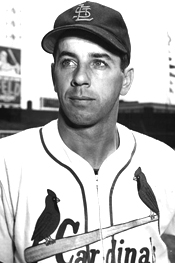

Even when he was their teammate, Stan Rojek was battered and bruised by Cardinals pitching.

On May 17, 1951, the Cardinals acquired Rojek, a shortstop, from the Pirates for outfielder Erv Dusak and first baseman Rocky Nelson.

On May 17, 1951, the Cardinals acquired Rojek, a shortstop, from the Pirates for outfielder Erv Dusak and first baseman Rocky Nelson.

Two years earlier, while with the Pirates, Rojek was hit by pitches twice in a game against the Cardinals. The second one struck him in the head and put him in the hospital.

After he got sent to the Cardinals, the danger didn’t dissipate. One of their pitchers plunked him during batting practice, cracking a shoulder blade and ending his season.

Pirate in pain

Born and raised in North Tonawanda, N.Y., near Buffalo, Rojek signed with the Dodgers in 1939 and made his debut with them three years later, but he wasn’t going to displace Pee Wee Reese at shortstop.

In November 1947, the Dodgers dealt Rojek to the Pirates and he became their shortstop. Rojek batted .290 for the 1948 Pirates and ranked third in the National League in hits (186).

The next year, on April 27, 1949, in the Pirates’ first visit of the season to St. Louis, Rojek was hit in the back by a Gerry Staley pitch in the fifth inning. In the bottom half of the inning, while turning a double play, Rojek’s low, underhand toss to first came close to striking baserunner Red Schoendienst. The Cardinals accused Rojek of trying to hit Schoendienst, but Rojek laughed at the suggestion, according to The Pittsburgh Press.

In the seventh, Cardinals baserunner Joe Garagiola slid into Rojek at second and Rojek stepped on him with his spikes, The Sporting News reported.

When Rojek batted in the ninth, the first pitch from Ken Johnson was high and inside, brushing him off the plate.

“I didn’t think he’d try to knock me down a second time after brushing me back on the first pitch,” Rojek said, according to The Pittsburgh Press. “So I dug in for what I thought would be a pitch on the outside corner.”

Instead, Johnson’s second pitch headed toward Rojek’s head. “When I saw the ball coming at me, it was too late to duck out of the way,” said Rojek.

The ball hit Rojek flush on the left ear. He wore neither a batting helmet nor a protective lining in his cap.

According to The Sporting News, Rojek dropped his bat and staggered toward the first-base line “with blood coming out of his ear.” As Pirates rushed from the dugout to his aid, Rojek was a few feet from the plate when he fell into the arms of teammate Eddie Stevens, who gently laid him on the ground.

As the Pirates waited for a stretcher to arrive, they confronted Johnson and Garagiola, accusing the pitcher and catcher of conspiring to bean Rojek.

According to The Sporting News, Johnson replied, “I’m only the pitcher.” To some, his response indicated Garagiola called the pitch. Garagiola “was so nervous and afraid that he almost cried,” The Sporting News reported.

Rojek was taken into the clubhouse to await an ambulance. When the game ended, Cardinals manager Eddie Dyer went to see Rojek and said, “I’m sorry, Stan. I hope it’s nothing serious.”

According to The Pittsburgh Press, a groggy Rojek replied, “Thanks, Eddie.”

Some Pirates were unmoved and exchanged harsh words with Dyer. Outfielder Wally Westlake told Dyer, “Get the hell out of here with your apologies,” The Pittsburgh Press reported. Boxscore

Owning the plate

At the hospital, X-rays showed Rojek suffered a concussion, but no fracture. He had swelling under his ear and two stitches were required to close the wound.

Johnson called Rojek at the hospital the next morning and said he never intended to hurt him.

Some suggested Rojek put himself at risk because of a batting stance “in which his head is almost over the inside corner of the plate,” The Pittsburgh Press noted.

Phillies pitcher Schoolboy Rowe told The Sporting News that Rojek “hogs the plate, leans over it as if he were trying to count the specks of dust on it.”

National League president Ford Frick said umpires determined Johnson was not throwing at Rojek. “They even pointed out that the ball was almost a strike, but because Rojek was crouched over the plate, it hit him in the head,” Frick said. “Stan just froze up there, they said.”

Rojek returned to the Pirates’ lineup a week later. For the season, he hit .244.

In 1950, the Pirates platooned Rojek and Danny O’Connell at shortstop. The next year, at spring training, George Strickland won the shortstop job and Rojek was deemed expendable.

Bad break

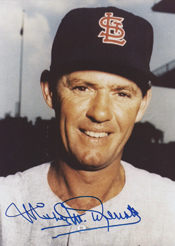

The Cardinals needed help at shortstop in 1951. Marty Marion, who played the position from 1940-50, became their manager in 1951 and was unable to continue playing because of a knee ailment.

At spring training, reserve second baseman Solly Hemus volunteered to play shortstop. The Cardinals opened the season with him, but when he struggled to hit they sought an alternative.

The Cardinals acquired Rojek, 32, at Marion’s request.

Platooning with Hemus, Rojek took advantage of the opportunity, hitting safely in 13 of the first 14 games he played for the Cardinals.

Three months later, during batting practice on Aug. 8, Cardinals pitcher Red Munger hit Rojek with a pitch, cracking his left shoulder blade. Done for the season, Rojek was sent home. He hit .274 in 51 games for the Cardinals and .319 with runners in scoring position.

Hemus surged after Rojek departed and hit .281 for the season.

Projecting Hemus to remain their shortstop in 1952, the Cardinals sent Rojek to the Browns for the $10,000 waiver price in January 1952.

On May 12, 1981, a squeeze bunt by Tommy Herr scored Gene Tenace with the go-ahead run, and Jim Kaat retired the side in order in the bottom half of the inning, carrying the Cardinals to a 3-2 victory over the Astros.

On May 12, 1981, a squeeze bunt by Tommy Herr scored Gene Tenace with the go-ahead run, and Jim Kaat retired the side in order in the bottom half of the inning, carrying the Cardinals to a 3-2 victory over the Astros. On April 28, 1961, Schoendienst, a pinch-hitter, stroked a two-run double against Green in the 11th inning, lifting the Cardinals to a 10-9 walkoff victory versus the Phillies at St. Louis.

On April 28, 1961, Schoendienst, a pinch-hitter, stroked a two-run double against Green in the 11th inning, lifting the Cardinals to a 10-9 walkoff victory versus the Phillies at St. Louis. On April 23, 1961, at Candlestick Park, McDermott got a three-run pinch-hit double in the top of the ninth, giving the Cardinals the lead, and stayed in the game to pitch the bottom half of the inning, setting down the Giants in order for the save.

On April 23, 1961, at Candlestick Park, McDermott got a three-run pinch-hit double in the top of the ninth, giving the Cardinals the lead, and stayed in the game to pitch the bottom half of the inning, setting down the Giants in order for the save.

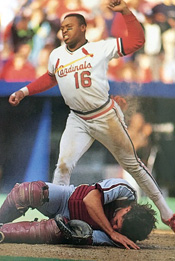

On April 21, 1991, Lankford scored the winning run for the Cardinals against the Phillies when he raced from second base to the plate on an infield out, barreling into Darren Daulton and jarring the ball loose from the mitt of the dazed catcher.

On April 21, 1991, Lankford scored the winning run for the Cardinals against the Phillies when he raced from second base to the plate on an infield out, barreling into Darren Daulton and jarring the ball loose from the mitt of the dazed catcher.