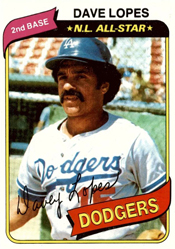

Imagine accomplishing a rare feat and doing it in the presence of the master of the craft. Davey Lopes knew the feeling.

On Aug. 24, 1974, Lopes had five stolen bases for the Dodgers against the Cardinals. Watching him perform was the National League’s all-time best base stealer, the Cardinals’ Lou Brock.

On Aug. 24, 1974, Lopes had five stolen bases for the Dodgers against the Cardinals. Watching him perform was the National League’s all-time best base stealer, the Cardinals’ Lou Brock.

Lopes became the first National League player to swipe five bases in a game since Dan McGann did it for the Giants against Brooklyn on May 27, 1904. Boxscore

Though he holds the record for most career stolen bases (938) in the National League, Brock never swiped five in a game. Neither did other prominent base stealers such as Ty Cobb, Tim Raines, Vince Coleman, Max Carey, Honus Wagner and Maury Wills.

Lopes remains the only player with five steals in a game versus the Cardinals.

Tough part of town

Lopes was born and raised in East Providence, Rhode Island, a town of Irish, Portuguese and Cape Verdean immigrants who came looking for jobs in the factories and along the waterfront.

One of 12 children, Lopes was a toddler when his father died, according to the Los Angeles Times. A stepfather abandoned the family. Lopes’ mother, Mary Rose, worked as a domestic when she could.

Residing in a tenement, Lopes described the neighborhood to Times columnist Jim Murray as “roaches, rats, poor living conditions, drugs as prevalent as candy.”

“If it hadn’t been for sports, there’s no telling what I’d be or where I’d be,” Lopes said to the Times in 1973. “All I had to do is step off the porch to a choice of all the things you associate with a ghetto … It’s an easy step off the porch.”

Before he learned to steal bases in ball games, Lopes said he resorted to shoplifting. “I never stole anything major, just clothes and baseballs and bats,” he told Jim Murray.

Lopes also said to the Times, “When you don’t have money and can’t have what the other kids have, you get it any way you can. You live on the street. You steal.”

Though, as Jim Murray put it, “even by Rhode Island standards, Davey was little,” he excelled in high school baseball and basketball. Among those who admired Lopes’ play was an opposing coach, Mike Sarkesian. A son of an Armenian immigrant who worked in steel foundries, Sarkesian grew up in a Providence tenement house, but went on to graduate from the University of Rhode Island with dual degrees in biology and physical education.

In the same year Lopes graduated from high school, Sarkesian was named head basketball coach and athletic director at Iowa Wesleyan College. He recruited Lopes, offering him a college education and providing an escape from East Providence. After two years at Iowa Wesleyan, Sarkesian became athletic director at Washburn University in Topeka, Kansas. Lopes went with him, arriving shortly after a tornado left the campus in shambles.

An outfielder, Lopes did so well in baseball that he got selected by the Giants in the eighth round of the 1967 amateur draft but opted to stay in college. The Dodgers drafted him in the second round in 1968 and Lopes signed for $10,000. He gave most of the money to his mother, according to the Times.

Though he played in the minors in the summers of 1968 and 1969, Lopes skipped spring training both years so that he could complete his studies at Washburn. He graduated in 1969 with a degree in elementary education and taught sixth grade one winter.

(Lopes also got married in July 1968 but continued to contribute to the education of brothers and sisters still in school. “I try and send home as much as I can, even when it hurts my own wallet,” he told the Times in 1973.)

On the run

Lopes wanted to be a center fielder, but Tommy Lasorda, who managed him for three seasons (1970-72) in the minors, suggested his best path to the big leagues was as an infielder. Lopes learned to play second base. He was 5-foot-9 and tough. “A Billy Martin with more talent and speed,” noted San Francisco Examiner columnist Art Spander.

Leigh Montville of the Boston Globe described Lopes as “a dirty uniform ballplayer” whose “game is motion, as much motion as he can create.”

After hitting .317 with 48 stolen bases for Lasorda with Albuquerque in 1972, Lopes, 27, was called up to the Dodgers that September. The next year, he replaced Lee Lacy as the Dodgers’ second baseman and took off running, igniting the offense from the leadoff spot.

“He sets our mood,” Dodgers manager Walter Alston said to the Los Angeles Times. “I will give him a red light in certain situations, but otherwise he can run whenever he wants.”

Lopes told the newspaper, “The steals are something to talk about, but when they turn into runs, that’s what is important.”

Right conditions

The Dodgers became National League champions in 1974. Lopes’ special blend of speed and power were highlighted that August. He had four stolen bases against the Astros on Aug. 4, becoming the first Dodger since Maury Wills in 1962 to swipe that many in a game. On Aug. 20, Lopes clouted three home runs and totaled five hits versus the Cubs at Wrigley Field. Boxscore and Boxscore

Four nights later, he had his five-steal game against the Cardinals’ battery of pitcher John Curtis and catcher Ted Simmons. The Dodgers totaled a club-record eight steals in the game and won, 3-0, with Don Sutton pitching the shutout.

Lopes, who reached base on three hits, a walk and an error, swiped second three times and third twice. He also was thrown out twice by Simmons _ at third with Curtis pitching and at second with Al Hrabosky on the mound.

“All five steals were my fault,” Curtis told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. “I was having trouble getting the ball over the plate.”

Curtis’ teammate, Lou Brock, said to the Los Angeles Times, “His delivery is systematic and easy (for a runner) to pick up.”

Brock also told the newspaper it was a myth that left-handers, such as Curtis, were more difficult to steal against. “Even though he’s looking right at you, you’re looking right at him, too,” Brock noted. “You can pick up so many keys to run from because they’re all there in front of you. Against a right-hander, all you see is his back and rear end. He can hide his motion better.”

Elite stealers

Brock also had a stolen base, his 88th of the season, in the game, and was headed for 118, breaking Wills’ record of 104.

In remarks to the Los Angeles Herald-Examiner, Lopes, 29, said of Brock, 35, “The first thing about him that amazes you is how he can steal all those bases at his age. The next thing is his ability to steal with the short lead he takes. Runners such as Joe Morgan, Cesar Cedeno, Bobby Bonds and myself take leads of at least seven to eight feet. Without that, we’d never get to second on time. Brock takes only five feet, mainly because of the speed he’s able to generate in a hurry.

“He picks up all those steals while only rarely attempting to take third. The other team knows he’s going to try for second. They get ready for him, but they seldom get him.”

Regarding Lopes’ five steals versus the Cardinals, Brock said to the Los Angeles Times, “So many conditions have to be exactly right. First, it has to be something a player wants very badly. He also has to defy a lot of things such as the unwritten rule that says you shouldn’t try to steal third with two outs … Also, it’s unusual for somebody to get that many opportunities _ that is, the number of pitches to the man batting behind him (Bill Russell).” Boxscore

The record for most steals in a game by one player is seven. George Gore did it for the Cubs in 1881 and Billy Hamilton matched the feat for the Phillies in 1894.

Those with six steals in a game: Eddie Collins for the Athletics twice in 1912, Otis Nixon of the 1991 Braves, Eric Young of the 1996 Rockies and Carl Crawford of the 2009 Rays.

Rickey Henderson, career leader in steals (1,406), had five in a game for the 1989 Athletics. The only Cardinals player with five steals in a game is Lonnie Smith, who did it Sept. 4, 1982, versus the Giants. Boxscore

Decades of service

Lopes finished the 1974 season with 59 steals. The next year, he swiped 38 in a row from June to August and led the league (with 77), ending Brock’s reign of four consecutive years. Lopes was the league leader again in 1976 (with 63 steals).

One of his best seasons was 1979 when he was successful on 44 of 48 steal attempts (his 91.67 percent success rate led the league) and slugged 28 home runs. His 28th homer was a walk-off grand slam against the Cubs’ Bruce Sutter. Boxscore

Lopes also was the league leader in stolen base percentage in 1985, swiping 47 in 51 tries (92.1 percent). For his career, he had a stolen base percentage of 83 percent, better than that of Henderson (80.7), Brock (75.3) and Wills (73.8).

In four World Series with the Dodgers, Lopes had 10 stolen bases in 12 tries.

His 16 years in the majors were with the Dodgers (1972-81), Athletics (1982-84), Cubs (1984-86) and Astros (1986-87), totaling 1,671 hits and 557 steals.

Lopes also managed the Brewers (2000-02) and coached for 27 years with the Rangers (1988-91), Orioles (1992-94), Padres (1995-99 and 2003-05), Nationals (2006 and 2016-17), Phillies (2007-10) and Dodgers (2011-15).

On Aug. 20, 1954, the Cardinals turned six double plays, tying a National League record, and still were beaten, 3-2, at home against the Reds.

On Aug. 20, 1954, the Cardinals turned six double plays, tying a National League record, and still were beaten, 3-2, at home against the Reds. In 11 seasons in the majors with the Braves (1962-67), Astros (1968-71) and Expos (1972), Lemaster was on the cusp of becoming an ace until injuries set him back. His record was 90-105, including 15-13 versus the Cardinals.

In 11 seasons in the majors with the Braves (1962-67), Astros (1968-71) and Expos (1972), Lemaster was on the cusp of becoming an ace until injuries set him back. His record was 90-105, including 15-13 versus the Cardinals. That doesn’t count the unofficial shutout Osteen crafted for the Cardinals.

That doesn’t count the unofficial shutout Osteen crafted for the Cardinals. _ In his big-league debut with the Cardinals, he got a start against the Dodgers and was opposed by Sandy Koufax.

_ In his big-league debut with the Cardinals, he got a start against the Dodgers and was opposed by Sandy Koufax. On July 31, 2014, the Cardinals acquired Lackey from the Red Sox for outfielder Allen Craig and pitcher Joe Kelly. The Red Sox also sent the Cardinals a minor-league pitcher, Corey Littrell, and $1.75 million cash.

On July 31, 2014, the Cardinals acquired Lackey from the Red Sox for outfielder Allen Craig and pitcher Joe Kelly. The Red Sox also sent the Cardinals a minor-league pitcher, Corey Littrell, and $1.75 million cash.