bobo went back to the minors with the 1933 Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League and won 30 games. The Browns claimed him on the recommendation of their manager, Rogers Hornsby, who managed the Cubs when Bobo was there. “I think Newsom has real stuff,” Hornsby said to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

St. Louis showboat

Using a corkscrew windup, Bobo would “spin off the mound and fire a sidearm fastball,” the Free Press noted.

Post-Dispatch columnist John Wray wrote, “Newsom throws about the fastest ball in the league, if not the majors.”

Senators manager Bucky Harris told the Washington Star, “He had the damndest arm I ever saw.”

Bobo talked a good game, too. The Buffalo News described him as “made up of almost equal parts of bombast, braggadocio and brilliance.”

Morris Siegel of the Star observed, “He was frivolous, cantankerous, often careless with the truth, competitive and garrulous, but fun most of the time.”

Arthur Daley wrote in the New York Times that Bobo “was the only pitcher who could swagger while standing still.”

When Bobo popped off at Detroit reporter Robert Ruark, the journalist tried to pop him with a punch. Later, Ruark recalled Bobo as “one of the finest non-malicious liars I ever knew … He was a braggart and a blowhard, but I never knew anybody who really disliked him.”

Wild thing

Hornsby pitched Bobo in 47 games with the 1934 Browns. He won 16, lost 20 _ a record that might have been reversed with better control. Bobo totaled more walks (149) than strikeouts (135).

When Bobo got pulled after walking the first four batters of the Sept. 14 doubleheader opener, he figured to be done for the day, but George Blaeholder, who was supposed to start Game 2, got sick. The 500 spectators on hand in St. Louis that Friday afternoon “were somewhat surprised to see” Bobo warming up as Blaeholder’s replacement, the Post-Dispatch reported.

More surprising, too, was how Bobo reversed his performance from the opener, striking out the first four batters. He fanned just one more after that, but held the Athletics to two runs in nine innings for the win. Boxscore and Boxscore

In his next start, the nine hitless innings against the Red Sox, Bobo’s control cost him a win. He walked seven, and two of those scored.

Played on a Tuesday afternoon at Sportsman’s Park (no attendance was reported but each of the other three games of the Red Sox-Browns series drew 500 or less), Bobo gave up a run in the second. Red Sox cleanup hitter Roy Johnson led off the inning with a walk and, after an error and an out, scored from third on a fielder’s choice.

With the score tied at 1-1 in the 10th, Bobo walked Max Bishop and Billy Werber. With two outs, Johnson grounded a 3-2 pitch up the middle. Shortstop Alan Strange “made a gallant try for the ball but it just tipped the finger of his glove as it went to center,” scoring Bishop with the winning run, the Post-Dispatch reported. Boxscore

(Bobo pitched five more one-hitters in the majors and won all.)

Show must go on

In May 1935, the Browns sold Bobo’s contract to the Senators for $40,000. As he departed St. Louis, Bobo told the Buffalo News, “Brownie fans have been my friends _ both of them.”

Bobo had two more stints with the Browns _ 1938-39 and 1943. He won 20 for the 1938 Browns. In July 1943, after being suspended for insubordination by Dodgers manager Leo Durocher, prompting his teammates to threaten to strike unless he was reinstated, Bobo was banished to the Browns.

“I don’t want to play in St. Louis,” Bobo said to the Associated Press. “I will quit before reporting to St. Louis.”

Bobo reported, went 1-6, then was peddled to the Senators.

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt was in attendance when Bobo started on Opening Day for the Senators at home against the Yankees. In the fifth inning, Senators third baseman Ossie Bluege charged in to field a Ben Chapman bunt and heaved a strong throw toward first. Bobo, standing directly in the path of the ball, forgot to duck. With a sickening smack, the ball struck him full force just below the right ear. President Roosevelt “dropped his bag of peanuts and sat transfixed” as Bobo clutched his face in his hands, the Washington Star reported.

Disregarding the advice of a doctor, Bobo insisted on staying in the game. As the Washington Star put it, “This big galoot with an unmatchable heart refused to quit after punishment that would have hospitalized an ordinary mortal.”

Bobo pitched a complete game, limiting the Yankees to four singles, and won, 1-0. President Roosevelt stayed for the entire show. Boxscore

Bobo served five separate terms with Washington. “That’s one more than FDR’s record,” he said to the Free Press.

Traveling man

It was tough to get Bobo, who pitched 246 complete games in the majors, to leave the mound.

Cleveland Indians slugger Earl Averill, who altered the career of Dizzy Dean with an All-Star Game smash that broke the left toe of the Cardinals’ ace, drilled a liner that struck Bobo in the left knee during the third inning of a game at Washington.

“After briskly rubbing the knee, he declared he was ready to pitch,” the Star reported. With trainer Mike Martin applying ice packs between innings, Bobo pitched a complete game, but lost by a run. That night, X-rays showed he had a fractured kneecap. Boxscore

Bobo three times won 20 in a season and three times lost 20. He never led a major league in wins but four times led the American League in losses.

In 1940, he was 21-5 for the Tigers, who won the American League pennant. In the World Series against the Reds, Bobo’s father watched from the stands as his son started and won Game 1. The next morning, Bobo’s father died. After the funeral, Bobo started Game 5 and pitched a three-hit shutout. Two days later, in the decisive Game 7, Bobo limited the Reds to two runs, but the Tigers scored just one against Paul Derringer and lost. Boxscore, Boxscore, Boxscore

Bobo arrived at 1941 spring training “in a long auto with a horn that blared ‘Hold That Tiger,’ and a neon sign that flashed, ‘Bobo,’ ” The Sporting News reported.

He was 12-20 that season.

Described by The Sporting News as “a modern day Marco Polo,” Bobo pitched for nine big-league teams _ Dodgers, Cubs, Browns, Senators, Red Sox, Tigers, Athletics, Yankees, Giants _ and posted a record of 211-222. “He moved around like a hobo, changing uniforms almost with the seasons,” Joe Falls of the Free Press noted.

In his first big-league game, Bobo pitched to High Pockets Kelly, a future Hall of Famer who began in the majors in 1915. In his last big-league game, Bobo pitched to Larry Doby, a future Hall of Famer and first black to reach the American League. Boxscore and Boxscore

“The toughest man I ever faced in the clutch was Lou Gehrig,” Bobo told the Associated Press. “He always seemed to rise to the occasion.”

Gehrig’s numbers against Bobo: .337 batting average, .450 on-base percentage, six home runs.

Bobo also was hit hard by Joe DiMaggio (.380 batting average, .413 on-base mark, seven homers), Stan Musial (four hits, including two homers, in five at-bats for an .833 average) and Ted Williams (.385 batting average, .515 on-base mark.)

“DiMaggio, Musial and Ted Williams _ all three great hitters,” Bobo said to the Associated Press. “I wouldn’t try to choose between them.”

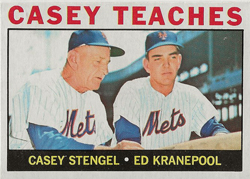

Ed Kranepool was the teen Stengel started that day, putting him in the No. 3 spot in the order ahead of cleanup hitter and future Hall of Famer Duke Snider.

Ed Kranepool was the teen Stengel started that day, putting him in the No. 3 spot in the order ahead of cleanup hitter and future Hall of Famer Duke Snider. On Oct. 2, 1974, the Pirates’ Bob Robertson swung and missed at strike three, a strikeout that should have ended the game. A Cubs win would have kept alive the Cardinals’ division title hopes.

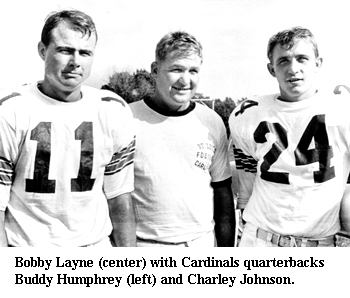

On Oct. 2, 1974, the Pirates’ Bob Robertson swung and missed at strike three, a strikeout that should have ended the game. A Cubs win would have kept alive the Cardinals’ division title hopes. In 1965, Layne joined the St. Louis Cardinals as quarterback coach, helping to refine Charley Johnson.

In 1965, Layne joined the St. Louis Cardinals as quarterback coach, helping to refine Charley Johnson. On Sept. 5, 1974, the Cardinals acquired Hunt, a second baseman, after the Expos placed him on waivers. Born and raised in St. Louis, Hunt got to close out his playing career in his hometown with the 1974 Cardinals.

On Sept. 5, 1974, the Cardinals acquired Hunt, a second baseman, after the Expos placed him on waivers. Born and raised in St. Louis, Hunt got to close out his playing career in his hometown with the 1974 Cardinals. Thomas had two seasons with the Dallas Cowboys and was their leading rusher in both. In his rookie season, they reached the Super Bowl for the first time. In his second season, they won it.

Thomas had two seasons with the Dallas Cowboys and was their leading rusher in both. In his rookie season, they reached the Super Bowl for the first time. In his second season, they won it.