When Larry Miggins was a student at Fordham Prep in the Bronx in the early 1940s, he told a classmate he wanted to be a big-league baseball player. The classmate, Vin Scully, told Miggins he wanted to be a big-league baseball broadcaster. The boys ruminated about the possibility of Scully broadcasting a game Miggins played in.

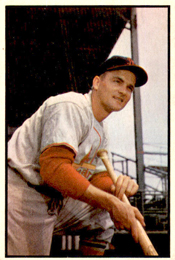

A decade later, in 1952, Miggins was in the big leagues as a rookie reserve left fielder for the Cardinals. Scully was in his third year as a Dodgers broadcaster.

A decade later, in 1952, Miggins was in the big leagues as a rookie reserve left fielder for the Cardinals. Scully was in his third year as a Dodgers broadcaster.

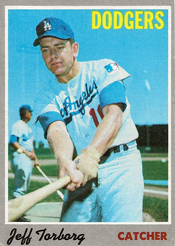

On May 13, 1952, Miggins was in the starting lineup for a game at Brooklyn against the Dodgers. It was the first game he played at Ebbets Field. Scully was the junior member of a three-man broadcasting crew doing the game that day. Red Barber and Connie Desmond were the more experienced broadcasters.

When Miggins struck out in his first plate appearance of the game in the second inning, Scully was not on the air.

Two innings later, though, he was doing the broadcast when Miggins stepped to the plate against Preacher Roe. Scully had the call when Miggins belted a pitch into the seats in left for his first home run in the majors. Boxscore

Decades later, in recalling the moment for an audience at the Ronald Reagan Library in Simi Valley, Calif., Scully said, “It was probably the toughest home run call I’ve ever had because (the dream) came true,” the Ventura County Star reported. “Don’t be afraid to dream.”

Traveling man

A son of Irish immigrants, Larry Miggins was the valedictorian of the class of 1943 at Fordham Prep. He enrolled at the University of Pittsburgh, but in December 1943, when his boyhood favorites, the New York Giants, offered him a contract, he left college and signed with them.

Miggins, 18, played eight games for the Giants’ Jersey City farm club in April 1944, then joined the United States Merchant Marine. He was discharged in time to play the 1946 minor-league season and was in the lineup for Jersey City when Jackie Robinson played his first game in the Dodgers’ system for Montreal. You Tube Audio interview

A 6-foot-4 right-handed batter with power, Miggins slugged 22 home runs in the minors in 1947, but the Giants left him off their big-league winter roster. Rated by Cardinals scouts “as one of the best prospects in the minors, possessing speed and a good arm,” according to The Sporting News, Miggins was selected by St. Louis in the November 1947 draft of unprotected players.

The transaction stunned Miggins, who “always thought he was going to play with the Giants,” the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported.

Three days before the Cardinals’ 1948 season opener, Miggins was placed on waivers and claimed by the Cubs. According to the Associated Press, he drove to Chicago in a 1931 jalopy, parked at Wrigley Field, and joined the Cubs on their trip to Pittsburgh, where they opened the season against the Pirates.

Miggins, who didn’t play in any of the three games at Pittsburgh, returned to Chicago with the Cubs on April 23 and was summoned to the Wrigley Field office. He was told the Cubs had placed him on waivers and he was reclaimed by the Cardinals. On his way out, the Associated Press noted, he was asked to move his crate from club owner Phil Wrigley’s private parking space.

The Cardinals assigned Miggins to their Class A farm team at Omaha and he hit 26 home runs in 97 games. “Uses his wrists well,” Omaha manager Ollie Vanek told the Omaha World-Herald. “Watches the pitches with keen discrimination and rarely offers at a bad one. He has a follow-through, and a stance. Miggins can hit that low curve, which is one of the hardest things to do in baseball.”

The Irish lad from the Bronx also had “a lilting voice and likes to entertain his teammates with songs,” The Sporting News reported.

Called up to the Cardinals in September 1948, Miggins got into one game, making his big-league debut as a pinch-hitter against the Cubs and scoring after reaching base on an error. Boxscore

Family man

Miggins spent the next three seasons (1949-51) in the minors. With Houston, he hit 21 home runs in 1949 and 27 in 1951.

“Miggins is big and strong and fast, and while his quiet manner and impeccable behavior may give some the impression that he lacks aggressiveness, he has a burning desire to play big-league baseball,” the Post-Dispatch reported.

During the winters, Miggins took college courses and earned a bachelor’s degree from the University of St. Thomas in Houston.

In 1952, Eddie Stanky’s first year as manager, Miggins, 26, made the Cardinals’ Opening Day roster as a backup left fielder and pinch-hitter. He didn’t play much. The highlights were the home run in Brooklyn with Vin Scully at the microphone and a home run against a future Hall of Famer, Warren Spahn of the Braves. Boxscore

“Larry Miggins could do it,” Cardinals owner Fred Saigh said to the St. Louis Globe-Democrat. “He has all the equipment. He’s a wonderful boy, one of the best in our organization, and that’s the trouble. If he could get just a little more determination, he could make it.”

Miggins hit .229 in 96 at-bats for the 1952 Cardinals. He spent the next two seasons in the minors, then left baseball when a Houston judge, Allen B. Hannay, approached him about a government job in probation and parole.

With the judge’s encouragement, Miggins earned a master’s degree in criminology from Sam Houston State and had a long career as a probation and parole officer.

Miggins and his wife, Kathleen, had 12 children, four girls and eight boys. With a touch o’ the blarney, Miggins explained to blogger Bill McCurdy, “Kathleen was hard of hearing. Every night we went to bed as I was turning out the light, I would softly whisper to Kathleen, ‘Are you ready to go to sleep or what?’ She gave me the same answer every time: ‘What?’ “

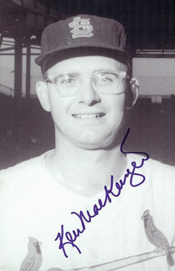

Doing the unexpected came naturally to MacKenzie. A hockey player from a small town on a Canadian island, he went to Yale, graduated and became a big-league pitcher.

Doing the unexpected came naturally to MacKenzie. A hockey player from a small town on a Canadian island, he went to Yale, graduated and became a big-league pitcher. In the 1940s, the Cardinals (four) and Dodgers (three) won seven of the 10 National League pennants that decade. Casey was a prominent pitcher on the Dodgers championship clubs in 1941 (14 wins, seven saves) and 1947 (10 wins, 18 saves).

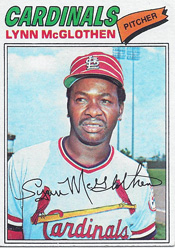

In the 1940s, the Cardinals (four) and Dodgers (three) won seven of the 10 National League pennants that decade. Casey was a prominent pitcher on the Dodgers championship clubs in 1941 (14 wins, seven saves) and 1947 (10 wins, 18 saves). On Dec. 7, 1973, the Cardinals acquired John Curtis, Mike Garman and Lynn McGlothen from the Red Sox for Reggie Cleveland, Diego Segui and Terry Hughes. It was the second major trade between the teams since the end of the season. Two months earlier,

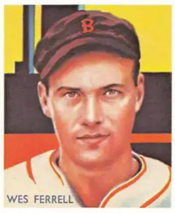

On Dec. 7, 1973, the Cardinals acquired John Curtis, Mike Garman and Lynn McGlothen from the Red Sox for Reggie Cleveland, Diego Segui and Terry Hughes. It was the second major trade between the teams since the end of the season. Two months earlier,  A right-hander, Ferrell holds the record for regular-season career home runs hit by a pitcher. According to baseball-reference.com, the top six are Ferrell (38), Bob Lemon (37), Warren Spahn (35), Red Ruffing (34), Earl Wilson (33) and Don Drysdale (29).

A right-hander, Ferrell holds the record for regular-season career home runs hit by a pitcher. According to baseball-reference.com, the top six are Ferrell (38), Bob Lemon (37), Warren Spahn (35), Red Ruffing (34), Earl Wilson (33) and Don Drysdale (29).