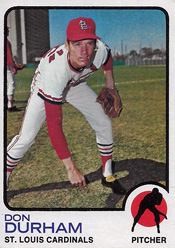

On a team with little pop, pitcher Don Durham qualified as somewhat of a slugger for the Cardinals.

A rookie right-hander with St. Louis in 1972, Durham had as many home runs (two) as wins (two). He batted .500 (seven hits in 14 at-bats) and had a slugging percentage of .929.

A rookie right-hander with St. Louis in 1972, Durham had as many home runs (two) as wins (two). He batted .500 (seven hits in 14 at-bats) and had a slugging percentage of .929.

Durham was part of a Cardinals pitching trio, along with Bob Gibson and Rick Wise, that provided as much power as some of the infielders and outfielders.

Gibson (five), Durham (two) and Wise (one) combined for eight home runs on a club that ranked last in the 12-team National League in home runs (70) in 1972.

Catcher Ted Simmons (16) and third baseman Joe Torre (11) were the lone 1972 Cardinals to reach double digits in home runs. They and outfielder Bernie Carbo (seven) were the only Cardinals with more home runs than Gibson that year.

Even Durham, with his two in 14 at-bats, had as many home runs as second baseman Ted Sizemore (two in 439 at-bats) and center fielder Jose Cruz (two in 332 at-bats), and more than shortstop Dal Maxvill (one in 276 at-bats) and third baseman Ken Reitz (none in 78 at-bats).

Promising prospect

Though born in Kentucky, Durham was a resident of the Ohio village of Arlington Heights near Cincinnati between the ages of 6 and 9, according to the Cincinnati Enquirer. He played Little League baseball there and faithfully followed the 1950s Reds, The Sporting News reported,

At Western Kentucky University, Durham was a first baseman and pitcher. Though slender at 6 feet and less than 170 pounds, he threw hard and hit for power.

In a 1969 doubleheader versus Austin Peay, Durham started and won the first game, then belted a grand slam to help Western Kentucky complete the sweep, according to The Park City Daily News of Bowling Green, Ky. A year later, he struck out 14 in pitching a no-hitter against Bellarmine. Durham led the team in hitting (.418) his final season, according to The Sporting News.

On the recommendation of scout Mo Mozzali (who signed Ted Simmons three years earlier), the Cardinals chose Durham in the seventh round of the 1970 draft. After a strong season with Class A Modesto in 1971 (13-7, 2.80 ERA, 202 strikeouts in 177 innings, plus a .240 batting average), the Cardinals decided Durham should bypass Class AA and move to Class AAA Tulsa in 1972.

On June 3, 1972, Durham pitched a shutout and hit a home run against Indianapolis. The two-run homer came after Durham fouled off two pitches trying to bunt and then was told by manager Jack Krol to swing away. “I’ve always been proud of my hitting,” Durham said to the Tulsa World.

Four days later, with Tulsa ahead, 1-0, in the last of the ninth inning at Evansville, Durham needed one out to complete a no-hitter, but Bob Coluccio grounded a single to left. Exasperated, Durham flung his glove into the air. After a brief discussion with Krol on the mound, Durham faced Darrell Porter, who the night before lined a two-out, two-run home run in the bottom of the ninth to lift Evansville to a 4-2 victory.

On Durham’s first pitch to him, Porter lofted a high fly that carried over the fence, barely beyond the reach of right fielder Bob Wissler, for a game-winning home run. “To tell you the truth, I didn’t think I hit the ball that good,” Porter said to Tom Tuley of The Evansville Press. “I thought it was going to be caught.”

Sitting alone on the dugout steps after going from possible no-hitter to losing pitcher in two pitches, Durham told Tuley, “I’m still in shock.”

Fitting in

A week later, Durham, 23, was called up to the Cardinals and put into the starting rotation, even though he had pitched only a partial season at a level higher than Class A.

He made his big-league debut against his boyhood favorite, the Reds, at St. Louis on July 16, 1972. The first batter he faced, Pete Rose, grounded out. The next, Joe Morgan, flied out. In the second inning, Durham struck out the side. One of the victims was Tony Perez.

Durham went seven innings, allowed three runs, got little support and was the losing pitcher in a 4-1 Reds triumph. Bobby Tolan hit a solo home run _ the only homer Durham would allow in 47.2 innings for the 1972 Cardinals.

“The kid had good stuff,” Cardinals manager Red Schoendienst said to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. “He’s going to be a good pitcher. He had a good fastball and his control was good. We just didn’t get a break for him.”

Reds manager Sparky Anderson told the Dayton Daily News, “The kid had a good fastball and he kept it around the plate real well.”

According to the Post-Dispatch, Cardinals catcher Ted Simmons nicknamed Durham “The Rattlesnake” because of the way he uncoiled as he delivered a pitch. Boxscore

Tough going

On Aug. 4, 1972, when the Phillies faced the Cardinals, the starting pitchers had a combined season record of 0-11. Ken Reynolds was 0-8 and Durham was 0-3.

In the second inning, using a Bob Gibson bat, Durham got his first big-league hit, a three-run home run on a fastball down the chute from Reynolds. Then he retired the Phillies in order in the second through fifth innings and contributed two more hits, both singles. “If ever a pitcher seemed destined for victory, Durham was the guy,” the Post-Dispatch noted.

It wasn’t to be, though. The Phillies scored six runs in the eighth and won, 8-3. “Sitting forlornly in the clubhouse,” Durham was “so despondent he could hardly bring himself to talk,” the Post-Dispatch reported.

He described himself to the newspaper as “a choke artist.” Boxscore

Giant killer

After losing a fifth consecutive decision, Durham finally got his first big-league win on Aug. 18, 1972, against the Giants at Candlestick Park in San Francisco.

In addition to limiting the Giants to a run in 6.1 innings before being relieved by Diego Segui, Durham scored the Cardinals’ first two runs. Using a Ted Simmons bat, he singled and scored in the third and walloped a hanging slider from Jim Willoughby for a solo home run in the fifth.

After the game, Durham went around the clubhouse, getting autographs on a baseball from all of his teammates, the Post-Dispatch reported.

“My confidence has been restored,” Durham told the Post-Dispatch. Boxscore

Durham got one more win and again it came against the Giants. Facing a lineup with the likes of Bobby Bonds, Willie McCovey and Dave Kingman, Durham pitched a three-hitter. He also stroked two singles _ one against Juan Marichal and the other versus Sam McDowell.

“After the first inning, I zeroed in nicely on the outside zone and took the power away from their big hitters,” Durham told the San Francisco Examiner. Boxscore

End game

Durham pitched in 10 games, making eight starts, for the 1972 Cardinals and was 2-7 with a 4.34 ERA.

At some point, he experienced elbow problems and was sent back to Tulsa for the 1973 season.

On July 16, 1973, the Cardinals traded Durham to the Texas Rangers, who were managed by Whitey Herzog. The American League had the designated hitter rule, so Durham didn’t get a chance to bat. When he pitched, he wasn’t effective.

After posting a record of 0-4 with a 7.59 ERA for the 1973 Rangers, Durham, 24, was finished in the big leagues.

On July 10, 1923, Stuart started both games of a doubleheader for the Cardinals against the Braves and earned complete-game wins in both.

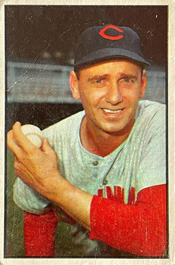

On July 10, 1923, Stuart started both games of a doubleheader for the Cardinals against the Braves and earned complete-game wins in both. A left-hander who relied on pinpoint control and an assortment of breaking pitches, Raffensberger faced the Cardinals a lot _ 79 times, including 59 starts. He lost (34 times) more than he won (23 times) versus St. Louis, but when he was good he was nearly unhittable.

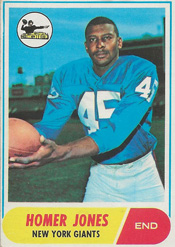

A left-hander who relied on pinpoint control and an assortment of breaking pitches, Raffensberger faced the Cardinals a lot _ 79 times, including 59 starts. He lost (34 times) more than he won (23 times) versus St. Louis, but when he was good he was nearly unhittable. A receiver with the 1960s New York Giants, Jones was a master at producing long gains. He did it either one of two ways _ hauling in deep passes, or using his deft footwork to add yardage after a grab. His career average of 22.3 yards per catch is a NFL record.

A receiver with the 1960s New York Giants, Jones was a master at producing long gains. He did it either one of two ways _ hauling in deep passes, or using his deft footwork to add yardage after a grab. His career average of 22.3 yards per catch is a NFL record. Having worn out his welcome in New York, Allen felt instantly unwelcomed in St. Louis when the Cardinals

Having worn out his welcome in New York, Allen felt instantly unwelcomed in St. Louis when the Cardinals  Soon after, when the crack turned into a chasm, the Phillies fell and the Cardinals climbed past them to win the 1964 pennant.

Soon after, when the crack turned into a chasm, the Phillies fell and the Cardinals climbed past them to win the 1964 pennant.