Diego Segui brought much-needed relief to the Cardinals.

On June 7, 1972, the Cardinals bought the contract of Segui from the Athletics.

On June 7, 1972, the Cardinals bought the contract of Segui from the Athletics.

A right-hander whose best pitch was a forkball, Segui gave the Cardinals a quality closer. Before acquiring him, the 1972 Cardinals totaled one save. The year before, their save leader had eight.

As the St. Louis Post-Dispatch noted, Segui “arrived to breathe life into a bullpen that had been horrible.”

From ranch to diamond

Segui was born and raised in southeastern Cuba near the seaport city of Santiago. His father was a ranch foreman who taught his son to rope horses and cattle. “I was pretty good with a lasso,” Segui told the Post-Dispatch.

The work strengthened his hands and helped Segui become a pitcher able to grip a variety of pitches.

He was 20 and pitching for the Tucson Cowboys of the Arizona-Mexico League when the Kansas City Athletics signed him on the recommendation of their scout, former big-league outfielder Al Zarilla. Segui entered their farm system in 1959 and reached the majors with the Athletics in 1962.

While with Kansas City, Segui met the woman he married, Emily. They were introduced by the mother of Athletics catcher Joe Azcue.

Segui developed a forkball, so named because the ball was held in the fork of the hand, between the forefinger and middle finger.

“A pitcher must have reasonably long and flexible fingers to throw the forkball, which is one reason it is not a common pitch,” the Kansas City Star noted. “The forkball is thrown with the same motion as a fastball, but the velocity is much slower and the ball breaks down as it reaches the plate.”

Segui pitched at a deliberate pace. As the Oakland Tribune observed, “He rubs up the ball between every pitch _ even during intentional walks _ straightens out the Virgin Mary medallion he wears around his neck, counts his fielders, steps off the mound to blow on his hand, and smooths the dirt in front of the rubber.”

Come and go

Segui pitched for Kansas City from 1962-65, got traded to the Senators, spent 1966 with them and was reacquired by the Athletics.

After two more seasons with the Athletics, Segui was selected by the Seattle Pilots in the American League expansion draft, pitched in their first regular-season game and finished the season with 12 wins and 12 saves. Boxscore

The Athletics, who had relocated to Oakland, reacquired him again, and Segui posted a 2.56 ERA, best in the American League, for them in 1970.

Rich with starting pitching (Catfish Hunter, Vida Blue, Ken Holtzman) and relievers (Rollie Fingers, Bob Locker, Darold Knowles) in 1972, their first of three consecutive World Series championship seasons, the Athletics didn’t have enough work for Segui, prompting the deal with the Cardinals.

When informed he’d be leaving the Athletics for the third time, Segui told the Oakland Tribune, “Maybe I’ll get a chance to pitch for St. Louis, but I would rather have stayed on this club and not pitched.”

Good impression

Segui’s perspective changed after he experienced immediate success with the Cardinals. In his National League debut, he pitched three scoreless innings against the Giants and got the win. Boxscore

“He has a hard slider that breaks at the last second,” Cardinals catcher Ted Simmons told the San Francisco Examiner. “His forkball is murder on a left-handed batter, dropping off the table.”

Two nights later, Segui got his first Cardinals save with 1.2 scoreless innings versus the Padres. Boxscore

“When a guy can throw strikes and has an out pitch like his forkball, you’re in business,” Simmons told the Post-Dispatch. “Segui has a fantastic forkball. It looks like a fastball to the batter, and before you know it, wham, the ball is by you.”

Orioles scout Jim Russo told columnist Bob Broeg, “In Segui, they’ve got one of their best pickups of late. He’s a nice guy, a good man on a club, and he knows how to pitch.”

Segui, who turned 35 two months after joining the Cardinals, finished the 1972 season as the team leader in saves (nine) and relief outings (33). He was 3-1 with a 3.07 ERA. Batters hit .184 against him with runners in scoring position. Video at 30-second mark

Say hey, Segui

Segui followed up with a strong season for St. Louis in 1973. He led the club in saves (17) and games pitched (65), posting a 7-6 record and 2.78 ERA. He struck out 93 in 100.1 innings and allowed a mere 78 hits.

“You wish you had 25 men like him,” Cardinals player personnel director Bob Kennedy told the Post-Dispatch. Kennedy was Segui’s manager with the 1968 Athletics.

“You couldn’t ask for a better guy,” Kennedy said. “He’s one of the finest men I’ve known in baseball.”

Segui had a couple of interesting matchups in 1973 with Willie Mays, 42, who was with the Mets in the final season of his Hall of Fame career.

On July 26 at St. Louis, with the Cardinals ahead, 2-1, in the ninth, the Mets had a runner on base, two outs, when Segui struck out Mays on a forkball to end the game. Boxscore

A week later, on Aug. 3 at New York, Mays, batting .207 for the season, faced Segui in the seventh, with two on, two outs and the Mets ahead, 4-3. Mays got a low inside fastball from Segui and hit it over the wall in center for a three-run home run. Boxscore

“I was just looking for something fast, and there it was,” Mays said to the Associated Press.

The home run was the 659th of Mays’ career. He hit his last, No. 660, two weeks later against Don Gullett of the Reds.

Family and fishing

After the season, the Cardinals swapped Segui, pitcher Reggie Cleveland and infielder Terry Hughes to the Red Sox for pitchers John Curtis, Mike Garman and Lynn McGlothen.

“Segui really did a job for us,” Cardinals manager Red Schoendienst told the Boston Globe, but he said Segui became expendable with the emergence of Al Hrabosky as a potential closer.

Segui pitched in a World Series with the Red Sox in 1975.

His final season in the majors was in 1977 with the expansion Seattle Mariners. Segui, who turned 40 that year, was their Opening Day starting pitcher. Naturally, he was called the “Ancient Mariner.” Boxscore

Segui is the only player to appear in games for both the Seattle Pilots and Seattle Mariners.

He continued to pitch professionally until 1984, when he turned 47 and earned 10 wins for Leon, a Mexican League team managed by ex-Cardinal Benny Valenzuela.

Diego and Emily Segui raised four children. One of them, David, played 15 seasons in the majors, just like his father did. Primarily a first baseman, David hit .291 for his career.

When David was a youngster, his father played baseball all year, including winters in the Caribbean. To fill the void, Emily would “play catch in the backyard and hit fungoes to David to help him work on his defensive skills,” the New York Times reported.

“All the credit must go to my wife,” Diego told the New York Daily News. “If my wife never takes him to play, and hitting ground balls, he would never be what he is.”

After seven years as a minor-league pitching coach for the Giants, Diego Segui retired in Kansas City and pursued his lifelong passion for fishing. He became an accomplished bass fisherman who excelled in local tournaments.

“In March, I won $2,200 for catching one fish,” Segui told the Kansas City Star in 1998. “When I broke into the big leagues, I made $6,000 a year. I made more in one cast than I would make in four months back in those days.”

On June 4, 1932, the Cardinals purchased Reese’s contract from the minor-league St. Paul Saints.

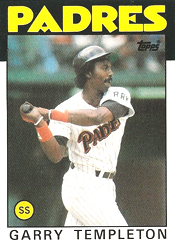

On June 4, 1932, the Cardinals purchased Reese’s contract from the minor-league St. Paul Saints. In May 1982, Templeton was with the Padres when they played a series versus the Cardinals at Busch Memorial Stadium. Templeton hadn’t been to St. Louis since being

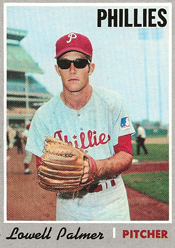

In May 1982, Templeton was with the Padres when they played a series versus the Cardinals at Busch Memorial Stadium. Templeton hadn’t been to St. Louis since being  Palmer wore shades when he pitched, not to look cool, but because his eyes were highly sensitive to light. To a batter peering from the plate to the mound, the sight of a hard thrower with erratic control in a pair of black sunglasses could be unsettling, if not intimidating.

Palmer wore shades when he pitched, not to look cool, but because his eyes were highly sensitive to light. To a batter peering from the plate to the mound, the sight of a hard thrower with erratic control in a pair of black sunglasses could be unsettling, if not intimidating. “He has sensitive eyes, so he wears dark glasses that look as though they were carved out of chunks of bituminous coal when he pitches,” Stan Hochman wrote in the Philadelphia Daily News.

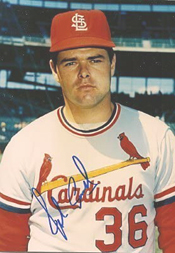

“He has sensitive eyes, so he wears dark glasses that look as though they were carved out of chunks of bituminous coal when he pitches,” Stan Hochman wrote in the Philadelphia Daily News. A left-hander, Cumberland made his debut in the majors with the Yankees. He later joined Juan Marichal and Gaylord Perry as a starter for the division champion Giants, and got his last win in the big leagues as a reliever with the Cardinals.

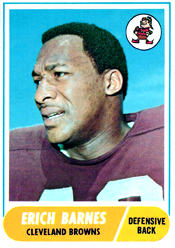

A left-hander, Cumberland made his debut in the majors with the Yankees. He later joined Juan Marichal and Gaylord Perry as a starter for the division champion Giants, and got his last win in the big leagues as a reliever with the Cardinals. Two of Barnes’ most significant clashes with the Cardinals occurred in consecutive seasons (1966 and 1967) at St. Louis. The first illustrated his fiery intensity. The second showed his smarts.

Two of Barnes’ most significant clashes with the Cardinals occurred in consecutive seasons (1966 and 1967) at St. Louis. The first illustrated his fiery intensity. The second showed his smarts.