Jose DeLeon had the talent, but not the won-loss record, to be an ace. Some of it was bad luck. Some of it was bad teams. Some of it was his own doing.

DeLeon was the first Cardinals pitcher since Bob Gibson to lead the National League in strikeouts. He outdueled Roger Clemens twice in five days. Some of the game’s best hitters were helpless against him. Cal Ripken was hitless in 12 at-bats versus DeLeon. George Brett batted .091 (1-for-11) against him.

DeLeon was the first Cardinals pitcher since Bob Gibson to lead the National League in strikeouts. He outdueled Roger Clemens twice in five days. Some of the game’s best hitters were helpless against him. Cal Ripken was hitless in 12 at-bats versus DeLeon. George Brett batted .091 (1-for-11) against him.

“George Brett told me he (DeLeon) was the toughest guy he ever hit against,” Cardinals manager Whitey Herzog said to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch in 1988. “He said his stuff was nasty.”

Yet DeLeon twice had 19 losses in a season and his career record in the majors was 86-119.

A right-hander who threw four pitches (fastball, curve, forkball and slider), DeLeon pitched 13 seasons (1983-95) in the majors with the Pirates, White Sox, Cardinals, Phillies and Expos.

Playing favorites

DeLeon was 11 when he moved with his family from the Dominican Republic to Perth Amboy, N.J., in 1972. He followed baseball and adopted pitcher Mike Torrez as his favorite player. Like DeLeon, Torrez, who began his major-league career with the Cardinals, was a big right-hander.

Though he played only one season of varsity high school baseball, DeLeon, 18, was drafted by the Pirates in 1979 and called up to the majors in July 1983. In his third appearance, a start versus the Mets, he was matched against Mike Torrez.

The result was storybook. As the New York Daily News put it, “Jose DeLeon waged a brilliant pitching war with his longtime idol, Mike Torrez.”

DeLeon, 22, held the Mets hitless until Hubie Brooks lined a single with one out in the ninth. DeLeon totaled nine scoreless innings. Torrez, 36, was even better: 11 scoreless innings. Neither got a decision. The Mets won, 1-0, in the 12th. Boxscore

Torrez said to the Daily News, “I pitched well enough to win. DeLeon pitched well enough to win. Sometimes, this game can drive you batty.”

Told that DeLeon was a fan of his, Torrez replied to the newspaper, “That’s a nice compliment. He showed a lot of poise and showed he’s a big-league pitcher.”

Three weeks later, DeLeon beat the Reds, pitching a two-hit shutout and striking out 13. “He has the best forkball I’ve ever seen,” Reds shortstop Dave Concepcion told the Dayton Daily News. “It looks like a knuckleball.” Boxscore

No-win situations

DeLeon was 7-3 with the 1983 Pirates, but it would be five years before he’d have another winning season in the majors.

“I had success early, then I thought it would be easy,” DeLeon told Mike Eisenbath of the Post-Dispatch. “My arm was ready, but my mind wasn’t.”

With the 1984 Pirates, he finished 7-13, including 0-4 versus the Cardinals. The Pirates were shut out in six of his 13 losses and scored only one run in five others. On Aug. 24, 1984, DeLeon pitched a one-hitter against the Reds _ and lost, 2-0. Boxscore

The next year was worse. His 2-19 record for the 1985 Pirates included an 0-2 mark versus the Cardinals. (DeLeon never beat the Cardinals in his career.) The Pirates were held to two runs or less in 14 of his 19 losses. They averaged 2.3 runs in his 25 starts.

Nonetheless, “His problems are a combination of his being too nice a guy and relying strictly on his arm,” Pirates general manager Syd Thrift told The Pittsburgh Press. “He has to take charge from the first pitch.”

In July 1986, DeLeon was traded to the White Sox for Bobby Bonilla. His first two wins for them came against Roger Clemens, the American League Cy Young Award recipient that year. Boxscore and Boxscore

Though he was 11-12 for the 1987 White Sox, DeLeon won six of his last seven decisions, totaled more than 200 innings (206) for the first time in the big leagues and led the White Sox in strikeouts (153).

“Trying to catch his forkball is like trying to catch Charlie Hough throwing a 90 mph knuckleball,” White Sox catcher Carlton Fisk told The Pittsburgh Press.

The Cardinals saw DeLeon, 27, as a pitcher on the verge of fulfilling his potential. On Feb. 9, 1988, they sent Ricky Horton, Lance Johnson and cash to the White Sox for DeLeon.

That’s a winner

For the next two seasons, DeLeon was a winner and did things no Cardinals pitcher had done since Bob Gibson.

In 1988, DeLeon struck out 208 batters, the most for a Cardinal since Gibson had the same total in 1972. DeLeon averaged 8.2 strikeouts per nine innings. He had a 13-10 record, but the Cardinals were 20-14 in his 34 starts. In DeLeon’s 10 losses, the Cardinals scored a total of 15 runs.

(DeLeon did it all that season. In a 19-inning marathon against the Braves, he played the outfield for four innings while Jose Oquendo pitched.)

On Sept. 6, 1988, DeLeon beat the Expos with a three-hit shutout. He also doubled versus Dennis Martinez and scored the game’s lone run. Boxscore

“His forkball and curveball were really working,” Expos slugger Andres Galarraga told the Post-Dispatch. “You didn’t know what to expect.” (Galarraga, a National League batting champion, hit .061 in 33 career at-bats versus DeLeon.)

Late in the 1988 season, DeLeon pitched in Pittsburgh for the first time since the Pirates traded him. He threw a three-hitter and won. “He looks different and acts different,” The Pittsburgh Press noted. “This was not the confused, defeated, befuddled child of a man the Pirates had traded away. This was a confident, mature adult who stuck it to the Pirates.” Boxscore

The 1989 season was DeLeon’s best. He was 16-12 and had 201 strikeouts, becoming the first Cardinals pitcher since Gibson in 1968 to lead the league in fanning the most batters. DeLeon also joined Gibson as the only Cardinals pitchers then with consecutive seasons of 200 strikeouts.

Batters hit .197 versus DeLeon in 1989. Right-handed batters had the most trouble against him, hitting .146 with more than twice as many strikeouts (115) as hits (54).

“I wish I had what he had,” Scott Sanderson, an 11-game winner with the 1989 Cubs, said to the Post-Dispatch.

On April 21, 1989, DeLeon beat the Expos on a two-hit shutout. Boxscore Four months later, he did even better _ holding the Reds scoreless on one hit (a Luis Quinones broken-bat single) for 11 innings. The Cardinals, though, stranded 16 base runners and the Reds won, 2-0, in the 13th against reliever Todd Worrell. Boxscore

Down and out

DeLeon appeared headed for another good season in 1990, winning four of his first six decisions. One of those wins came against the Reds when DeLeon pitched 7.1 scoreless innings _ “The Reds appeared to be swinging at pebbles” columnist Bernie Miklasz wrote in the Post-Dispatch _ and also tripled and scored versus Tom Browning. The triple occurred when right fielder Paul O’Neill tried unsuccessfully to make a shoestring catch and the ball skipped to the warning track. “DeLeon had no choice but to leg out a slow-motion triple,” Jack Brennan of The Cincinnati Post observed. Boxscore

After beating the Expos on June 17, DeLeon’s record was 6-5. Then he went 1-14 over his last 18 starts, finishing at 7-19.

Cardinals broadcaster Mike Shannon told Bill Conlin of the Philadelphia Daily News, “Jose DeLeon defines the word ‘siesta.’ If he could just establish some intensity, there’s no doubt he could be the best pitcher in the game. He’s got the best pure stuff in our league.”

DeLeon pitched a lot better for the Cardinals in 1991 (2.71 ERA in 28 starts) but his record was 5-9. The Cardinals totaled 17 runs in his nine losses. DeLeon had the lowest run support among National League starters (3.5 runs per nine innings). “Bad luck seems to find him,” Cardinals manager Joe Torre said to the Post-Dispatch.

Back-to-back seasons like DeLeon had in 1990 and 1991 might put almost anyone into a funk. Torre and pitching coach Joe Coleman worked to boost his confidence. “I was really down,” DeLeon said to Dan O’Neill of the Post-Dispatch. “In my mind, everything was negative.”

After a strong spring training, DeLeon was named the 1992 Cardinals’ Opening Day starter. He pitched well (one run in seven innings) but the Mets won. Boxscore and video

From there, his season unraveled. In a stretch from May 22 to June 8, DeLeon lost four consecutive starts, dropping his record to 2-6, and was moved to the bullpen. The Cardinals released him on Aug. 31 and he got picked up by the Phillies.

“DeLeon is a swell fellow,” Bernie Miklasz wrote in the Post-Dispatch. “Quiet. Unobtrusive. A gentleman. Doesn’t whine. Doesn’t blame others for his problems. Doesn’t make excuses _ but he doesn’t win as many games as he should.”

The Cardinals were responsible for giving him that statistical shiner. Qualters, 18, made his big-league debut against them. He faced seven Cardinals and retired one. Six scored. His line: 0.1 innings, six runs, 162.00 ERA in his lone appearance of the 1953 regular season.

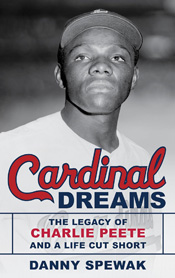

The Cardinals were responsible for giving him that statistical shiner. Qualters, 18, made his big-league debut against them. He faced seven Cardinals and retired one. Six scored. His line: 0.1 innings, six runs, 162.00 ERA in his lone appearance of the 1953 regular season. An outfielder and minor league batting champion in the Cardinals system, Peete was on the cusp of becoming a prominent player in the majors.

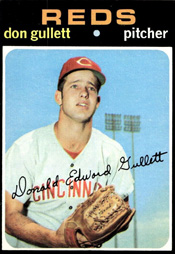

An outfielder and minor league batting champion in the Cardinals system, Peete was on the cusp of becoming a prominent player in the majors. A left-handed pitcher, Gullett was 14-3 versus the Cardinals, including 7-0 at Busch Memorial Stadium. He also liked to hit in St. Louis. His batting average there was .281.

A left-handed pitcher, Gullett was 14-3 versus the Cardinals, including 7-0 at Busch Memorial Stadium. He also liked to hit in St. Louis. His batting average there was .281. In 1968, DiMaggio was in a green and gold Oakland Athletics uniform, giving instruction to players. La Russa was trying to make the team as a reserve infielder and return to the majors for the first time in five years.

In 1968, DiMaggio was in a green and gold Oakland Athletics uniform, giving instruction to players. La Russa was trying to make the team as a reserve infielder and return to the majors for the first time in five years.