Gee Walker took a nap in St. Louis. Problem is, he did it on the base paths.

On June 30, 1934, Walker was picked off base twice in the same inning while sleep-walking for the Tigers against the Browns at Sportsman’s Park.

His blunders ruined a potential Tigers scoring threat, opening the door for the Browns to win in extra innings, and enraged Tigers player-manager Mickey Cochrane, who fined and suspended Walker.

Born to run

Gerald “Gee” Walker was an exciting ballplayer with multiple skills. He could run, hit for average and drive balls into the gaps for extra bases.

An outfielder and right-handed batter, Walker hit .300 or better in six of his 15 seasons in the majors with the Tigers (1931-37), White Sox (1938-39), Senators (1940), Indians (1941) and Reds (1942-45). He twice ranked among the top 10 in the American League in doubles, triples, RBI and total bases. He had 20 or more steals in a season five times.

At the University of Mississippi, Walker played football as well as baseball. He was a member of the “The Flying Five” backfield which also included Tadpole Smith, Rube Wilcox, Doodle Rushing and Cowboy Woodruff.

Walker brought a football-type aggressiveness to the diamond that could thrill but sometimes backfired. The Detroit News described him as a “base-running screwball” and the Detroit Free Press called it “dizzy base running.”

“He frequently was in hot water with his manager because of reckless running and his penchant for being picked off base,” The Sporting News noted.

Costly gaffes

The Tigers, who had not won a pennant since 1909, were challenging the Yankees for control of the American League in 1934. Entering a series-opening Saturday afternoon game with the Browns at St. Louis, the Tigers (40-25) were a mere half game behind the first-place Yankees (40-24). The Browns (28-34) were a team the Tigers were expected to beat, so Mickey Cochrane, Detroit’s manager and catcher, was looking for a strong start to the series.

With the score tied at 3-3, Hank Greenberg led off the Tigers’ eighth with a single. Walker followed with a grounder to third baseman Harlond Clift, who threw low trying to force out Greenberg at second.

Clift’s error gave the Tigers a scoring chance, with Greenberg at second, Walker at first, no outs and Marv Owen (who drove in 98 runs that season) at the plate.

Greenberg’s presence on second meant Walker had nowhere to go and thus didn’t need to take anything more than a normal lead, but after Jack Knott made a pitch to Owen, catcher Rollie Hemsley noticed Walker had drifted into a no-man’s land off first. Hemsley fired the ball to first baseman Jack Burns and Walker was trapped between first and second.

When Greenberg saw the predicament Walker was in, he tried to help by galloping toward third but got caught in a rundown. Before Greenberg was tagged out, Walker advanced to second. Owen then lined to left for the second out.

Though picked off once that inning, Walker wandered six feet from second base. Before making a pitch to the next batter, Knott whirled and threw to shortstop Alan Strange, covering second. Walker was caught flat-footed and tagged out, ending the inning. As the Detroit Free Press noted, Walker “broke up a rally with some of his characteristic crackpottery.”

The Browns won, 4-3, in 10 innings. Boxscore

Out of sight

“Cochrane was furious with Walker,” the Free Press reported. “Before he left the Tigers’ dugout at the end of the game, he almost blew four fuses.”

Citing Walker’s bungling on the base paths, Cochrane suspended him indefinitely and issued a fine.

“I’m through with that fellow,” Cochrane said to the Free Press. “I’ve done everything I could to help him. Then he goes and kicks away a ballgame through reckless, stupid base running. It would not be fair to the other players to keep a fellow of Walker’s type around.”

Walker told the Detroit newspaper, “I don’t blame Mickey for doing what he has done. I had it coming to me.”

(The contrite comments were in contrast to what Walker said years later. Walker said to Chicago reporter Edgar Munzel, “I thought it was a rotten deal because I had violated no baseball rule on the club. A base runner has to be given a lot of latitude. Cochrane never forgot that day … He never liked me after that.”)

The next day, Sunday, July 1, the Tigers and Browns split a doubleheader and Walker, not in uniform, watched from a box seat. Afterward, the Tigers departed by train for a series in Cleveland and Walker took a separate train back to Detroit.

“All I want to do is get that fellow out of my sight in a hurry,” Cochrane told the Free Press.

While the Tigers were splitting a doubleheader at Cleveland on Monday, July 2, Walker met with Tigers owner Frank Navin. Though it was a pleasant session, Navin told Walker he backed Cochrane’s right to fine and suspend the player.

Cochrane wanted to send Walker to the minors, but he needed to clear waivers first. When the Browns made a waiver claim for Walker, the Tigers scrapped the idea of a demotion, the Free Press reported.

After the Tigers beat the Indians at Cleveland on Tuesday, July 3, both teams headed to Detroit for a July 4 doubleheader.

Gee whiz

Walker met with Cochrane before the holiday games at Detroit and offered to make an apology to the team if given another chance. He also asked if he could work out with the club, but the request was denied. Walker watched from the stands as the Tigers and Indians split the doubleheader.

After the games, Cochrane asked his players to vote on whether Walker should be reinstated. Walker’s teammates supported his return. Cochrane then declared the suspension would end after 10 days. Because the punishment began July 1, Walker was eligible to play again July 11.

“When he returns, I’ll be for him again, provided he plays the right kind of ball,” Cochrane told the Free Press.

Three days later, on Saturday, July 7, Cochrane was the catcher when the Tigers faced the Browns at Detroit. In the first inning, Cochrane doubled, driving in a run. Then, lo and behold, Browns catcher Rollie Hemsley picked off Cochrane. He took off for third but was tagged out.

In the seventh, after Cochrane walked, Hemsley tried to pick off Cochrane again but he scrambled back to the bag in time.

The Tigers won, 4-0. Cochrane fined himself $10 for getting picked off second, the Free Press reported. Boxscore

He’s back

Although back in uniform on July 11, Walker didn’t get into a game until making a pinch-hit appearance against the Yankees’ Red Ruffing on July 13. He popped out to second.

The next day, July 14, Cochrane started Walker in center and he contributed a double, two singles and three RBI in the Tigers’ 12-11 victory at home versus the Yankees. Walker got an ovation from the crowd when he singled against Lefty Gomez in the first.

The game also was noteworthy because Lou Gehrig was listed in the starting lineup as the shortstop, batting leadoff. Gehrig was “weak from an attack of lumbago,” according to the Free Press, and was in the lineup “only long enough to extend to 1,427 the string of consecutive games in which he has played.”

After Gehrig led off the game with a single, Red Rolfe ran for him and stayed in to play shortstop. Boxscore

Walker went on to hit .300 with 20 stolen bases for the 1934 Tigers, who won the pennant, but Cochrane didn’t start him in any of the World Series games against the Cardinals. Walker was 1-for-3 in that Series as a pinch-hitter. In Game 2, his RBI-single against Bill Hallahan tied the score at 2-2. Bill Walker relieved _ and picked Walker off first. Boxscore

Most popular

Walker had outstanding seasons for the Tigers in 1936 (.353 batting average, 55 doubles, 105 runs scored) and 1937 (.335 batting average, 213 hits, 113 RBI, 105 runs scored). On Opening Day in 1937, he hit for the cycle against Cleveland. Boxscore

Walker “won the hearts of all Detroit baseball fans with his daring, hard play,” International News Service reported.

The Free Press referred to Walker as the “people’s choice” and rated him as “probably the most popular player on the Tigers.”

Thus, there was an outcry when on Dec. 2, 1937, in a trade engineered by Cochrane, the Tigers sent Walker, Marv Owen and Mike Tresh to the White Sox for Vern Kennedy, Tony Piet and Dixie Walker.

“Fans by the thousands were protesting” the trading of Gee Walker, the Associated Press reported. The angry phone calls and letters produced “the biggest fan protest in the club’s history,” according to The Sporting News.

John Lardner of the North American Newspaper Alliance noted that “Mickey Cochrane, hitherto a public monument, is being wildly reviled for trading” Walker.

Cochrane said he made the deal to get Kennedy, a pitcher who was 14-13 with a 5.09 ERA for the White Sox in 1937 after earning 21 wins the year before. “We had to have pitching, and the only way we could get it was by giving up Walker,” Cochrane told the Associated Press. “The Sox wanted him and they had the only pitcher I thought could help us.”

Asked his reaction to the trade, Walker, referring to Cochrane, said, “I am out of the doghouse for the first time in six years.”

Kennedy was 12-12 with a 5.20 ERA for the Tigers before they dealt him to the Browns in May 1939. Walker did well with the White Sox (.305 batting average in 1938; 111 RBI in 1939) before joining the Senators (96 RBI in 1940).

Walker finished his big-league career with 1,991 hits and a .294 batting average.

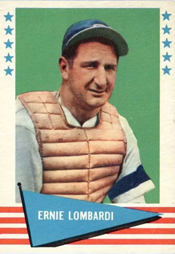

On July 6, 1934, the Reds edged the Cardinals, 16-15, at St. Louis. Lombardi, the Reds catcher and future Hall of Famer who was nicknamed “Schnozz” because of his big nose, produced five hits in five trips to the plate. Cardinals catcher Spud Davis, a career .308 hitter, was 4-for-4 with two walks.

On July 6, 1934, the Reds edged the Cardinals, 16-15, at St. Louis. Lombardi, the Reds catcher and future Hall of Famer who was nicknamed “Schnozz” because of his big nose, produced five hits in five trips to the plate. Cardinals catcher Spud Davis, a career .308 hitter, was 4-for-4 with two walks. On July 1, 1984, the Cardinals and Expos swapped utility infielders, with Chris Speier coming to St. Louis for Mike Ramsey.

On July 1, 1984, the Cardinals and Expos swapped utility infielders, with Chris Speier coming to St. Louis for Mike Ramsey.

In June 1957, the Cardinals offered the New York Giants a combination of cash and players for Mays, the St. Louis Globe-Democrat reported.

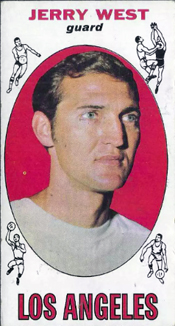

In June 1957, the Cardinals offered the New York Giants a combination of cash and players for Mays, the St. Louis Globe-Democrat reported. Whether facing the St. Louis University Billikens as a college senior or the St. Louis Hawks as a NBA rookie, West performed with excellence, totaling consistently impressive numbers of points, rebounds and assists.

Whether facing the St. Louis University Billikens as a college senior or the St. Louis Hawks as a NBA rookie, West performed with excellence, totaling consistently impressive numbers of points, rebounds and assists. In two June relief appearances Dean made for the 1934 Cardinals, National League president John Heydler credited him with wins in both, even though other pitchers appeared to qualify instead.

In two June relief appearances Dean made for the 1934 Cardinals, National League president John Heydler credited him with wins in both, even though other pitchers appeared to qualify instead.