(Updated May 8, 2021)

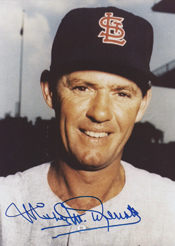

As managers, Red Schoendienst and Dallas Green led teams to World Series championships. As players, they faced one another with the outcome of a game on the line.

On April 28, 1961, Schoendienst, a pinch-hitter, stroked a two-run double against Green in the 11th inning, lifting the Cardinals to a 10-9 walkoff victory versus the Phillies at St. Louis.

On April 28, 1961, Schoendienst, a pinch-hitter, stroked a two-run double against Green in the 11th inning, lifting the Cardinals to a 10-9 walkoff victory versus the Phillies at St. Louis.

Schoendienst, 38, was in his first season back with the Cardinals after being traded by them in June 1956. Green, 26, was in his second season in the majors and trying to overcome persistent shoulder and arm ailments.

After their playing careers, Schoendienst managed the Cardinals to a World Series title in 1967 and Green did the same for the Phillies in 1980.

Heading home

A second baseman of Hall of Fame caliber with the Cardinals, Giants and Braves, Schoendienst was at a career crossroads in 1961. He sat out most of the 1959 season while recovering from tuberculosis and was released by the Braves in October 1960.

Angels general manager Fred Haney, who managed the Braves to a World Series championship in 1957 when Schoendienst was the second baseman, offered him a contract to play for the American League expansion team in 1961. Schoendienst almost accepted, but opted instead for an invitation to spring training with the Cardinals.

Schoendienst was issued uniform No. 16 because the No. 2 he wore for most of his first stint with the Cardinals belonged to catcher Hal Smith. Smith voluntarily gave No. 2 back to Schoendienst.

“When Red was with the Cardinals the first time, he wore No. 2 and had two children,” Smith told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. “When he was with the Braves, he wore No. 4 and had four children. When he came back to the Cardinals, he was given No. 16, so ….”

Schoendienst made the Opening Day roster, accepting a role as pinch-hitter and backup to second baseman Julian Javier.

“Don’t write me off,” Schoendienst said to The Sporting News. “This is too much fun. I’m not ready to throw in the towel.”

Clutch hit

A switch-hitter, Schoendienst had a sizzling start to the 1961 season, hitting .348 in April.

Dallas Green also did well early for the Phillies. A right-hander, he earned a spot in the starting rotation and pitched a shutout against the Giants in his first appearance of the season.

“For the first time in several years, I can throw without pain,” Green told The Sporting News. “You just can’t imagine what a feeling it is to be able to let go again.”

When the Phillies and Cardinals played on April 28, a raw, chilly Friday night at Busch Stadium, the starting pitchers were Robin Roberts and Ernie Broglio. The Cardinals led 6-1 after four innings, but the Phillies rallied. The game went to extra innings and the Phillies went ahead, 9-8, in the 11th.

Green, the Phillies’ seventh pitcher of the game, was working his third inning when the Cardinals loaded the bases with one out in the 11th.

Sent to bat for pitcher Al Cicotte, Schoendienst lined a double into the right-field corner, scoring Carl Sawatski and Alex Grammas.

“A good pitch, a slider, I think,” Schoendienst said to the Post-Dispatch. Boxscore

Getting it done

Three months later, on July 6, when the Cardinals fired manager Solly Hemus and replaced him with coach Johnny Keane, Schoendienst was added to the staff as player-coach.

Schoendienst led by example, becoming “one of the best pinch-hitters in the business,” the Post-Dispatch noted.

For the season, Schoendienst hit .347 as a pinch-hitter and .300 overall. In 54 plate appearances as a pinch-hitter, his on-base percentage was .407.

In 133 plate appearances overall in 1961, Schoendienst had six strikeouts, or one out of 22 times. No other Cardinal whiffed so infrequently in 1961, The Sporting News reported. Only once did he hit into a double play during the season.

Schoendienst continued as a player-coach for Keane in 1962, hitting .306 as a pinch-hitter and .301 overall.

He began the 1963 season in the same role, but after going hitless in six plate appearances, the Cardinals opted to remove Schoendienst from the player roster. According to Cardinals Gameday Magazine, general manager Bing Devine informed Schoendienst he could remain with the Cardinals as a coach or make his own deal to sign with another club as a player.

“I’ve talked to five clubs,” Devine told Schoendienst. “They all said they want you.”

Schoendienst chose to stay as a coach, ending his playing days.

For his big-league career, Schoendienst had better numbers as a pinch-hitter (.305 batting average and .371 on-base percentage) than he did overall (.289 batting average and .337 on-base percentage).

On April 23, 1961, at Candlestick Park, McDermott got a three-run pinch-hit double in the top of the ninth, giving the Cardinals the lead, and stayed in the game to pitch the bottom half of the inning, setting down the Giants in order for the save.

On April 23, 1961, at Candlestick Park, McDermott got a three-run pinch-hit double in the top of the ninth, giving the Cardinals the lead, and stayed in the game to pitch the bottom half of the inning, setting down the Giants in order for the save.

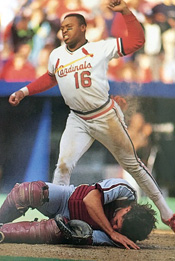

On April 21, 1991, Lankford scored the winning run for the Cardinals against the Phillies when he raced from second base to the plate on an infield out, barreling into Darren Daulton and jarring the ball loose from the mitt of the dazed catcher.

On April 21, 1991, Lankford scored the winning run for the Cardinals against the Phillies when he raced from second base to the plate on an infield out, barreling into Darren Daulton and jarring the ball loose from the mitt of the dazed catcher.

Playing with confidence and aggressiveness, Reitz, 21, fielded smoothly and hit for average, convincing the Cardinals he was ready to be their third baseman.

Playing with confidence and aggressiveness, Reitz, 21, fielded smoothly and hit for average, convincing the Cardinals he was ready to be their third baseman.