For pitcher Pete Richert, fatigues became as much a part of his wardrobe as a baseball uniform in 1968.

In April, he served with the National Guard, trying to quell riots in Washington, D.C. In the fall, he went to Vietnam, looking to boost the spirits of U.S. troops. In between, he pitched in relief for the Baltimore Orioles.

In April, he served with the National Guard, trying to quell riots in Washington, D.C. In the fall, he went to Vietnam, looking to boost the spirits of U.S. troops. In between, he pitched in relief for the Baltimore Orioles.

Among those who accompanied Richert to Vietnam was Cardinals general manager Bing Devine. Five years later, on Dec. 5, 1973, Devine acquired Richert for the Cardinals in a trade with the Dodgers.

A left-hander, Richert was a two-time American League all-star and pitched on Orioles teams that won three pennants and a World Series title. His stint with the Cardinals, though, didn’t go the way either he or the team had hoped it would.

Blazing heat

Richert was from Floral Park, N.Y., a village on Long Island. He went to Sewanhaka High School. (The name translates to “island of shells.”) Its alumni also include actor Telly Savalas and Heisman Trophy winner Vinny Testaverde.

In August 1957, Richert, 17, signed with the Brooklyn Dodgers, the day before the club declared it was moving to Los Angeles after the season.

Richert steadily worked his way through the Dodgers’ farm system as a starting pitcher. In 1960, for the Class AA Atlanta Crackers managed by Rube Walker, Richert had 19 wins and struck out 251 batters in 225 innings. The Atlanta Journal called him “the Cracker with the golden arm” and described his best pitch as a “miracle whip fastball.”

He was 22 when he made a spectacular big-league debut with the Dodgers on April 12, 1962. Relieving Stan Williams, Richert struck out the first six batters he faced _ Vada Pinson, Frank Robinson, Gordy Coleman (who advanced to first on a passed ball by John Roseboro), Wally Post, Johnny Edwards and Tommy Harper. Boxscore

(Until then, the only pitcher to strike out six consecutive batters in his debut in the majors was the Dodgers’ Karl Spooner against the Giants in 1954. Boxscore)

“I always say a little prayer when I’m nervous and excited, and I was tonight as I started walking to the mound,” Richert told the Los Angeles Times. “My father, who always wanted me to be a baseball player, died when I was 15. When I decided to try baseball, my brother told me that when I was nervous or excited to always say a prayer and dad would help me. As soon as I threw a pitch to Pinson, the nervousness left me.”

Called upon three days later, Richert struck out five, including Joe Torre twice, in two innings against the Braves. Boxscore

Setback in St. Louis

Richert’s robust rookie season got derailed on May 12, 1962, at St. Louis. Relieving in the 11th, he allowed no runs or hits to the Cardinals in 2.2 innings. Then, as Richert pitched to Bill White with two outs in the 13th, “the ball bounced to the plate, his glove sailed 15 feet away and he grabbed his left elbow in obvious agony,” The Sporting News reported.

Taken to a hospital, it was discovered Richert had tore ligaments in the elbow. Boxscore

He came off the disabled list two months later and was sent to the Dodgers’ Omaha farm team. Worried about reinjuring his arm, Richert resisted throwing hard. According to the New York Times, Omaha manager Danny Ozark said to Richert, “Pete, you’re scared to throw the ball. If you’re going to be a pitcher, you’ve got to make up your mind. It’s the difference between spending the rest of your life in the minors or going back to the big time.”

Richert responded, got brought back to the Dodgers in August and was put into their starting rotation.

He split each of the next two seasons (1963-64) between the Dodgers and their Spokane farm team (managed by Danny Ozark).

On Sept. 16, 1963, the first-place Dodgers went to St. Louis for a three-game showdown series with the Cardinals, who were a game behind them. Dodgers manager Walt Alston opted to start three left-handers. After Johnny Podres and Sandy Koufax prevailed in the first two games, Richert started the finale. He was knocked out in the third inning but the Dodgers got brilliant relief from another left-hander, Ron Perranoski, and completed the sweep. Boxscore

Capital gains

In December 1964, the Dodgers sent Richert to the Washington Senators. The trade reunited him with his former Atlanta manager, Rube Walker, who was a coach on the staff of Senators manager Gil Hodges.

Richert led the 1965 Senators in wins (15), ERA (2.60), innings pitched (194) and strikeouts (161). He also pitched two scoreless innings for the American League in the All-Star Game, striking out Willie Mays and Willie Stargell. Boxscore

He was the Opening Day starter for Washington in 1966 when Emmett Ashford became the first black umpire in the majors. Boxscore

On April 24, 1966, Richert struck out seven consecutive Tigers batters _ Don Demeter, Ray Oyler, Orlando McFarlane, Bill Monbouquette, Dick Tracewski, Don Wert and Norm Cash. Boxscore

Named again to the all-star team, Richert pitched in the 1966 game at St. Louis and gave up the game-winning hit to former teammate Maury Wills. Boxscore

Richert led the 1966 Senators in wins (14), innings pitched (245.2) and strikeouts (195). He was the first Washington Senators pitcher to strike out 195 in a season since Walter Johnson (228) in 1916.

War zones

Sent by the Senators to the Orioles in May 1967, Richert was moved to the bullpen in 1968 and never went back to starting.

Richert was a reservist with a National Guard unit in Washington, D.C. When rioting broke out there after Martin Luther King Jr. was murdered, Richert left the Orioles to join his outfit. His two weeks of emergency riot-control duty “consisted of street patrol with D.C. police, guarding the Washington jail and protecting firefighters,” the Baltimore Sun reported.

“I saw some things you couldn’t believe,” Richert said to the Sun. “The city and its destruction, burning, looting, violence … Two entire streets of 15 blocks and another 22-block street were leveled … Firemen would be fighting fires and there were arsonists throwing Molotov cocktails at the fire trucks.”

After the 1968 baseball season, in a trip arranged by the United Service Organizations (USO) and the baseball commissioner’s office, Richert went to Vietnam with Bing Devine, players Ernie Banks of the Cubs, Larry Jackson of the Phillies and Ron Swoboda of the Mets, and St. Louis publicist Al Fleishman.

“We’d fly by helicopter to a firebase (artillery post), spend a couple hours chatting with the men, then take off and fly to another post nearby,” Fleishman told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. “We hit five or six small bases a day that way for 17 days.”

In his memoirs, Devine recalled, “One time, we were in a whaleboat going up this canal … They gave me a grenade launcher” in case of an ambush.

Devine told the soldiers, “I don’t know how to shoot a gun. If I need it, we’re hopeless.”

Richert said to the Baltimore Sun, “We visited 57 hospitals and they figured the six of us came in contact with better than 10,000 troops.”

According to the Post-Dispatch, Richert and Devine bonded during the Vietnam trip and exchanged Christmas cards each year after that.

Fall classics

Richert’s first World Series appearance came in 1969. With the score tied in Game 4, the Mets had runners on first and second, none out, in the bottom of the 10th when Richert relieved Dick Hall. His first pitch to J.C. Martin was bunted along the first-base line. Richert got to it but his throw hit Martin in the wrist and the ball rolled away, enabling Rod Gaspar to score from second with the winning run. Photos showed Martin interfered by running inside the base line and should have been called out, the Baltimore Sun reported. Boxscore Video

Richert had a better experience in Game 1 of the 1970 World Series. In the bottom of the ninth, with Pete Rose on first and two outs, Richert relieved Jim Palmer, looking to protect a 4-3 lead. His first pitch jammed Bobby Tolan, who hit a soft liner to shortstop Mark Belanger for the final out. Boxscore

On the move

In December 1971, Richert was reunited with the Dodgers when they acquired him from the Orioles.

Two years later, when the Dodgers dealt for closer Mike Marshall, they deemed Richert expendable and traded him to the Cardinals for Tommie Agee.

Richert, 34, joined Al Hrabosky and Rich Folkers as left-handers in the bullpen for the 1974 Cardinals, but he lacked command of his fastball, walking 11 in 11.1 innings. The highlight was the save he earned when he retired the Pirates’ Al Oliver with the potential tying runs on base. Boxscore

Placed on waivers in June 1974, Richert was claimed by the Phillies at the urging of their manager, Danny Ozark.

In 21 appearances for the 1974 Phillies, Richert was 2-1 (the loss was to the Cardinals) with a 2.21 ERA. In September, it was discovered he had a blood clot in his left arm and needed surgery, bringing an end to his pitching days.

Yet, the 1982 Cardinals may be the franchise’s greatest team since baseball went to a divisional alignment. Since 1969, the only Cardinals club to finish a regular season with the best record in the National League and win a World Series title was the 1982 team.

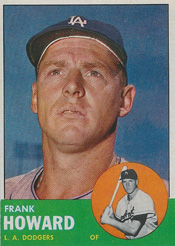

Yet, the 1982 Cardinals may be the franchise’s greatest team since baseball went to a divisional alignment. Since 1969, the only Cardinals club to finish a regular season with the best record in the National League and win a World Series title was the 1982 team. As Jim Murray of the Los Angeles Times noted, “He’s Gulliver in a baseball suit.”

As Jim Murray of the Los Angeles Times noted, “He’s Gulliver in a baseball suit.”