If the career of Nate Colbert had gone according to script, he would have been the power-hitting first baseman the Cardinals needed in the early 1970s.

Unfortunately for the Cardinals, the Astros fouled up the plan and the Padres benefitted.

Unfortunately for the Cardinals, the Astros fouled up the plan and the Padres benefitted.

A right-handed slugger with power to all fields, Colbert played 10 years in the big leagues and clubbed 22 or more home runs in five consecutive seasons. He remains the Padres’ career leader in home runs with 163, two more than Adrian Gonzalez hit for San Diego.

Happy at home

Born and raised in St. Louis, Colbert was a Cardinals fan who attended games at Busch Stadium, formerly Sportsman’s Park.

“I lived close to old Busch Stadium,” Colbert said years later to the Los Angeles Times, “and I sat in the bleachers with a glove, trying to catch batting practice home runs.”

On May 2, 1954, Colbert, 8, was supposed to play in a youth baseball game, but skipped it to attend a Sunday doubleheader between the Giants and Cardinals. “I almost never missed a Sunday doubleheader when the Cardinals were at home,” Colbert recalled to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

That day, Colbert got to see Stan Musial become the first big-league player to slug five home runs in a doubleheader.

“Stan was my idol after that day,” Colbert said to the Los Angeles Times.

According to the Los Angeles newspaper, Colbert had a congenital defect in his spine that created a constant muscle spasm, but he developed into a standout baseball player, first with the Mathews-Dickey Boys Club team in the Khoury League and then at Sumner High School in St. Louis.

Also, while in high school, Colbert helped out in the Cardinals’ clubhouse, “and sometimes they let me take batting practice,” Colbert told Bob Wolf of the Los Angeles Times. “Before games, I would sit in Stan’s locker, and he was great to me. He was always so kind.”

Cardinals scout Joe Monahan said to the Post-Dispatch, “He was a good-looking hitter. He had fine wrists and was already capable of overpowering the ball.”

As a high school senior, Colbert got a formal tryout with the Cardinals at their ballpark. With manager Johnny Keane watching, Colbert hit two balls against the scoreboard in left and another into the screen in right. The Cardinals signed him three days after he graduated in June 1964.

Major leap

After a summer with a Cardinals rookie league team in Florida, a broken hand limited Colbert to 81 games with Class A Cedar Rapids in 1965 and he was left off the Cardinals’ winter roster. “I guess they figured no one would take a risk on a 19-year-old kid with a broken hand in Class A ball,” Colbert told the Post-Dispatch.

The Astros, though, were in a mood to gamble, and they selected Colbert in the November 1965 draft of unprotected players.

Baseball rules required the Astros to keep Colbert in the majors all of the 1966 season or offer him back to the Cardinals.

“The Astros knew Colbert wasn’t ready for the major leagues,” The Sporting News noted, “but they liked his potential and decided to make the sacrifice of keeping a youngster on the bench who wouldn’t be able to help them much.”

Though he was in the big leagues with the likes of 1966 Astros teammates Joe Morgan, Rusty Staub and Jim Wynn, “I hated to leave St. Louis,” Colbert later told the Los Angeles Times. “It took me until my mid-20s not to root for the Cardinals. Whenever I saw their uniform, I wished I was in it.”

Colbert appeared in 19 games, 12 as a pinch-runner, with the 1966 Astros and was hitless in seven at-bats. After spending most of the next two seasons in the minors, he was picked by the Padres in the National League expansion draft.

Pride of the Padres

Bill Davis was the Opening Day first baseman for the 1969 Padres, but he struggled to hit early in the season. Colbert got a chance and made the most of it, hitting home runs in three consecutive games for the Padres from April 24-26 and earning the first base job.

When the Padres went to St. Louis for the first time in May 1969, Colbert had six hits in 12 at-bats during the three-game series. One of those hits was a two-run home run versus former Astros teammate Dave Giusti. Padres manager Preston Gomez credited hitting coach and ex-Cardinal Wally Moon with helping Colbert develop a more compact swing without losing power, the Post-Dispatch reported. Boxscore

For the 1969 season, his first as a big-league regular, Colbert hit .293 in 12 games against the Cardinals with an on-base percentage of .370.

Colbert went on to have seasons of 38 home runs in 1970, 27 in 1971 and 38 again in 1972. Contrast that with the home run totals of the primary Cardinals first basemen of that time: Joe Hague (14 in 1970 and 16 in 1971) and Matty Alou (three in 1972).

Before acquiring slugger Dick Allen from the Cardinals in October 1970, the Dodgers asked the Padres whether Colbert was available, Ross Newhan of the Los Angeles Times reported. “If we traded him now,” Preston Gomez responded, “we’d have to leave town.”

Colbert “may be baseball’s best young slugger,” the Times declared in April 1971.

Launching pad

Colbert did some of his best slugging against pitchers such as Don Sutton (seven home runs), Tom Seaver (five) and Phil Niekro (four). “He hits all of us good, but me he wears out,” Seaver told United Press International in July 1972.

A month later, on Aug. 1, 1972, Colbert had his biggest day, hitting five home runs in a doubleheader against the Braves in Atlanta and joining his boyhood hero, Stan Musial, as the only big-leaguers to achieve the feat.

In the first game that Tuesday night, Colbert hit a three-run homer versus Ron Schueler in the first inning and a solo shot against Mike McQueen in the seventh. He also had two singles, including one that drove in a run, and totaled five RBI. Boxscore

In the second game, Colbert slammed home runs against Pat Jarvis (grand slam in second), Jim Hardin (two-run shot in seventh) and Cecil Upshaw (two-run shot in ninth) and totaled eight RBI. For the doubleheader, Colbert produced 13 RBI and 22 total bases. Boxscore

Not only did he hit each home run against a different pitcher, he took just six swings to accomplish the feat. Colbert hit the grand slam on a 1-and-0 offering; the other four homers came on first-pitch swings, the Los Angeles Times reported. “Every pitch was either high in the strike zone or right down the middle,” Colbert told the newspaper.

Hank Aaron played first base for the Braves in both games that evening and after Colbert’s fifth home run, “He stopped me as I went out to first base,” Colbert told the Los Angeles Times. “He said, ‘That’s the greatest thing I’ve ever seen.’ “

According to the Times, Colbert came within inches of hitting two more home runs that evening. Both of his singles came after fly balls that barely curved foul.

“Nate is just starting to mature as a hitter,” Hank Aaron said to the Post-Dispatch. “The five home runs he hit against us went to all fields and none of them was cheap. He didn’t even swing hard. That’s how strong he is.”

Reds manager Sparky Anderson told the St. Louis newspaper, “I used to think Lee May was the strongest hitter in the league, but now I think Colbert is.”

Stan the Man

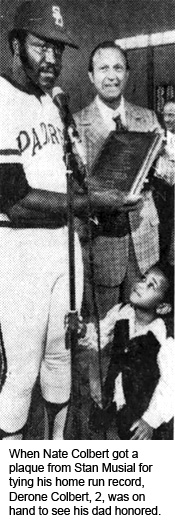

Two weeks later, on Aug. 16, 1972, when the Cardinals were in San Diego, Colbert was honored for his five-homer feat in a ceremony before the game. Stan Musial was on hand to congratulate him.

According to the Associated Press, in presenting a plaque to Colbert, Musial said to him, “Baseball is a game of records and they’re meant to be tied or broken. I’m happy one of mine was tied by a St. Louis boy and a former Cardinal.”

Musial then added, “We made a mistake when we let you go.”

In the game that followed, Colbert hit a home run against Bob Gibson, but the Cardinals won. (For his career, Colbert batted .239 with two home runs, 11 hits and 11 walks versus Gibson). Boxscore

Years later, the Los Angeles Times reported, “Musial and Colbert have a common bond that has made them good friends.”

Colbert said to the newspaper in 1989, “Now when I see him, he says, ‘We’re the only ones to do it.’ “

Trials and tribulations

Chronic back pain shortened Colbert’s playing career. “My back got worse and worse,” he told the Los Angeles Times. “It was deterioration of the vertebrae.”

In a three-way trade involving the Cardinals, Colbert was sent to the Tigers in November 1974. The next year he was shipped to the Expos and he ended his playing career with the 1976 Athletics.

Colbert hit 173 career home runs and had more strikeouts (902) than hits (833). “Considering my medical history, I probably shouldn’t even have played major league baseball,” he told the Los Angeles Times.

After his playing days, Colbert worked for the Padres as a minor-league coach and instructor, and in community relations, until October 1990 when he was indicted on 12 felony counts involving fraudulent loan applications.

Colbert was sentenced to a year in federal custody after he pleaded guilty to a federal bank fraud charge as part of a plea bargain arrangement, said assistant U.S. attorney William Hayes.

On Jan. 18, 1973, Cepeda, 35, became the first big-league player acquired to be a designated hitter. The Red Sox signed him one week after club owners voted to allow the American League to use a designated hitter on an experimental basis for the next three seasons.

On Jan. 18, 1973, Cepeda, 35, became the first big-league player acquired to be a designated hitter. The Red Sox signed him one week after club owners voted to allow the American League to use a designated hitter on an experimental basis for the next three seasons. Standing 5 feet 9, he swung a 32-ounce stick _ “Dick Allen cleans his teeth with bats like that,” Doyle told Stan Hochman of the Philadelphia Daily News _ but he clobbered the Cardinals and, most improbably, their ace, Bob Gibson.

Standing 5 feet 9, he swung a 32-ounce stick _ “Dick Allen cleans his teeth with bats like that,” Doyle told Stan Hochman of the Philadelphia Daily News _ but he clobbered the Cardinals and, most improbably, their ace, Bob Gibson. A 6-foot-7 power forward and relentless rebounder, Silas debuted in the NBA with the St. Louis Hawks in 1964. His first regular-season appearance with them came two days after Gibson pitched the Cardinals to victory in Game 7 of the 1964 World Series.

A 6-foot-7 power forward and relentless rebounder, Silas debuted in the NBA with the St. Louis Hawks in 1964. His first regular-season appearance with them came two days after Gibson pitched the Cardinals to victory in Game 7 of the 1964 World Series. On Dec. 17, 1932, the Cardinals traded their future Hall of Fame first baseman, Jim Bottomley, to the Reds for pitcher Ownie Carroll and outfielder Estel Crabtree.

On Dec. 17, 1932, the Cardinals traded their future Hall of Fame first baseman, Jim Bottomley, to the Reds for pitcher Ownie Carroll and outfielder Estel Crabtree.