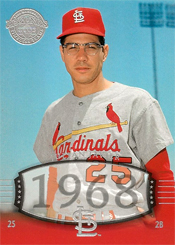

John Cumberland was a teenager from Maine who yearned to play professional baseball. A Cardinals scout took him to dinner and launched him on a path to becoming a big-league pitcher and coach.

A left-hander, Cumberland made his debut in the majors with the Yankees. He later joined Juan Marichal and Gaylord Perry as a starter for the division champion Giants, and got his last win in the big leagues as a reliever with the Cardinals.

A left-hander, Cumberland made his debut in the majors with the Yankees. He later joined Juan Marichal and Gaylord Perry as a starter for the division champion Giants, and got his last win in the big leagues as a reliever with the Cardinals.

As a coach, Cumberland mentored 18-year-old Dwight Gooden in the minors, and was the first big-league pitching coach for Zack Greinke with the Royals.

Bargain player

Born and raised in Westbrook, Maine, Cumberland was a high school baseball and football player. Though he wasn’t selected in the amateur baseball draft, Cumberland’s ability to throw hard impressed Cardinals scout Jeff Jones. According to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Jones bought Cumberland a steak dinner and got him to sign with the Cardinals in 1966.

“I got 52 scholarships out of high school, mostly for football, but the opportunity came up for baseball, so I signed for a steak dinner,” Cumberland recalled to the Clearwater (Fla.) Times. “What a dummy. If I’d waited a little longer, I could have gotten $30,000 or $40,000, even back then. I was anxious, though, for the publicity and all.”

Cumberland was assigned to the Eugene (Ore.) Emeralds, a minor-league club stocked with Cardinals and Phillies prospects. According to the Post-Dispatch, his roommate at Eugene was another future big-league pitcher, Reggie Cleveland.

After posting a 4-1 record for Eugene, Cumberland was taken by the Yankees in the November 1966 minor-league draft.

Two years later, he made his big-league debut for the Yankees against the Red Sox. The first batter he faced, Carl Yastrzemski, grounded a comebacker to Cumberland, who threw to first baseman Mickey Mantle for the out. Boxscore

After making two appearances with the 1969 Yankees, Cumberland got a chance to stick with them in 1970. He got his first big-league win, pitching 6.1 innings of relief against the Senators, and also stroked his first big-league hit, a single that scored Thurman Munson, in that game. Boxscore

The performance earned him a spot in the starting rotation. A month later, in a start against the Indians at Cleveland, Cumberland became the first Yankees pitcher to give up five home runs in a game. Ray Fosse and Tony Horton hit two apiece, and Jack Heidemann slugged the other. Boxscore

In his next start, against the White Sox at Yankee Stadium, Cumberland recovered and pitched his first complete game in the majors, a 3-1 victory. Boxscore

In July 1970, the Yankees traded him to the Giants for pitcher Mike McCormick.

Wakeup call

Soon after joining the Giants, Cumberland was demoted to the minors “with instructions to lose 15 pounds and gain a new pitch,” the New York Daily News reported.

“Getting sent down was the big blow,” Cumberland told reporter Phil Pepe. “It shook me up. I was kind of complacent until that happened. It made me think about my future.”

Cumberland worked on improving his curveball. Called up by the Giants in September, he was 2-0 with a 0.00 ERA in five relief appearances that month.

Pleasant surprise

In 1971, Cumberland entered spring training 15 pounds lighter than he was the previous year, and earned an Opening Day roster spot as a reliever.

When Frank Reberger got injured, Giants manager Charlie Fox chose Cumberland to start against the Cubs on June 22. He beat Ferguson Jenkins in a 2-0 duel. Boxscore

Cumberland remained in the rotation, and on July 3 he pitched a four-hitter, beating Steve Carlton and the Cardinals. Boxscore

“Cumberland is perhaps the most unartistic-looking left-handed pitcher since Hal Woodeshick went into retirement,” San Francisco columnist Wells Twombley observed.

The results, though, were effective. Cumberland was 9-6 for the 1971 Giants, who won a division title. He ranked second on the team in ERA (2.92) and third in innings pitched (185).

“He’s been the biggest surprise of the season,” Fox told United Press International. “What I like best about him is the way he battles the batters. He’s a real bulldog.”

Winding down

At spring training in 1972, teammate Juan Marichal worked with Cumberland on developing a screwball. After posting a 1.61 ERA in 28 exhibition game innings _ “My best spring training ever,” he told the Post-Dispatch _ Cumberland seemed poised to succeed in the regular season, but the opposite happened.

Cumberland was 0-4 with an 8.64 ERA for the Giants when they arrived in St. Louis on June 16, 1972, for a series with the Cardinals. Before the game that night, the Giants swapped Cumberland to the Cardinals for minor-league infielder Jeffrey Mason.

“He’s only 25 and has good control,” Cardinals manager Red Schoendienst told the Post-Dispatch. “If he can come along with that screwball, he could really help us.”

In his St. Louis debut, a start versus the Expos and former Cardinal Mike Torrez, Cumberland gave up six runs in 3.1 innings. Boxscore

After that, Schoendienst used Cumberland as a reliever.

On Aug. 19, facing the Giants in San Francisco, Cumberland pitched three innings and got the win, his last in the majors. Boxscore

“I can’t think of any club I’d rather beat,” Cumberland told the Oakland Tribune.

In 14 games with the 1972 Cardinals, Cumberland was 1-1 with a 6.65 ERA. After the season, they dealt him and outfielder Larry Hisle to the Twins for reliever Wayne Granger.

Helping hand

Cumberland’s final season in the majors was 1974. Eight years later, the Mets hired him to be a coach in the minors.

At the Lynchburg, Va., farm club in 1983, teen phenom Dwight Gooden got off to a mediocre start and was challenged by Cumberland.

“I just told him I didn’t think he wanted to win, and that he wasn’t much of a competitor,” Cumberland told the Newport News Daily Press.

According to Cumberland, Gooden responded, “You were right. I was too timid. That will never happen again.”

Gooden finished 19-4 with 300 strikeouts in 191 innings for Lynchburg.

At the Florida Instructional League after the season, Cumberland helped Gooden develop a changeup and worked with him to shorten his motion.

Cumberland coached in the Mets system from 1982-90. Others he mentored included Rick Aguilera, Randy Myers and Calvin Schiraldi.

“He was the best pitching coach we had in the minor leagues,” Mets scouting director Joe McIlvaine told the Boston Globe. “He toughened the kids up. He worked better with the mind of the player than with the body of the player. That’s a hard thing to get. When we sent a pitcher to John Cumberland in the minor leagues, he was always better for the experience.”

In addition to stints as a minor-league coach for the Padres and Brewers, Cumberland coached in the big leagues with the Red Sox and Royals.

When he was Red Sox pitching coach in 1995, the staff included Roger Clemens, and future Cardinals pitching coaches Derek Lilliquist and Mike Maddux. Derek Lowe transformed from starter to closer while Cumberland was Red Sox bullpen coach from 1999-2001.

Cumberland was Royals pitching coach for manager Tony Pena from 2002-04. When Zack Greinke, 20, made his big-league debut in 2004, he reminded Cumberland of Gooden at a similar age.

“Dwight was more of a power pitcher,” Cumberland told the Kansas City Star, “but the two have the same type of makeup: ‘Here I am. I’m not intimidated. Stand in the box. I’m going to get you out.’ That’s the way Dwight was at 18, just like this kid.”

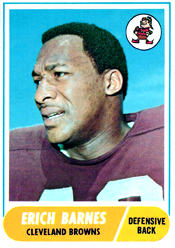

Two of Barnes’ most significant clashes with the Cardinals occurred in consecutive seasons (1966 and 1967) at St. Louis. The first illustrated his fiery intensity. The second showed his smarts.

Two of Barnes’ most significant clashes with the Cardinals occurred in consecutive seasons (1966 and 1967) at St. Louis. The first illustrated his fiery intensity. The second showed his smarts.

Three times in his career, Javier hit a home run in a 1-0 Cardinals victory. The only other player to hit a home run in three 1-0 Cardinals triumphs is Ken Boyer, according to researcher Tom Orf.

Three times in his career, Javier hit a home run in a 1-0 Cardinals victory. The only other player to hit a home run in three 1-0 Cardinals triumphs is Ken Boyer, according to researcher Tom Orf. The final time Boyer hit a home run in a 1-0 Cardinals win was June 25, 1960, at Philadelphia. Leading off the ninth, he lined the first pitch from Jim Owens just over a railing into the first row of seats in left at Connie Mack Stadium.

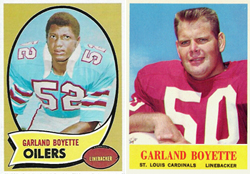

The final time Boyer hit a home run in a 1-0 Cardinals win was June 25, 1960, at Philadelphia. Leading off the ninth, he lined the first pitch from Jim Owens just over a railing into the first row of seats in left at Connie Mack Stadium. Two years later, the Cardinals cut him, but that wasn’t the only insult he endured. Philadelphia Chewing Gum Corporation produced a football card of Boyette that year, but fumbled the assignment. The name on the card was Garland Boyette, but the photo was of Don Gillis, a former Cardinals center who no longer was in the league. Boyette was black and Gillis was white.

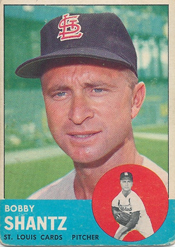

Two years later, the Cardinals cut him, but that wasn’t the only insult he endured. Philadelphia Chewing Gum Corporation produced a football card of Boyette that year, but fumbled the assignment. The name on the card was Garland Boyette, but the photo was of Don Gillis, a former Cardinals center who no longer was in the league. Boyette was black and Gillis was white. On May 7, 1962, the Cardinals traded pitcher John Anderson and outfielder Carl Warwick to the Houston Colt .45s for Shantz.

On May 7, 1962, the Cardinals traded pitcher John Anderson and outfielder Carl Warwick to the Houston Colt .45s for Shantz.