About the same time that fans of Milwaukee baseball learned the Braves planned to abandon them, the club’s most prominent pitcher, Warren Spahn, got cast aside, too.

So, when Spahn returned to Milwaukee for the first time as a member of the Mets, the fans there came out to cheer for him and against the Braves.

So, when Spahn returned to Milwaukee for the first time as a member of the Mets, the fans there came out to cheer for him and against the Braves.

The drama didn’t end there. Spahn was matched that night against his protege and former road roommate, Wade Blasingame. Both were destined to wind up with a Cardinals farm team.

Mr. Brave

A left-hander who developed into a consistently big winner, Spahn began his major-league career with the 1942 Boston Braves (managed by Casey Stengel), served in combat during World War II, and moved with the club to Milwaukee in 1953. He was revered in Milwaukee for being the staff ace and for helping the Braves win two National League pennants (1957 and 1958) and a World Series title (1957).

“No individual made a greater contribution to the fabulous Milwaukee baseball story,” The Sporting News reported on Spahn. “He was truly Mr. Brave.”

Spahn won 20 or more 13 times, including six years in a row (1956-61). He was 42 when he won 23 for the 1963 Braves.

Trouble developed for both Spahn and the Milwaukee fan base in 1964. Spahn quit winning, and was shifted to the bullpen against his wishes by manager Bobby Bragan. Spahn finished the season at 6-13 with a 5.29 ERA.

“He was dead on his feet,” Bragan told The Sporting News. “His legs were gone. He couldn’t get off the mound, and they were bunting him silly.

“If any other pitcher had been shelled the way he was,” Bragan said, “he would have been shipped to (minor-league) Denver.”

The Braves wanted Spahn to stop pitching and offered him several jobs in the organization, including a radio broadcasting gig, The Sporting News reported. Spahn wanted to play instead.

Then the Braves delivered a double salvo of damaging decisions to the fans of Milwaukee baseball:

_ In October 1964, the Braves’ board of directors voted to approve a move of the franchise to Atlanta. The Braves were ready to go, but the National League ordered them to play one more season in Milwaukee in 1965, putting them in a lame-duck position with a furious fan base.

_ A month later, the Braves sold Spahn’s contract to the Mets, a move the scorned fans viewed as thankless.

“They got rid of me because of the money, my salary,” Spahn told The Sporting News. According to the New York Daily News, Spahn was paid $85,000 in 1964.

Double duty

The Mets’ manager, Casey Stengel, gave him the dual role of pitcher and pitching coach. “Pitching is first, then coaching,” Spahn told The Sporting News. He said to Dick Young of the Daily News, “I think I’m still a 20-game winner.”

Whitey Ford, who attempted to be both pitcher and pitching coach for manager Yogi Berra’s 1964 Yankees and found it daunting, delivered a message to Spahn through The Sporting News: “You’ll be sorry.”

(Berra, who was fired by the Yankees after the club was defeated by the Cardinals in the 1964 World Series, joined Spahn as a coach on Stengel’s 1965 Mets staff. Berra played in four May games for the 1965 Mets, then stuck solely to coaching.)

Spahn, 44, won his first two decisions with the 1965 Mets. Both were complete games _ one against the Dodgers Boxscore and the other versus the Giants. Boxscore

(In his first start versus the Cardinals as a Met, Spahn was matched against Bob Gibson. Lou Brock hit a two-run home run and the Cardinals won, 4-3. Boxscore and radio broadcast)

Out for revenge

Spahn was 3-3 with a 3.51 ERA heading into his return to Milwaukee to oppose the Braves. The fans there were showing their contempt about the impending move to Atlanta by staying away from County Stadium.

After a paid crowd of 33,874 attended the 1965 home opener, subsequent April and May Braves home games drew an average paid attendance of 3,000. Paid attendance figures for the Cardinals’ three-game series at Milwaukee April 27-29 were 1,677, 1,324 and 2,182.

The turnout for the Thursday night game with the Mets on May 20, 1965, was a lot bigger _ 19,140 total (17,433 at full price, 1,707 youngsters admitted for 50 cents each) _ and most were there to pay tribute to Spahn.

“They made no secret of the fact they were rooting not for the Braves but for Spahn,” The Sporting News reported. “They cheered when his name was announced, when he took the mound and when he threw so much as a strike. They gave him a standing ovation when he went to bat.”

Dick Young of the Daily News observed, “He was to be their instrument of revenge. They came just for him, hoping, praying, he would beat the Braves.”

Several brought homemade banners and placards, including one with the message, “Down the Lousy Saboteurs. C’mon, Spahn, Mow Down the Betrayers,” the Daily News reported.

The Braves’ lineup that night featured Hank Aaron, Eddie Mathews, Joe Torre, Felipe Alou and 21-year-old starting pitcher Wade Blasingame. A left-hander, Blasingame got called up to the Braves in June 1964 and roomed on the road with Spahn, who became a mentor. Blasingame was 9-5 (including a shutout of the pennant-bound Cardinals Boxscore) for the 1964 Braves.

“There is a growing feeling (Blasingame) is about to become the new Spahn,” The Sporting News reported.

Spahn “taught me more in a year than I ever knew before,” Blasingame told United Press International.

All business

Blasingame and Spahn waged a scoreless duel for four innings. Then, in the fifth, Spahn became unglued. The Braves scored twice, then loaded the bases for Eddie Mathews, the left-handed slugger who was, according to George Vecsey of Newsday, “one of Spahn’s closest friends.”

When the count got to 1-and-1, “I couldn’t afford to get behind,” Spahn explained to United Press International. “He had been looking bad on the slider all night, but I second-guessed myself and threw him a fastball. Trouble was, I was indecisive about whether to throw it down and in, or down and away. So I came right over the plate.”

Mathews clobbered it _ “a mile past the bleachers in right,” the Daily News reported _ for a grand slam, giving the Braves a 6-0 lead.

“Spahn kicked the top of the mound to dust, and picked up the resin bag and slammed it down,” Dick Young noted.

Mathews said to Newsday, “If I felt something special about hitting a home run against Spahn, I’d tell you. I didn’t. He’s just another pitcher.”

In his book, “Eddie Mathews and the National Pastime,” Mathews said, “Spahnie and I went out and drank together after the ballgame, but there was no sentiment while he was on the mound.”

Hank Aaron followed with a single, stole second and eventually scored on Rico Carty’s second double of the inning, capping the seven-run outburst.

Spahn completed the inning, then was lifted for a pinch-hitter.

Blasingame held the Mets hitless until the seventh when, with two outs, Ron Swoboda singled, scoring Billy Cowan, who had walked and moved to second on a wild pitch.

Blasingame, who finished with a one-hitter, told George Vecsey he felt bad for Spahn: “I know he wanted to beat us very much _ maybe more than I wanted to beat them.” Boxscore

Tulsa time

Four days after his loss at Milwaukee, Spahn pitched a complete game, beating Jim Bunning and the Phillies. Boxscore Then he lost eight in a row, and the Mets placed him on waivers. In 20 games with the Mets, Spahn was 4-12.

The Giants claimed him and he finished the 1965 season, his last, with them, going 3-4. Spahn’s 363 career wins are the most by a left-handed pitcher.

“I never did retire from pitching,” Spahn told writer Roger Kahn. “It was baseball that retired me.”

Wade Blasingame was 16-10 for the 1965 Braves, but never achieved another double-digit win season. In 10 years with the Braves, Astros and Yankees, he was 46-51.

(Blasingame and Jim Bouton were Astros teammates in 1969. In his book, “Ball Four,” Bouton wrote, “Today, Blasingame was wearing a blue bellbottom suit, blue shirt, a blue scarf at his throat and was smoking a long thin cigar, brown. Teammate Fred Gladding said, ‘Little boy blue, come blow my horn.’ Everybody on the bus went ‘Oooooh.’ Blasingame feigned indifference.”)

In 1967, Cardinals general manager Stan Musial hired Spahn to be manager of the Tulsa farm club. Spahn held the job for five years, but was gone by March 1973, when the Cardinals acquired Blasingame from the Yankees and assigned him to Tulsa.

Blasingame was 1-0 with an 0.90 ERA in two months with Tulsa before being traded to the Cubs’ Wichita farm team for another left-hander, Dan McGinn.

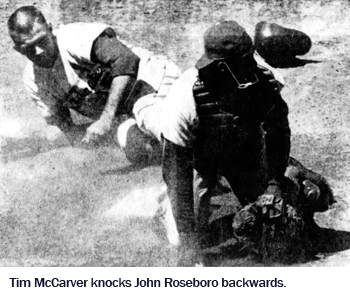

As a standout high school athlete in Memphis, McCarver

As a standout high school athlete in Memphis, McCarver  On Nov. 20, 1983, Coryell brought the San Diego Chargers to Busch Stadium to play the Cardinals.

On Nov. 20, 1983, Coryell brought the San Diego Chargers to Busch Stadium to play the Cardinals. When he was elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame on Feb. 9, 2023, Coryell correctly was hailed as an innovator whose offenses with the Cardinals, and later the San Diego Chargers, were thrilling to watch and nerve-wracking to defend.

When he was elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame on Feb. 9, 2023, Coryell correctly was hailed as an innovator whose offenses with the Cardinals, and later the San Diego Chargers, were thrilling to watch and nerve-wracking to defend. On Feb. 8, 1933, the Cardinals acquired pitcher Dazzy Vance and shortstop Gordon Slade from the Dodgers for pitcher Ownie Carroll and infielder Jake Flowers.

On Feb. 8, 1933, the Cardinals acquired pitcher Dazzy Vance and shortstop Gordon Slade from the Dodgers for pitcher Ownie Carroll and infielder Jake Flowers.