Rogers Hornsby slammed the door on the Cardinals but it didn’t shut.

On Oct. 25, 1932, the Cardinals signed Hornsby for a second stint with them.

On Oct. 25, 1932, the Cardinals signed Hornsby for a second stint with them.

The reunion seemed unimaginable six years earlier when Hornsby and Cardinals owner Sam Breadon quarreled during contract talks. Reaching a boiling point, Hornsby stormed out of Breadon’s office, slamming the door behind him and triggering his banishment from the club.

Hit and miss

In December 1926, Hornsby was at the height of his popularity in St. Louis. A second baseman and right-handed batter of exceptional skill, he hit better than .400 three times with the Cardinals and earned six of his seven National League batting titles with them. In May 1925, Hornsby became Cardinals player-manager, replacing Branch Rickey, who moved into the front office. Hornsby led them to their first World Series title the following year.

The relationship between Hornsby and Breadon became strained during the 1926 championship season. As the St. Louis Star-Times noted, Breadon grew uneasy with the amount of gambling Hornsby was doing on horse races. According to author Mike Mitchell in his book “Mr. Rickey’s Redbirds,” Hornsby often was visited at the ballpark by a bookmaker, Frank Moore.

For his part, Hornsby was miffed that Breadon scheduled exhibition games for the Cardinals during the pennant stretch. Hornsby also resented Rickey’s authority in player personnel decisions and clashed with him, upsetting Breadon.

Shortly before Christmas Day 1926, Hornsby and Breadon met to discuss a contract, but neither was feeling the holiday spirit.

According to the Star-Times, Breadon offered a one-year deal for $50,000. Hornsby demanded three years at $150,000. Wanting control of all player personnel decisions, Hornsby also insisted that Breadon fire Rickey.

The talks deteriorated further when Breadon introduced a contract clause banning Hornsby from attending a horse race or from betting on one, and prohibiting him from associating with bookmakers, author Mike Mitchell noted.

The meeting unraveled and so did Hornsby, who exited in a huff. Fed up, Breadon called the Giants and agreed to trade Hornsby to them for second baseman Frankie Frisch and pitcher Jimmy Ring.

Hornsby played in 1927 with the Giants (filling in as manager in September when John McGraw became ill) and in 1928 with the Braves (taking over as manager in May) before going to the Cubs. Near the end of the 1930 season, he became player-manager of the Cubs.

Cubs capers

Hornsby had the support and admiration of Cubs owner William Wrigley Jr., who, according to the Chicago Tribune, called Hornsby “the smartest manager and the smartest player I have ever seen.”

When William Wrigley Jr. died in January 1932, his son, Philip Wrigley, took over and relied on the experience of club president William Veeck Sr. Without William Wrigley Jr., to protect him, Hornsby and Veeck Sr. clashed. “The temperature between them had dropped to freezing,” The Sporting News reported.

In addition, Hornsby’s relations with some Cubs players became strained. He “snarled at the athletes and injured the tender feelings of quite a few,” The Sporting News noted.

In his autobiography, “My War With Baseball,” Hornsby said Veeck Sr. “tried to make some of my managing decisions from his office and it was obvious we didn’t see eye to eye.”

On the night of Aug. 2, 1932, with the Cubs in second place at 53-46, five behind the Pirates, Veeck Sr. fired Hornsby and replaced him with Charlie Grimm.

A subsequent investigation by baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis disclosed that Hornsby had borrowed about $6,000 from four Cubs players to cover his horse racing bets, the Star-Times reported.

The Cubs went on to overtake the Pirates and win the National League pennant. When Cubs players met to determine how to divide their share of the World Series proceeds, they voted to give Hornsby nothing.

Forgive us our trespasses

After winning National League pennants in 1930 and 1931, the Cardinals finished 72-82 in 1932, 18 behind the champion Cubs. The Cardinals ranked sixth in the eight-team league in both hits and runs scored.

Seeking a hitter, Breadon and Rickey turned to Hornsby, who was at his St. Louis County farm. According to Red Smith of the Star-Times, Hornsby “had been an apparent outcast from baseball, passed up by every major-league club except the Cardinals, and his farm property is under federal attachment for unpaid income taxes and penalties.”

The Cardinals signed Hornsby to a one-year contract for $15,000. The deal included a provision “that at the close of the 1933 season he will be given his unconditional release and therefore will be free to sell his services to the highest bidder,” the Star-Times reported.

In essence, Hornsby had a contract that would grant him free agency. Ever the gambler, he was betting on himself that he would parlay a productive 1933 season into a more lucrative offer the following year.

Another unusual twist: With second basemen Frankie Frisch and Rogers Hornsby, the Cardinals had the players who were swapped for one another six years earlier.

Considering the genuine animosity expressed after Hornsby’s departure in 1926, the reconciliation was surprising to some. “I could hardly believe the setting before my eyes was a reality,” Sid Keener wrote in the Star-Times. “Hornsby and Breadon were chatting and making plans again. They had been pals, then enemies, and now they’re pals again.”

A contrite Hornsby told Red Smith, “If I had listened to Mr. Breadon and Mr. Rickey six years ago, I’d be a lot better off today financially and every other way. It’s like coming home. I had disagreements with the Cardinals, but I know Mr. Breadon and Mr. Rickey always treated me fairly.”

Hornsby said to Keener, “I’m willing to admit I made the one big mistake of my career when I slammed the door on Mr. Breadon’s face six years ago and refused to accept the contract that was offered.”

According to the St. Louis newspapers, the Cardinals projected Hornsby as their second baseman for 1933, with Frisch moving either to shortstop or third base.

“We believe Rog is still a great ballplayer,” Breadon said to the Star-Times. “We think he will help us win the pennant next year. That is why we are signing him.”

Rickey told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, “I see no reason why Hornsby can’t have a great year for us.”

Cardinals manager Gabby Street was onboard with the move, too. “Rogers Hornsby is far from being through as a baseball player,” Street said to the Springfield (Mo.) Leader. “I think he’s got a lot left in him and that he’ll be of a real help to the Cardinals.”

Street added, “I don’t anticipate any trouble from him.”

Speculation swirled that Hornsby soon would be lobbying to have Street’s job, but Breadon told the Star-Times that Hornsby had been given “no consideration whatsoever” as a possible successor to Street.

Never a dull moment

Shortly before the 1933 Cardinals started spring training, Hornsby injured his right foot while instructing at a baseball school in Hot Springs, Ark. When the Cardinals opened the regular season against the Cubs at Chicago, Frisch was at second base and Hornsby was on the bench.

Hornsby didn’t appear in either of the Cardinals’ first two games at Chicago, nor did he play in the home-opening series versus the Cubs at St. Louis a week later, but he created controversy with comments accusing Cubs teammates Charlie Grimm and Gabby Hartnett of plotting to get him fired the year before.

According to United Press, Grimm and Hartnett wanted to go into the Cardinals clubhouse at St. Louis and “horsewhip” Hornsby for making what they said were false statements about them, but William Veeck Sr. advised against fighting “a washed up ballplayer.”

In response, Hornsby told the news service, “Whenever Charlie Grimm or Gabby Hartnett want to fight, all they have to do is to roll up their sleeves and come on. I’m ready for them.”

The mood was both tense and electric when the Cardinals returned to Chicago to play a Sunday doubleheader at Wrigley Field on April 30, 1933.

Facing the Cubs for the first time since his firing and for the first time since the war of words with Grimm and Hartnett, Hornsby, 37, started at second base in both games. He had two hits and a RBI and scored a run in the opener, then drove in the winning runs with a two-run home run against Pat Malone in the second game. Game 1 and Game 2.

Hornsby was jeered in every at-bat, but there were no incidents with Cubs players. In the clubhouse after the games, Hornsby displayed “a little extra gleam of satisfaction in his eyes,” the Post-Dispatch noted.

In June, Hornsby had hits in five consecutive plate appearances as a pinch-hitter, including a two-run double that broke a 5-5 tie in a 7-5 victory over the Dodgers. Boxscore

A month later, both the Cardinals and the American League St. Louis Browns made major changes.

On July 19, when their manager, Bill Killefer, resigned, the Browns approached the Cardinals about a replacement. According to the Star-Times, Branch Rickey came to Hornsby and asked, “How would you like to manage the Browns?”

Hornsby replied enthusiastically and accepted Rickey’s offer to negotiate for him.

On July 24, the Cardinals fired Gabby Street and elevated Frankie Frisch to the role of player-manager. Two days later, the Browns hired Hornsby to be their player-manager.

“Mr. Rickey was my guiding adviser throughout the negotiations with the Browns,” Hornsby told the Star-Times. “It may seem peculiar to the fans in St. Louis, but I am indebted to Mr. Rickey for obtaining the position with the Browns. We’ve had many bitter battles in the past, but they’ve been forgotten long ago.”

In 83 at-bats for the 1933 Cardinals, Hornsby had 27 hits and 21 RBI. He batted .325 overall and .333 as a pinch-hitter. His on-base percentage was .423.

“I’ve learned to like him,” Frankie Frisch told the Star-Times, “and I regretted to see him go.”

Instead, his hopes for a storybook ending got washed away on a stormy St. Louis night.

Instead, his hopes for a storybook ending got washed away on a stormy St. Louis night. On Oct. 26, 1972, the Cardinals got outfielder Larry Hisle from the Dodgers for pitchers Rudy Arroyo and Greg Milliken.

On Oct. 26, 1972, the Cardinals got outfielder Larry Hisle from the Dodgers for pitchers Rudy Arroyo and Greg Milliken.

On Oct. 17, 1962, the Cardinals acquired outfielder George Altman, pitcher

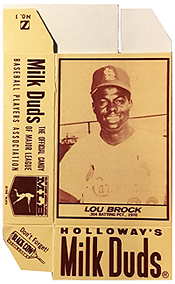

On Oct. 17, 1962, the Cardinals acquired outfielder George Altman, pitcher  In September 1972, the Federal Trade Commission banned a Milk Duds television commercial featuring Brock because it deemed the advertisement as deceptive.

In September 1972, the Federal Trade Commission banned a Milk Duds television commercial featuring Brock because it deemed the advertisement as deceptive.