(Updated Jan. 9, 2025)

A couple of Hoosiers made life miserable in Brooklyn for the Cardinals.

In 1953, the Cardinals were 0-11 for the season against the Dodgers at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn’s Flatbush section.

In 1953, the Cardinals were 0-11 for the season against the Dodgers at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn’s Flatbush section.

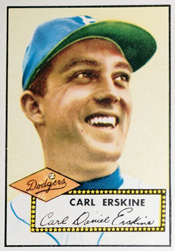

The players most responsible for the Cardinals’ troubles there were pitcher Carl Erskine of Anderson, Ind., and first baseman Gil Hodges of Princeton, Ind.

Dominant Dodgers

The 1953 Brooklyn Dodgers, subjects of the Roger Kahn book, “The Boys of Summer,” were a powerhouse, featuring a lineup with five future Hall of Famers _ Roy Campanella, Gil Hodges, Pee Wee Reese, Jackie Robinson and Duke Snider.

They rolled to the National League pennant with a 105-49 mark, finishing 13 games ahead of the runner-up Braves (92-62) and 22 ahead of St. Louis (83-71).

The Cardinals won seven of 11 against the 1953 Dodgers at St. Louis, but it was a much different story at Brooklyn. Not only did they lose all 11 games at Ebbets Field, they often got crushed. The Dodgers outscored them, 109 to 36, in those 11 games at Brooklyn.

The Cardinals were beaten by scores of 10-1 on June 7, 9-2 on July 16, 14-0 on July 17, 14-6 on July 18, 20-4 on Aug. 30 and 12-5 on Sept. 1.

There were two one-run games, the Dodgers winning both by scores of 5-4. The cruelest for the Cardinals was on June 6, when Hodges wiped out a 4-2 St. Louis lead with a three-run walkoff home run versus Stu Miller in the ninth. Boxscore

Home sweet home

Many players contributed to the Dodgers’ perfect home record against the Cardinals in 1953, but Erskine and Hodges did the most damage.

A right-hander who mixed an overhand curve and changeup with his fastball, Erskine, 26, was nearly unbeatable at Ebbets Field that year. He ended the regular season with a home record of 12-1, including 4-0 versus the Cardinals. All four of his home wins against St. Louis were complete games.

Erskine also won Game 3 of the 1953 World Series at Ebbets Field, setting a record by striking out 14 Yankees batters, including Mickey Mantle four times. “Erskine made the Yankees look like blind men swatting at wasps,” J. Roy Stockton reported in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Boxscore

(Since then, the only pitchers with more strikeouts in a World Series game are Bob Gibson, who fanned 17 Tigers in Game 1 in 1968, and Sandy Koufax, who struck out 15 Yankees in Game 1 in 1963.)

“Look, up in the sky….”

When Erskine beat the Cardinals with a five-hitter on May 6, 1953, at Brooklyn, it was his seventh consecutive win against them, dating back to September 1950. Erskine went undefeated versus the Cardinals in 1951 (4-0) and 1952 (2-0). Boxscore

The streak was snapped a week later, May 14, 1953, at St. Louis when Erskine was knocked out in the first inning without retiring a batter. “He had no control, no stuff and no outs,” Dick Young reported in the New York Daily News. “He warmed up for 15 minutes and pitched for five.” Boxscore

Back in Brooklyn, Erskine ducked into a phone booth, donned his Superman cape and beat the Cardinals for the second time in 1953, a four-hitter in a 10-1 rout on June 7. “It was the sort of affair that grew progressively more one-sided and monotonous, finally reaching the stage where many of the fans amused themselves by launching paper planes onto the field,” Dick Young reported. “Some of these came close to hitting Erskine. So did the Cardinals, but not many succeeded.” Boxscore

A month later, Erskine beat the Cardinals at Brooklyn for a third time, even though he gave up nine hits and two walks, threw a wild pitch and committed two errors. Boxscore

Erskine’s fourth home win against the 1953 Cardinals, on Aug. 30, also was his 13th consecutive win at Ebbets Field. Erskine contributed three RBI and scored a run. Boxscore

“Some pitchers were spooked by the thought of working in Ebbets Field with its cozy fences, but not Erskine,” the New York Times noted.

(In his next start, the Braves gave Erskine his lone home loss of 1953. With the score tied at 1-1 in the eighth, Eddie Mathews hit a three-run home run and Jim Pendleton had a two-run shot. Boxscore)

Erskine finished 1953 with a regular-season record of 20-6, including 6-2 versus the Cardinals.

For his career with the Dodgers, Erskine was 122-78, including 66-28 at Brooklyn. He was 23-8 against the Cardinals _ 13-2 at Ebbets Field.

(Erskine’s second win in the majors came against the Cardinals in a 1948 relief appearance. In the book “We Would Have Played For Nothing,” Erskine recalled, “I beat Howie Pollet and he waited for me after the game in the runway to congratulate me. He said, ‘I like the way you throw.’ He was a class act. I think he identified with me because he had a unique pitch _ a straight change _ and I could throw that pitch.” Boxscore)

Among the Cardinals regularly baffled by Erskine were Enos Slaughter (.162 batting average against) and Red Schoendienst (.211). The exception, naturally, was Stan Musial. He batted .336 with eight home runs versus Erskine. According to Time Magazine, Erskine said, “I’ve had pretty good success with Stan by throwing him my best pitch and backing up third.”

In July 2023, Erskine, 96, recalled to Tyler Kepner of the New York Times that Musial “almost never missed a swing. He always hit the ball somewhere.”

In his book, “Stan Musial: The Man’s Own Story,” Musial said, “Erskine had control, a remarkable changeup and a great overhand curve.”

(Erskine had an association with the Cardinals in 1971 when he joined play-by-play men Jack Buck and Jim Woods as a guest analyst on select telecasts of games on KSD-TV Channel 5 in St. Louis.)

Lots of lumber

Three pitchers _ Stu Miller (0-3), Joe Presko (0-3) and Gerry Staley (0-2) _ accounted for eight of the 11 Cardinals losses at Ebbets Field in 1953.

Dodgers hitters were led by Gil Hodges, who had eight home runs and 23 RBI against Cardinals pitching in the 11 games at Brooklyn. Hodges had 16 hits and seven walks in those games.

(In 31 at-bats at St. Louis in 1953, Hodges had no home runs, no RBI and batted .129.)

Others who hammered the 1953 Cardinals at Ebbets Field were Roy Campanella (18 hits, 18 RBI), Jackie Robinson (18 hits, 11 RBI) and Duke Snider (four home runs and 11 RBI).

Matched against Steve Carlton and facing a lineup with Pete Rose, Joe Morgan and Mike Schmidt, Cox pitched 10 scoreless innings versus the Phillies in his big-league debut on Aug. 6, 1983.

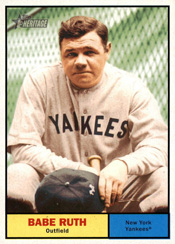

Matched against Steve Carlton and facing a lineup with Pete Rose, Joe Morgan and Mike Schmidt, Cox pitched 10 scoreless innings versus the Phillies in his big-league debut on Aug. 6, 1983. After finishing last in the eight-team American League in 1937, the Browns were looking for a manager and Babe Ruth wanted the job.

After finishing last in the eight-team American League in 1937, the Browns were looking for a manager and Babe Ruth wanted the job. Duke Carmel certainly fit the part. He was named after Duke Snider, had the mannerisms of Ted Williams and could hit with the power of Mickey Mantle.

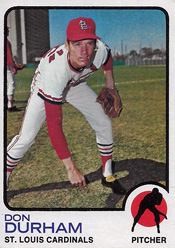

Duke Carmel certainly fit the part. He was named after Duke Snider, had the mannerisms of Ted Williams and could hit with the power of Mickey Mantle. A rookie right-hander with St. Louis in 1972, Durham had as many home runs (two) as wins (two). He batted .500 (seven hits in 14 at-bats) and had a slugging percentage of .929.

A rookie right-hander with St. Louis in 1972, Durham had as many home runs (two) as wins (two). He batted .500 (seven hits in 14 at-bats) and had a slugging percentage of .929. On July 10, 1923, Stuart started both games of a doubleheader for the Cardinals against the Braves and earned complete-game wins in both.

On July 10, 1923, Stuart started both games of a doubleheader for the Cardinals against the Braves and earned complete-game wins in both.