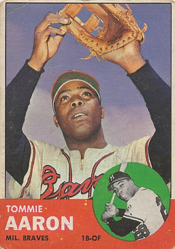

Tommie Aaron, who usually played in the shadow of his older brother, Hank Aaron, got to share the spotlight with him in a game against the Cardinals.

On July 12, 1962, Tommie and Hank each hit home runs in the ninth inning, rallying the Braves to victory versus the Cardinals at Milwaukee.

With the Braves trailing by three runs, Tommie’s solo homer ignited the comeback and Hank’s walkoff grand slam completed it.

Oh, brother

Henry Louis Aaron was born in 1934 in Mobile, Ala. Tommie Lee Aaron was born there five years later.

“I remember seeing Henry play in Mobile,” Tommie told the Atlanta Constitution in 1968, “but I was too young to play on the same team with him.”

Hank Aaron made his big-league debut with the Braves in 1954. He got his first hit, a double, on April 15 against the Cardinals’ Vic Raschi. His first home run came eight days later, also versus Raschi, at St. Louis.

Four years later, John Mullen, who had brought Hank Aaron from the Negro League to the Braves’ organization in 1952, signed Tommie Aaron.

Tommie, like his brother did, batted right-handed. He played first base and outfield. Tommie hit 26 home runs for Eau Claire in 1959 and 20 for Cedar Rapids in 1960.

After batting .299 for Austin in 1961, Tommie made the leap from Class AA to the majors with the Braves in 1962, joining his brother on a team for the first time. Hank already had won a National League Most Valuable Player Award, two batting titles and three Gold Glove honors for his outfield play.

Tommie made the team as the backup to first baseman Joe Adcock. Another Braves rookie that season was a catcher, Bob Uecker.

In his major-league debut, against the Giants at San Francisco, Tommie got a single against Juan Marichal. Boxscore

“He has really impressed me as a good hitter,” Hank Aaron said to The Sporting News. “He does not fall away from the plate. He hangs right in there.”

On May 30, 1962, at Milwaukee, Tommie and Hank combined to give the Braves a victory against the Reds. With the score tied at 3-3, Tommie led off with a single against Dave Sisler, moved to second on a bunt and scored on Hank’s single. Boxscore

Two weeks later, on June 12 at Milwaukee, Hank and Tommie hit home runs in the same game for the first time. Hank’s solo homer came in the second inning against Phil Ortega, and Tommie’s two-run homer was in the eighth versus Ed Roebuck. Boxscore

Fantastic finish

Exactly a month later, Tommie and Hank hit their ninth-inning home runs against the Cardinals.

With one out and none on, Tommie, batting for pitcher Claude Raymond, hit the first pitch from starter Larry Jackson into the bleachers in left-center at County Stadium, cutting the Cardinals’ lead to 6-4.

After Roy McMillan singled, Lindy McDaniel relieved Jackson. McDaniel hadn’t allowed an earned run since May 31, but the Braves were unfazed. Mack Jones singled and Eddie Mathews walked, loading the bases for Hank Aaron.

Hobbling because of an ankle ailment, Aaron worked the count to 2-and-1 against McDaniel. “If he had been ahead of Henry, with two strikes, he would have thrown a forkball,” Cardinals pitching coach Howie Pollet told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

Instead, McDaniel delivered a fastball, and Hank hit it deep, “almost a duplicate of the kid brother’s towering poke over the left-center fence,” the Post-Dispatch reported. Boxscore

The game-winning home run was Aaron’s third grand slam of the season. He totaled 16 grand slams in his career.

Tommie and Hank Aaron became the first brothers to hit home runs in the same inning of a big-league game since Sept. 15, 1938, when Lloyd and Paul Waner did it for the Pirates in the fifth inning against the Giants’ Cliff Melton at the Polo Grounds in New York. Boxscore

Highs and lows

Tommie Aaron had a terrific August for the 1962 Braves, filling in at first base after Adcock got hurt. For the month, Tommie hit .333 and had a .423 on-base percentage. He had 28 hits and 13 walks in 27 games in August.

On Aug. 4, Tommie hit a walkoff grand slam against Jack Baldschun, giving the Braves a 7-3 victory over the Phillies. Boxscore

Ten days later, Tommie and Hank hit home runs in the same game for the third and last time. Facing the Reds at Cincinnati, Tommie’s solo homer came against Johnny Klippstein in the sixth, and Hank followed with a solo homer versus Ted Wills in the seventh. Boxscore

Tommie completed his rookie season with 20 doubles, eight home runs and a. 231 batting mark. It turned out to be the best of his seven seasons in the majors, all with the Braves.

Asked in 1968 about whether he’d offered advice to Tommie, Hank told the Atlanta Constitution, “I’ve talked to him about hitting, but you can’t tell a fellow how to hit. I tell him what I know about certain pitchers, things like that. I’ve talked to him more about his weight. That’s been his biggest problem. He has to watch his weight.”

Hank and Tommie hold the record for most career home runs (768) in the majors by brothers. Hank hit 755 of those.

“You couldn’t possibly compare Hank and me,” Tommie told Milt Richman of United Press International. “We’re two different style ballplayers. He is the complete ballplayer. He can do just about anything. I had to scuffle to do it.”

Mentor to many

In June 1973, Tommie Aaron, 33, was named manager of the Braves’ farm club in Savannah, Ga. He became the first black manager of a professional baseball team in the state and the first in the Southeast, according to the Atlanta Constitution.

Tommie managed in the Braves’ system from 1973-78. Dale Murphy played for him as a catcher with Savannah in 1976 and with Richmond in 1977.

In 1979, Tommie returned to the majors as a Braves coach on the staff of manager Bobby Cox. When Joe Torre became Braves manager in 1982, he kept Tommie Aaron on a coaching staff that included Bob Gibson and Dal Maxvill.

In May 1982, results of a routine annual physical exam showed Tommie Aaron had leukemia. He died on Aug. 16, 1984, two weeks after turning 45.

Braves general manager John Mullen, who some 30 years earlier had signed Tommie and his brother, told the Atlanta Constitution, “He was just a tremendous person with an awful lot of influence on a lot of ballplayers’ lives.”

Among those attending the funeral in Mobile were Hank Aaron, Mullen, Torre and Murphy. Pallbearers included former Braves outfielder Ralph Garr, along with former big-leaguers and Mobile natives Tommie Agee and Cleon Jones.

He helped the Pirates, Dodgers and Cardinals win National League pennants. He played 19 seasons in the majors. He was the second of four generations in his family to play pro baseball.

He helped the Pirates, Dodgers and Cardinals win National League pennants. He played 19 seasons in the majors. He was the second of four generations in his family to play pro baseball. A right-handed sinkerball specialist, Bauta was a Pirates prospect when the Cardinals acquired him and second baseman

A right-handed sinkerball specialist, Bauta was a Pirates prospect when the Cardinals acquired him and second baseman  On July 31, 2012, the Cardinals acquired pitcher Edward Mujica from the Marlins for minor-league third baseman Zack Cox.

On July 31, 2012, the Cardinals acquired pitcher Edward Mujica from the Marlins for minor-league third baseman Zack Cox. On July 29, 2002, the Cardinals traded for Rolen, acquiring the third baseman, along with pitcher Doug Nickle, from the Phillies for infielder Placido Polanco and pitchers

On July 29, 2002, the Cardinals traded for Rolen, acquiring the third baseman, along with pitcher Doug Nickle, from the Phillies for infielder Placido Polanco and pitchers