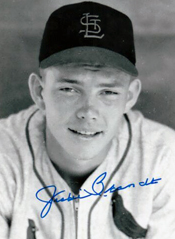

Jackie Brandt was an outfielder who earned a National League Gold Glove Award and was named to the American League all-star team, but people wanted more from him.

He was supposed to be the next Mickey Mantle, but he wasn’t.

He was supposed to be a sure bet to receive the National League Rookie of the Year Award with the Cardinals, but he didn’t.

He was supposed to be a flake, but maybe was just good at pretending to be one.

Quick rise

Brandt was an accomplished amateur pitcher and outfielder in his hometown of Omaha, but he didn’t get any offers to turn pro. Three months after he graduated from high school in 1952, he was wielding a sledgehammer as a boilermaker’s helper for the Union Pacific Railroad when Bob Hall, president of the minor-league club in Omaha, contacted the Cardinals and recommended Brandt to them, The Sporting News reported.

Cardinals scout Runt Marr went to Omaha, saw him throw and offered a contract, Brandt recalled to The Sporting News. A right-handed batter, Brandt preferred playing the outfield instead of pitching, and the Cardinals went along with his request, he told the Associated Press.

In his first regular-season game as a pro for Ardmore (Okla.) in the Class D Sooner State League, Brandt tore ligaments in his right leg and was sidelined for a month. When he came back, he tore up the league, hitting .357 with 131 RBI in 120 games.

Brandt made an impressive climb through the Cardinals’ system, hitting .313 for manager George Kissell’s Class A Columbus (Ga.) team in 1954 and .305 for Class AAA Rochester in 1955.

His performance for Rochester marked Brandt, 21, as a prime prospect for the majors. He excelled as a hitter (38 doubles, 12 triples), fielder (20 assists, 420 putouts) and base runner (24 steals). “Brandt is one of the best-looking kids I’ve ever seen,” Rochester manager Dixie Walker told the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle. “He’ll be a major league star.”

Cardinals general manager Frank Lane said his Reds counterpart, Gabe Paul, offered $100,000 for Brandt. In rejecting the proposal, Lane told The Sporting News, “If Gabe offers $100,000 for him, the kid is worth every bit of $400,000.”

After Cardinals manager Fred Hutchinson saw Brandt play winter ball in Havana following the 1955 minor-league season, he said to The Sporting News, “He has a physical makeup similar to Mickey Mantle. He’s got the same kind of sloping shoulders, strength and speed. He showed exceptional aptitude defensively, a great knack of getting a jump on the ball and a strong arm.”

When New York Times columnist Arthur Daley got his first look at Brandt during spring training in 1956, he observed that the rookie had the “cat-like gait of Mickey Mantle. In fact, he looks as if he might be Mickey’s little brother.”

Another New York columnist, Red Smith, described Brandt as “a smaller, slighter version of Mickey Mantle.”

Great expectations

Brandt’s spring training performance earned him a spot on the Cardinals’ 1956 Opening Day roster and heightened expectations. Cardinals outfielders had won the National League Rookie of the Year Award in 1954 (Wally Moon) and 1955 (Bill Virdon), so Brandt was being touted as a favorite to get the honor in 1956.

“He is faster than either Moon or Virdon, both on the bases and in the outfield,” The Sporting News reported. “He loves to run, loves to hit and he doesn’t know the meaning of pressure.”

Brandt “could be another Terry Moore,” Cardinals chief scout Joe Mathes said to the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, referring to the center fielder on the club’s 1940s championship teams.

Unfazed, Brandt told The Sporting News he could hit as well as any Cardinals player “except Stan” Musial. “Confidence is my major asset,” Brandt said.

Hutchinson, though, preferred a lineup with experienced big-leaguers. The Cardinals opened the 1956 season with Hank Sauer in left field, Virdon in center, Musial in right, Moon at first base and Brandt on the bench. In May, they dealt Virdon to the Pirates for Bobby Del Greco and made him the center fielder.

When Del Greco got injured, Brandt filled in and came through with consecutive three-hit games. Boxscore and Boxscore

Future shock

After a few starts in late May, Brandt was back on the bench. Dissatisfied with sitting and watching, he asked the Cardinals to send him to the minors so he could play every day, he told author Steve Bitker in the book “The Original San Francisco Giants.”

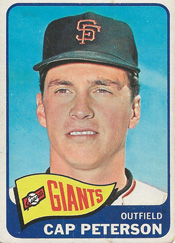

Instead, the Cardinals traded him. He was part of the June 1956 deal that sent second baseman Red Schoendienst to the Giants for shortstop Al Dark and others. The Giants insisted on Brandt being included. “We wouldn’t have made the deal without him,” Giants general manager Chub Feeney told United Press. “Frankly, we were surprised that the Cards would let him go.”

Brandt batted .286 with one home run in 42 at-bats for the Cardinals and fielded flawlessly. (According to researcher Tom Orf, Brandt is one of two players who began his career with the Cardinals, hit one home run for them and went on to slug 50 or more in the majors. The other is Randy Arozarena.)

On the day the trade was made, the Cardinals were 29-23 and one game out of first place in the National League. Frank Lane thought having Dark as their shortstop could spark them to a pennant. “Brandt could come back to haunt us, but we’re concerned about 1956 and not the future,” Lane explained to The Sporting News.

J. Roy Stockton of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch countered: “We don’t consider the Cardinals a sufficient threat in 1956 to justify trading away Brandt.”

(The Cardinals hit the skids in July and finished 76-78, 17 games behind the champion Dodgers.)

Schoendienst told the Post-Dispatch, “Lane didn’t hurt the Cardinals trading me. It was his dealing off young players like Bill Virdon and Jackie Brandt … Brandt alone, counting what he can do now and what he’ll do in the future, is worth all four players the Cardinals got in the Giants deal.”

Golden gate

The Giants made Brandt their left fielder and he hit .299 with 11 home runs for them in 1956.

After spending most of the next two seasons in military service, Brandt was the Giants’ left fielder when they opened the 1959 season at St. Louis against the Cardinals. In the ninth inning, with a runner on first, one out and the score tied at 5-5, Brandt made two unsuccessful sacrifice bunt attempts, then ripped a Jim Brosnan pitch 400 feet to left-center for a double, driving in the winning run. Boxscore

Brandt went on to hit .270 for the 1959 Giants and ranked first among National League left fielders in fielding percentage (.989), earning him a Gold Glove Award. The other NL Gold Glove outfielders that season were teammate Willie Mays (center) and the Braves’ Hank Aaron (right).

(According to the authorized biography “Willie Mays: The Life, The Legend,” there were tensions between Brandt and Mays. “Brandt was outspoken and he was always criticizing Mays,” Giants broadcaster Lon Simmons said.)

Brandt was traded to the Orioles after his Gold Glove season.

Offbeat Oriole

Brandt played six seasons (1960-65) for the Orioles and was their center fielder for most of that time. In 1961, when he hit .297 and scored 93 runs, Brandt was named to the American League all-star team, but it was during his Orioles days that he got labeled a flake.

Teammate Boog Powell told the Baltimore Sun, “He had a pair of alligator shoes and, at a team party, decided to take them for a swim. He just walked into the pool, then out, and continued the evening like nothing had happened.”

(Decades later, when Powell operated a barbecue stand at Camden Yards in Baltimore, Brandt tapped him on the shoulder, said, “Pardon me, sir, but can you spare a poor man a sandwich?” and then kissed his old teammate square on the lips, the Sun reported.)

In a spring training game, Brandt got caught in a rundown and did a backflip to avoid the tag, the Sun reported. Another time, Brandt scored ahead of Jim Gentile, who missed the plate with his slide. Brandt bent down, picked up Gentile’s foot and placed it neatly on the plate, according to the Philadelphia Daily News.

Brandt’s words could be as amusing as his actions.

According to Milton Gross of the North American Newspaper Alliance, after the 1964 season, when Brandt hit less than .250 for the second straight year, Orioles general manager Lee MacPhail wished him a good winter. Brandt replied, “I always have a good winter. The bad summers are what troubles me.”

Regarding his inability to measure up to Mickey Mantle, Brandt told Gross, “I do everything pretty fair, but I’m not up to my potential. Maybe I’m living in the future.”

Orioles manager Hank Bauer said to the Sun, “I asked him how he managed to misplay a fly. He said, ‘I lost in the jet stream.’ “

According to the Baltimore newspaper, other gems uttered by Brandt included:

_ “This year, I’m going to play with harder nonchalance.”

_ “It’s hard to tell how you’re playing when you can’t see yourself.”

Brandt told author Steve Bitker, “My mind works crazy. I don’t do anything canned. Whatever comes to mind, I say or do.”

At least one popular story told about Brandt turned out to be untrue. As reported by the Associated Press and the Newspaper Enterprise Association, Brandt, wanting to experience some of the 40 flavors offered at an ice cream place, drove 30 miles out of his way to get there _ and then ordered vanilla. In 1983, the Baltimore Sun reported it was Ed Brandt, a reporter who covered the Orioles for the newspaper, who drove the extra miles for the ice cream and settled for vanilla. Over time, Jackie, not Ed, got associated with the tale.

“I’m shrewder than most of the guys think,” Brandt, the player, said to North American Newspaper Alliance.

Being a pro

When the Phillies swapped Jack Baldschun to the Orioles for Brandt in December 1965, Larry Merchant of the Philadelphia Daily News called it a trade of “a screwballing relief pitcher for a screwball of an outfielder.”

Regarding his reputation for being a flake, Brandt told Merchant, “We’re paid to entertain. It’s like being on stage. People want a show. They pay three bucks, so they ought to get one.”

The 1966 Phillies were a haven for free spirits, with Bo Belinsky, Phil Linz and Bob Uecker joining Brandt on the roster. Brandt didn’t play regularly, but was serious about finding ways to contribute.

“For weeks at a stretch, he would pitch batting practice 25 minutes a day,” Bill Conlin reported in the Philadelphia Daily News. “He would catch batting practice and became Jim Bunning’s preferred warmup catcher because of his knack of setting a low target with his glove.”

The Phillies sent Brandt to the Astros in June 1967 and he completed his final season in the majors with them. In his last big-league appearance, on Sept. 2, 1967, at St. Louis, Brandt singled versus Steve Carlton. Boxscore

In 11 seasons in the majors, Brandt produced 1,020 hits, including 112 home runs.

In the ninth inning, with the score tied at 5-5, reliever Don Larsen, the former Yankee who pitched a World Series perfect game, walked Cardinals leadoff batter Curt Flood.

In the ninth inning, with the score tied at 5-5, reliever Don Larsen, the former Yankee who pitched a World Series perfect game, walked Cardinals leadoff batter Curt Flood.

On May 8, 1973, the Cardinals rescued Murphy from the Royals’ farm system, acquiring him for pitcher

On May 8, 1973, the Cardinals rescued Murphy from the Royals’ farm system, acquiring him for pitcher  What Donovan needed more than the luck of the Irish was a dugout full of run producers and premium pitchers.

What Donovan needed more than the luck of the Irish was a dugout full of run producers and premium pitchers.

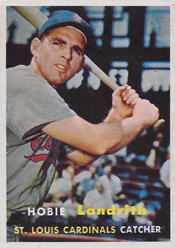

At 5-foot-8, according to the Associated Press and his Topps baseball card, Landrith stood “about as tall as the bat boy,” the Baltimore Sun noted, but he played in the majors for 14 seasons, including two with the Cardinals.

At 5-foot-8, according to the Associated Press and his Topps baseball card, Landrith stood “about as tall as the bat boy,” the Baltimore Sun noted, but he played in the majors for 14 seasons, including two with the Cardinals.