While growing up in the St. Louis suburb of University City, Ken Holtzman rooted for the Cardinals and dreamed of pitching in the big leagues. Holtzman got to the majors, but not with the Cardinals. He went instead to their rivals, the Cubs.

A left-hander, Holtzman was a starter for the Athletics when they won three consecutive World Series titles. He also pitched two no-hitters in the National League and, as a rookie, beat his boyhood baseball idol, giving Sandy Koufax his last regular-season career loss.

A left-hander, Holtzman was a starter for the Athletics when they won three consecutive World Series titles. He also pitched two no-hitters in the National League and, as a rookie, beat his boyhood baseball idol, giving Sandy Koufax his last regular-season career loss.

Holtzman achieved 174 regular-season wins and four more in the World Series.

When he pitched the last game of his 15-year stint in the majors, it occurred, fittingly, in his hometown against the Cardinals. Afterward, Holtzman told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, “Even though I signed to play with the Cubs, my heart has always been with the Cardinals.”

Natural talent

Holtzman got his interest in baseball from his father, Henry, a machine tool dealer.

“I remember reading Jimmy Piersall’s book and how his father pushed him,” Holtzman recalled to The Sporting News. “It was nothing like that with my dad. He didn’t push me, but he used to encourage me.

“He would try to keep my mind preoccupied with sports, and especially improving myself as far as baseball was concerned. When other kids would be thinking about girls and cars after school hours, I used to go home and my father would be waiting. He would take time out from his own business. We’d go over to a park a few blocks away. He’d hit me fly balls and I’d pitch to him. He recognized I had a natural talent for baseball, but we actually worked on all sports. Pretty soon I developed my own desire to improve myself.”

Holtzman was 8 when his dad took him to his first big-league game at the former Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis. “When we walked into the old park, I thought it was the greatest thing in the world,” Holtzman told the Post-Dispatch.

As a pitcher for University City High School, Holtzman was coached during his sophomore and junior years by Ed Mickelson, a former first baseman for the Cardinals, Browns and Cubs. Mickelson’s replacement, Henry Buffa, coached University City to a state title in Holtzman’s senior year of 1963. Holtzman pitched a no-hitter and struck out 14 in the state semifinal against Springfield Hillcrest.

After his sophomore season at the University of Illinois, the Cubs chose Holtzman in the fourth round of the June 1965 amateur draft. Pitching for farm clubs, Holtzman, 19, struck out 114 in 86 innings that summer, earning a promotion to the Cubs in September. The first pitch he threw for them was walloped by the Giants’ Jim Ray Hart for a home run. Boxscore

Special games

Holtzman arranged to take classes at the University of Illinois branch campus in Chicago while pitching for the Cubs.

The first time he faced the Cardinals was on May 25, 1966, in the sixth game played at Busch Memorial Stadium in St. Louis. Several Holtzman family members were there to cheer him. “I was a little nervous at first,” Holtzman said to the Post-Dispatch. “My grandmother was seeing her first major-league game.”

Holtzman pitched well, allowing two runs in six innings, but was the losing pitcher. Boxscore

Afterward, Holtzman took a 12:19 a.m. flight to Chicago because he had an 8 a.m. French class to attend, the Post-Dispatch reported.

The next time Holtzman pitched in St. Louis, on July 17, 1966, he got the win, yielding two runs in seven innings. Two future Hall of Famers supported him. Ferguson Jenkins got the save and Billy Williams hit for the cycle. Boxscore

Some saw Holtzman, 20, as the Cubs’ version of Sandy Koufax.

“Sportswriters made the first comparison between Sandy and me, primarily, I guess, because both of us are left-handers and Jewish,” Holtzman told The Sporting News. “As far as I’m concerned, there is no comparison. He was my boyhood idol and I still regard him as the greatest I’ve ever seen. We’re miles and miles apart.”

The only time Holtzman and Koufax started against one another was on Sept. 25, 1966, at Wrigley Field in Chicago. Holtzman won, holding the Dodgers hitless until Dick Schofield led off the ninth with a single.

The pitching lines:

_ Koufax: 8 innings, 4 hits, 2 runs (one earned), 2 walks, 5 strikeouts.

_ Holtzman: 9 innings, 2 hits, 1 run, 2 walks, 8 strikeouts.

“It isn’t often Koufax loses when he holds a team to one earned run and four hits,” the Los Angeles Times noted, “but this time he was outpitched by Holtzman.”

Koufax told the newspaper, “When a guy holds you hitless for eight innings, you know he pitched a great game. I was satisfied with my performance, but Ken was too good for us today.” Boxscore

On the rise

Limited to 12 starts for the Cubs in 1967 because of military duty, Holtzman was 9-0, including a win against the Cardinals, who were on their way to becoming World Series champions. Boxscore

Holtzman also earned his degree in business administration from Illinois in 1967. He worked several winters for I.M. Simon and Company, a St. Louis securities brokerage firm, and earned accreditation from the New York Stock Exchange as a registered representative.

On Aug. 2, 1968, Holtzman pitched his third consecutive shutout, a two-hitter against the Cardinals. Using a changeup and a fastball, he limited St. Louis to singles by Julian Javier and Tim McCarver. “I feel it was the best game I ever pitched,” Holtzman said to the Post-Dispatch. “I may have had better stuff in some other game, but I think that as far as smartness and strategy, this was my best. I felt in command all the way.” Boxscore

Holtzman pitched no-hitters against the Braves (in 1969) and the Reds (in 1971), but the Cardinals gave him trouble. He was 9-14 against them. Lou Brock beat him with a walkoff home run in 1969. Boxscore Joe Torre, in 74 plate appearances versus Holtzman, had a .554 on-base percentage and .508 batting average.

After consecutive 17-win seasons in 1969 and 1970, Holtzman was 9-15 in 1971, had differences with Cubs manager Leo Durocher and sought to be traded. On Nov. 29, 1971, the Cubs dealt Holtzman to the Athletics for Rick Monday. “I wouldn’t have cared if the Cubs had traded me for two dozen eggs,” Holtzman told the Chicago Tribune.

American Leaguer

The four years Holtzman spent with the Athletics were the glory days of his career. The club won three consecutive World Series titles. Holtzman’s regular-season win totals were 19 in 1972, 21 in 1973, 19 again in 1974 and 18 in 1975.

On the eve of the 1972 World Series, Athletics manager Dick Williams said to the Oakland Tribune, “Ken has pitched superbly for us all year. You might say he saved us. Without those 19 wins, the only way the A’s would have made the World Series is by paying to get in.”

Holtzman was 4-1 in World Series games for the Athletics and hit .333, with a home run and three doubles. Video

On April 2, 1976, Holtzman and Reggie Jackson were traded to the Orioles for Don Baylor, Paul Mitchell and Mike Torrez. Two months later, Holtzman was flipped to the Yankees. He was 9-7 for them but fell into disfavor with manager Billy Martin, who didn’t use him in the playoffs or World Series that year.

Though Holtzman was healthy, Martin rarely pitched him in 1977. He worked 71.2 innings, a pittance for a pitcher who exceeded 200 innings nine times. The New York Times dubbed him the “designated sitter” and noted, “It is very likely that Holtzman sits simply because the manager doesn’t have confidence in him.”

Ignored again in 1978, Holtzman asked out and was sent to the Cubs in June.

Headed for home

The rust took a toll on Holtzman. His ERA with the 1978 Cubs was 6.11. He was better in 1979, shutting out the Astros twice, but as the season wound down he knew it would be his last.

His final big-league appearance on Sept. 19, 1979, was a start at St. Louis. Holtzman held the Cardinals scoreless. In the seventh, with two outs, a runner on base and Ted Simmons batting, Cubs manager Herman Franks wanted to lift Holtzman, but he didn’t want to leave. “I told Herman I wanted to pitch to one more man,” Holtzman said to the Post-Dispatch.

Franks relented and Holtzman retired Simmons, ending the inning. “Simmons is the best,” Holtzman told the Post-Dispatch. “At least I went out beating the best.”

After Bill Buckner batted for Holtzman in the eighth, Bruce Sutter took a 2-0 lead into the bottom of the ninth but blew the save chance, costing Holtzman a win. Boxscore

Holtzman settled in Chicago, earned a master’s degree in education at DePaul and taught in public schools.

To be close to his elderly parents, he moved to St. Louis in 1998 and became supervisor of health and physical education at the Jewish Community Center in Chesterfield, Mo. In addition to overseeing facilities and youth sports programs, Holtzman was head coach of the 9- and 10-year-old baseball teams. His assistant was his former prep coach, Ed Mickelson.

Holtzman had batting cages installed in the basement of the Jewish Community Center and during the winter Cardinals players such as Albert Pujols, J.D. Drew, Mike Matheny and John Mabry practiced their hitting there. Pitcher Gene Stechschulte came, too, to get in his throwing.

“They’re terrific with the little kids,” Holtzman told the Post-Dispatch in 2002. “Nobody bothers them as far as autographs, because people know they’re here to work. When they’re done, Pujols or Stechschulte will get in a pickup basketball game or floor hockey game with the little kids.”

During Brock’s prime years with the Cardinals, when he led the National League in stolen bases eight times, one of the most difficult catchers to steal against was Grote, who played for the Mets.

During Brock’s prime years with the Cardinals, when he led the National League in stolen bases eight times, one of the most difficult catchers to steal against was Grote, who played for the Mets. A Chicago Cubs right-hander, Warneke pitched a one-hitter on Opening Day versus the Reds and followed that with another one-hitter in his next start against Dean and the Cardinals.

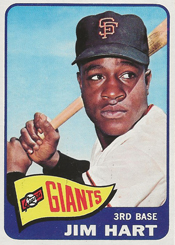

A Chicago Cubs right-hander, Warneke pitched a one-hitter on Opening Day versus the Reds and followed that with another one-hitter in his next start against Dean and the Cardinals. On his first day playing in the majors, Hart suffered a fractured left collarbone when struck by a Bob Gibson pitch.

On his first day playing in the majors, Hart suffered a fractured left collarbone when struck by a Bob Gibson pitch. Koufax, 28, was considered to be at the top of his game then, coming off a dominant season. The left-hander won both the National League Most Valuable Player and Cy Young awards in 1963. He was 25-5 that season, including 4-0 versus the Cardinals, and led the majors in wins, ERA (1.88), shutouts (11) and strikeouts (306). Koufax also won Games 1 and 4 of the 1963 World Series, a Dodgers sweep of the Yankees.

Koufax, 28, was considered to be at the top of his game then, coming off a dominant season. The left-hander won both the National League Most Valuable Player and Cy Young awards in 1963. He was 25-5 that season, including 4-0 versus the Cardinals, and led the majors in wins, ERA (1.88), shutouts (11) and strikeouts (306). Koufax also won Games 1 and 4 of the 1963 World Series, a Dodgers sweep of the Yankees. Regardless of the locale, Joaquin Andjuar, the self-proclaimed “One Tough Dominican” pitcher, could back up his image with astonishing results.

Regardless of the locale, Joaquin Andjuar, the self-proclaimed “One Tough Dominican” pitcher, could back up his image with astonishing results.