An incident involving a future Hall of Famer and a former Cardinals pitcher turned the relaxed atmosphere of an exhibition game between the Cleveland Indians and their top farm team into an awkward embarrassment.

On June 30, 1976, Cleveland’s player-manager, Frank Robinson, went to the mound and slugged Toledo reliever Bob Reynolds before 5,013 stunned spectators at the Mud Hens’ ballpark. (I was one of those in attendance.)

Robinson said Reynolds provoked him. Reynolds said Robinson was the instigator. Either way, the sight of a big-league manager punching one of the franchise’s players during a goodwill game made for a strange, ugly scene.

Hard stuff

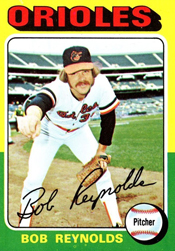

A right-handed pitcher, Bob Reynolds was nicknamed Bullet as a high school player in Seattle because of the speed of his fastball. The Giants took him in the first round of the 1966 amateur draft and sent him to Twin Falls, Idaho, to pitch for the Magic Valley Cowboys of the Pioneer League. Reynolds, 19, struck out 147 batters in 86 innings.

Unprotected in the October 1968 expansion draft, Reynolds was chosen by the Expos. At spring training, he showed “a good, live fastball,” Expos catcher Ron Brand told the Montreal Star. “Reynolds makes it hop and sail.”

On March 6, 1969, in the Expos’ first exhibition game, Reynolds retired the Royals in order in the ninth, sealing a 9-8 victory. “I was tickled to death at Reynolds’ poise,” Expos manager Gene Mauch told the Star. “He knows he can throw strikes, and he protected our lead. He really blows smoke past them, doesn’t he? He’s a hard-throwing youngster.”

Preferring he get experience at the Class AAA level, the Expos sent Reynolds to Vancouver, a farm team managed by future Hall of Famer Bob Lemon.

“I was my own worst enemy,” Reynolds told the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle. “I used to lose my head, kick dirt around the mound, throw things. Just blow up when things weren’t going right. I got to be known as a hothead. When you get a tag like that, it’s awfully hard to shake.

“In 1969 at Vancouver, I got so hot after a loss, I was ready to swing at the first person who walked in the clubhouse. Bob Lemon called me in his office, pointed to his big belly and said, ‘You want to hit something? Hit this.’ He calmed me down so much, I came out laughing at myself for my stupidity.”

The Expos called up Reynolds in September 1969. After being told he would make his big-league debut the next day in a start against the Phillies, “I took sleeping pills and everything else I could find, but nothing worked,” Reynolds recalled to the Baltimore Sun. “I was a nervous wreck the next day.”

Reynolds gave up three runs in 1.1 innings and never appeared in the regular season for the Expos again. Boxscore

Traveling man

On June 15, 1971, the Cardinals acquired Reynolds from the Expos for Mike Torrez. “We’d already lost Reynolds because his options had run out and he was frozen on Winnipeg’s roster,” Expos general manager Jim Fanning said to the Montreal Star. “A lot of clubs were interested in him and we decided to take the first good offer. Torrez became available … and we grabbed him.”

Cardinals scout Joe Monahan told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, “Reynolds should be able to help us … His control has improved since the Expos sent him to Winnipeg because they made him stick to his fastball and slider, and forget about his curve.”

Reynolds made four relief appearances for the 1971 Cardinals and gave up runs in three of those games. As the Post-Dispatch noted, “Reynolds made little noise on the Cardinals scene except when he flapped his arms and gave his crow call. The bird imitation kept the bullpen crew from falling asleep.”

Two months after he joined the Cardinals, Reynolds was dealt to the Brewers. A Brewers instructor, former big-league pitcher Wes Stock, helped Reynolds with his slider. “Stock got me to come over the top with it,” Reynolds told the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle. “I had been coming down the side a little with it and it was a flat slider.”

Reynolds was on the move again the following March when the Brewers sent him to the Orioles, who assigned him to their Rochester farm team. Working mostly in relief, he had a 1.71 ERA and struck out 107 in 95 innings. The Orioles brought him back to the majors in September 1972.

Doggone it

At spring training in 1973, Reynolds suffered a hairline fracture in his right hand and dislocated the little finger when he fell against a wall in his apartment while playing with his dog.

“I can’t blame it on the dog,” Reynolds said to the Baltimore Sun. “It was me who suggested the game in the first place.

“Reminds me of the time I was playing high school basketball and I tried to jazz it up as I went in for a layup. The ball got stuck behind my back and in trying to get straightened out I ran into a wall. Nearly knocked myself cold. Fans thought it was great. Coach didn’t like it too much.”

For the next two years (1973-74), Reynolds was the Orioles’ top right-handed reliever. He had a 1.95 ERA in 1973 and his nine saves tied left-hander Grant Jackson for the team lead. In 1974, Reynolds led the Orioles in games pitched (54) and had a 2.73 ERA.

At the urging of manager Earl Weaver, Reynolds was traded to the Tigers for pitcher Fred Holdsworth in May 1975. Three months later, the Cleveland Indians claimed Reynolds off waivers.

Missing the cut

At Indians spring training in 1976, the final spot on the pitching staff came down to a choice between Reynolds and Stan Thomas. “Bullet is faster, but his ball is straighter,” catcher Ray Fosse told the Akron Beacon Journal. “Thomas’ ball moves more and he has a greater selection of pitches.”

Frank Robinson and general manager Phil Seghi chose Thomas. “It was difficult having to make a decision like this,” Robinson said to the Akron newspaper. “Reynolds has a good attitude. He did everything we asked him to do.”

Reynolds, 29, was assigned to Toledo. Because he had no more options, he would need to remain on the Mud Hens’ roster all season.

The 1976 season was the last for Frank Robinson as a player and his second as a big-league manager. (He would finish with 586 career home runs and get elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame.) The Indians, who had a streak of seven straight losing seasons, seemed to be improving under Robinson. Their record was 36-33 when they went to play the exhibition game with Toledo.

On the warpath

Among those in the Indians’ starting lineup on a rainy evening for the Toledo game were Boog Powell at first base, Duane Kuiper at second, George Hendrick in left and Rico Carty as the designated hitter. The Mud Hens had the likes of catcher Rick Cerone and first baseman Joe Lis.

Robinson began substituting in the third inning. He sent coach Rocky Colavito, 42, to replace Hendrick in left. Another coach, Jeff Torborg, got to play, too. Robinson put himself in the game as a pinch-hitter in the fifth. Reynolds, who relieved Cardell Camper (a former Cardinals prospect), was on the mound for Toledo.

Reynolds’ first pitch to Robinson went about six feet over his head. “That was no accident,” Robinson told the Associated Press. “I’ve played long enough to know. The first inning he pitched he never threw a ball above the waist and he never threw one above the waist to the batter before me.”

Robinson said to United Press International, “I feel he was trying to intimidate me and show (off) in front of his teammates.”

(“I wasn’t throwing at him,” Reynolds said to Ron Maly of the Des Moines Register. “The ball just got away from me. I was trying to throw a fastball and my spikes were cluttered with mud.”)

The at-bat continued and Robinson hit a fly ball that was caught for an out. As Robinson cut across the diamond to return to the dugout on the third base side, he said to Reynolds, “You got a lot of guts throwing at me in a game like this,” United Press International reported.

According to Robinson, Reynolds replied, “You had a lot of guts sending me down, you (obscenity).”

Robinson rushed toward Reynolds and punched him with a left-right combination. The left struck Reynolds in the teeth and jaw. The right “sent Reynolds to the ground in a sitting position,” The Cleveland Press reported.

Reynolds told the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle that he blanked out “momentarily, maybe for just a second.”

Robinson was ejected and booed by the Toledo fans. Reynolds, spitting blood, insisted on staying in the game. His tongue was cut and his jaw was swollen, according to The Cleveland Press.

“The whole thing could have been avoided,” Toledo manager Joe Sparks said to the Des Moines Register. “The manager of a big-league club should go out of his way to not let something like that happen.”

Robinson told United Press International, “If the circumstances were the same, I would do it again.”

Cleveland won the exhibition game, 13-1. Right fielder Charlie Spikes, who would total three home runs for the Indians in 1976, hit three homers against Toledo. In the seventh inning, Ray Fosse also hit a home run for Cleveland but injured a knee during his trot around the bases. Pitching coach Harvey Haddix, 50, had to come in and complete circling the bases for Fosse.

Robinson went on to manage 17 seasons in the majors with the Indians, Giants, Orioles, Expos and Nationals. Reynolds never got back to the big leagues.

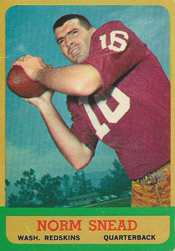

A classic drop-back passer, Snead was 6-foot-4, smart and had a strong arm. Teams traded quarterbacks Sonny Jurgensen and Fran Tarkenton to acquire him.

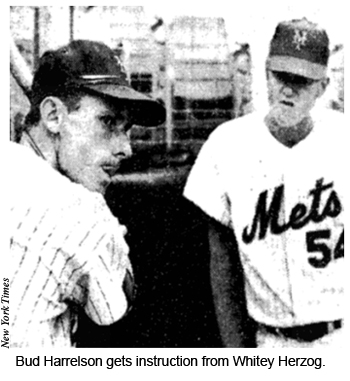

A classic drop-back passer, Snead was 6-foot-4, smart and had a strong arm. Teams traded quarterbacks Sonny Jurgensen and Fran Tarkenton to acquire him. In 16 big-league seasons, Harrelson hit .236 and had a modest on-base percentage of .327. Against Gibson, he turned into the reincarnation of Ty Cobb. Harrelson batted .333 versus the Cardinals ace and, with 20 hits and 14 walks, had a .459 on-base percentage.

In 16 big-league seasons, Harrelson hit .236 and had a modest on-base percentage of .327. Against Gibson, he turned into the reincarnation of Ty Cobb. Harrelson batted .333 versus the Cardinals ace and, with 20 hits and 14 walks, had a .459 on-base percentage.

In his 13 seasons (1958-70) in the NFL with the Los Angeles Rams, Cleveland Browns and Washington Redskins, Ryan had more ups than downs versus the Cardinals but it wasn’t easy. He started 12 games against them and was intercepted 14 times. No other team picked off more of his passes.

In his 13 seasons (1958-70) in the NFL with the Los Angeles Rams, Cleveland Browns and Washington Redskins, Ryan had more ups than downs versus the Cardinals but it wasn’t easy. He started 12 games against them and was intercepted 14 times. No other team picked off more of his passes. Sewell went hunting with a group in Florida’s Ocala National Forest on that day, the last of deer season.

Sewell went hunting with a group in Florida’s Ocala National Forest on that day, the last of deer season.