As Tom Murphy felt his pitching career sliding downhill, the Cardinals pulled him back into the big leagues.

On May 8, 1973, the Cardinals rescued Murphy from the Royals’ farm system, acquiring him for pitcher Al Santorini.

On May 8, 1973, the Cardinals rescued Murphy from the Royals’ farm system, acquiring him for pitcher Al Santorini.

A right-hander who had been in the Angels’ starting rotation for four years, Murphy used his season in St. Louis to show he could be effective again in the majors, After that, he transformed into a closer _ but not with the Cardinals.

Baseball cards come to life

Born in Cleveland and raised in nearby Euclid, Ohio, Tom Murphy and his identical twin brother, Roger, became college athletes. Tom was a pitcher for Ohio University and Roger became a wide receiver for Northwestern’s football team.

Tom Murphy had a combined 16-1 record his sophomore and junior seasons at Ohio U. Roger Murphy had 51 catches for Northwestern in 1966 and went on to play in the Canadian Football League.

The Astros (1965) and Giants (1966) drafted Tom Murphy but he preferred to stay in college. When the Angels drafted him in January 1967, one of the reasons he signed was they agreed to let him complete his bachelor of arts degree in English that spring, The Sporting News reported.

Murphy’s first stop in the Angels’ system was with Quad Cities, a Class A club in Iowa managed by Fred Koenig. Murphy was 5-1 with a 2.34 ERA in six starts.

The Angels called up Murphy, 22, the next year, in June 1968, and put him in the starting rotation. The Angels’ pitching coach, Bob Lemon, had been Murphy’s favorite boyhood player with the Indians, according to The Sporting News.

In beating the Yankees for his first big-league win, Murphy faced another baseball icon from his childhood, Mickey Mantle. Though Mantle, 36, was playing in his last season on wobbly knees, “I was scared,” Murphy told the Los Angeles Times. “You better believe I did a little trembling. Here was a guy I idolized.”

Murphy managed to twice retire Mantle in key situations. His strategy, he told the Times, was, “I figured I’d challenge him with my best, and let him hit it as far as he could,”

In the third inning, with runners on second and third, one out, Mantle hit “a whistling drive directly at first baseman Chuck Hinton, who threw to shortstop Jim Fregosi at second for a double play,” the Times noted.

Two innings later, Mantle batted with two on and two outs. “Murphy threw two sweeping curveballs and Mantle could do no better than hit foul balls,” the Times reported. “The third pitch was a high fastball. Mantle swung ferociously, but the ball nestled in catcher Tom Satriano’s glove” for strike three. Boxscore

Murphy made 15 starts for the 1968 Angels and had a 2.17 ERA.

California dreaming

Being a rookie in the big leagues in Southern California in 1968 made for heady times for Murphy. Tall (6 feet 3) and angular, Murphy was a bachelor who enjoyed the California beach life. Murph the Surf, they called him.

He wore the mod clothes of the time, including silk brocade Nehru jackets. As the Los Angeles Times observed when he arrived for an interview, “Murphy wears a brown shirt of Edwardian cut. It is complemented by a brown and gold ascot. The pants are hip huggers. They are white with a black stripe and bell-bottomed.”

His road roommate, pitcher Andy Messersmith, told the Times, “I get my kicks walking around with Tom and hearing what people say about his clothes. Like the day in Boston after he had just bought this gold Nehru. We walked around downtown and people thought he was Ken Harrelson (of the Red Sox). They thought he was The Hawk.”

Murphy replied, “Aw, it was because of my nose.”

In 1969, Murphy and Messersmith joined Rudy May and Jim McGlothlin _ the four M’s _ in a mod Angels starting rotation, all 25 or younger.

During spring training, players sneaked Murphy’s twin brother Roger into an Angels uniform and sent him onto the field for calisthenics. Roger lied down in the grass and used first base for a pillow, then got up and told astonished Angels manager Bill Rigney he was retiring. Rigney thought Roger was Tom until he was brought in on the gag, the Times reported.

There wasn’t much funny, though, about Tom Murphy’s season for the 1969 Angels. He had 16 losses, threw 16 wild pitches and hit 21 batters with pitches. “The statistics seem to suggest that Murphy’s pitching was as wild as his wardrobe,” John Wiebusch of the Times reported.

Murphy told the newspaper, “There are smart pitchers and stupid pitchers, and it doesn’t take a genius to classify me.

“I tend to lose my cool too quickly. Things upset me and when that happens I lose my poise.”

Murphy did much better in 1970 (16 wins) but not so well in 1971 (17 losses, but in eight of those the Angels failed to score. He also lost three games by 2-1 scores and another by 3-2.)

K.C. and the Sunshine Band

After the 1971 season, the Angels obtained a pitcher who was 29-38 with the Mets (Nolan Ryan), put him into their starting rotation and traded Murphy to the Royals in May 1972. “I can’t quite picture myself sunbathing in Kansas City,” Murphy quipped to The Sporting News.

Bob Lemon was the Royals’ manager. Murphy’s first start for him was against the Angels. He pitched well (two runs allowed in seven innings) but lost. Boxscore

In July, Murphy (3-2, 4.79 ERA) was demoted to minor-league Omaha. He pitched a no-hitter against Indianapolis and was back with the Royals in September. His highlight was a shutout against a Twins lineup with Rod Carew and Harmon Killebrew, beating Bert Blyleven. Boxscore

Murphy had an 0.34 ERA in 26.1 innings pitched for the Royals in September 1972, but when the season opened in 1973 he was back in the minors.

Join the club

The 1973 Cardinals lost 20 of their first 25 games and were looking for any help. Cardinals director of player development Fred Koenig, Murphy’s first minor-league manager, recommended him and the deal was made with the Royals.

Murphy joined a pitching staff populated with other American League castoffs such as Alan Foster, Orlando Pena and Diego Segui. His first two Cardinals appearances, both in relief, resulted in 4.1 scoreless innings, and he was moved into the starting rotation on June 10.

Though Murphy lost his first three decisions as a Cardinals starter, he pitched well. He allowed one run in a 3-1 loss to the Expos Boxscore and two runs in a 2-0 loss to the Cubs. Boxscore

His breakthrough came on July 4, 1973, with a complete-game win against the Pirates. Murphy also contributed a single and a double, scored a run and drove in another. Boxscore

He won his next start as well, beating the Dodgers in Los Angeles. Boxscore

The next day, Murphy’s twin brother pulled another prank. He got into the clubhouse, dressed in Tom’s uniform and asked trainer Gene Gieselmann for a rubdown, saying he’d hurt his arm in a surfing accident. Gieselmann went to work, thinking it was Tom.

Murphy also became a source of amusement for Bob Gibson, who delighted in imitating his teammate’s herky-jerky pitching motion. “Murphy has the habit of prefacing his windup by flipping his gloved hand forward, as if shooing flies,” the St. Louis Post-Dispatch noted.

On July 29, 1973, Murphy had two hits in the Cardinals’ win against the Cubs but didn’t qualify for a decision. Boxscore In his next start, he limited the Expos to two runs. but was the losing pitcher. Balor Moore shut out the Cardinals on four hits. Boxscore

Soon after that, Murphy was moved to the bullpen and was effective. He finished the season 3-7 with a 3.76 ERA. In his six relief appearances totaling 13.1 innings, he was 1-0 with an 0.68 ERA.

Finding a niche

Murphy’s strong relief work for the Cardinals was a sign of good things to come for him. It was the Brewers, though, who benefitted.

On Dec. 8, 1973, the Cardinals sent Murphy to the Brewers for utilityman Bob Heise. Brewers manager Del Crandall made Murphy, 28, the closer. “He’s got heart,” Crandall told The Sporting News. “While other guys get nervous in certain situations, he can go out there and do the job.”

Using a combination of sinkers and sliders, Murphy made 70 relief appearances for the 1974 Brewers and was 10-10 with 20 saves and a 1.90 ERA.

He had 20 saves again for the Brewers the next year but overall wasn’t as dominant, posting a 1-9 record and 4.60 ERA.

Murphy went on to finish his playing career with the Blue Jays. In 12 seasons in the majors, he was 68-101 with 59 saves and a 3.78 ERA.

What Donovan needed more than the luck of the Irish was a dugout full of run producers and premium pitchers.

What Donovan needed more than the luck of the Irish was a dugout full of run producers and premium pitchers.

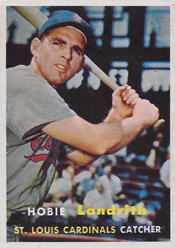

At 5-foot-8, according to the Associated Press and his Topps baseball card, Landrith stood “about as tall as the bat boy,” the Baltimore Sun noted, but he played in the majors for 14 seasons, including two with the Cardinals.

At 5-foot-8, according to the Associated Press and his Topps baseball card, Landrith stood “about as tall as the bat boy,” the Baltimore Sun noted, but he played in the majors for 14 seasons, including two with the Cardinals. In 1973, the Cardinals threw a lifeline to Foster, inviting him to spring training as a non-roster pitcher. He made the most of the opportunity, earning a spot on the Opening Day pitching staff and working his way into the starting rotation.

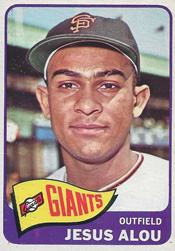

In 1973, the Cardinals threw a lifeline to Foster, inviting him to spring training as a non-roster pitcher. He made the most of the opportunity, earning a spot on the Opening Day pitching staff and working his way into the starting rotation. A perfect throw by Alou in a game against the Cardinals nailed Uecker at the plate, aiding a win for the Giants that moved them into sole possession of first place in the 1964 National League pennant race.

A perfect throw by Alou in a game against the Cardinals nailed Uecker at the plate, aiding a win for the Giants that moved them into sole possession of first place in the 1964 National League pennant race.