(Updated March 5, 2022)

An injury to Tommy Herr opened a path to the big leagues with the Cardinals for Rafael Santana.

On Feb. 16, 1981, the Cardinals purchased the contract of Santana, a minor-league infielder, from the Yankees on a conditional basis. The Cardinals wanted to take a look at Santana in training camp before deciding whether to keep him or send him back to the Yankees.

On Feb. 16, 1981, the Cardinals purchased the contract of Santana, a minor-league infielder, from the Yankees on a conditional basis. The Cardinals wanted to take a look at Santana in training camp before deciding whether to keep him or send him back to the Yankees.

After choosing to retain Santana and assigning him to their farm system, the Cardinals agreed to give the Yankees a player to be named as compensation.

Santana remained in the minors the next two seasons and wasn’t prominent in the Cardinals’ plans when spring training began in 1983, but that changed when Herr, their second baseman, got sidelined because of a knee injury.

Santana made the 1983 Cardinals’ Opening Day roster as a backup infielder. A year later, he replaced Jose Oquendo as Mets shortstop. He still was the starter at that position in 1986 when the Mets became World Series champions.

Minor prospect

Born and raised in the Dominican Republic, Santana was 18 when he signed with the Yankees in 1976. He spent four seasons (1977-80) in their farm system, with Class AA being the highest level he reached.

When the Cardinals acquired Santana in 1981, they sent him to their Class AA club at Arkansas. He played shortstop and batted .233 for the season.

For a while that year, it seemed the Cardinals had gotten the worst of the deal.

Go figure

On June 7, 1981, four months after they got Santana, the Cardinals sent pitcher George Frazier, who was with their Springfield, Ill., farm team, to the Yankees as the player to be named, completing the transaction.

According to columnist Dick Young in The Sporting News, the Cardinals and Cubs had agreed to a swap of Frazier for pitcher Doug Capilla in spring 1981, but when Cubs manager Joey Amalfitano objected, the trade was called off. Then the Cardinals sent Frazier to the Yankees.

The move got little attention. A right-hander, Frazier was 3-11 with three saves in parts of three seasons (1978-80) with the Cardinals.

“I had three trials and I really had not done a magnificent job,” Frazier told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. “I was getting to a stagnant situation.”

The Yankees sent him to their farm team in Columbus, Ohio. “I thought I was going from one graveyard to another,” Frazier said.

After Yankees minor-league coach Sammy Ellis changed Frazier’s delivery and taught him to throw a forkball, he thrived. In 27 appearances for Columbus, Frazier was 4-1 with nine saves.

In August 1981, when closer Goose Gossage developed shoulder soreness, the Yankees called up Frazier and he gave the bullpen a boost. In 16 relief appearances for the Yankees, Frazier had three saves and a 1.63 ERA. He also won Game 2 of the American League Championship Series against the Athletics.

The storybook run from Cardinals reject to Yankees standout skidded to a halt in the 1981 World Series. Frazier was the losing pitcher in Games 3, 4 and 6 versus the Dodgers. Unfazed, he told the New York Times, “If I was still with the Cardinals, I’d be home fishing or mending fences. I’d rather be where I am.”

Getting a chance

With Class AAA Louisville in 1982, Santana primarily played third base and also made starts at shortstop and second. A right-handed batter, he impressed the Cardinals by learning to hit to the opposite field. His .286 batting mark was the best he produced since becoming a professional.

When Santana went to spring training in 1983, “it was unlikely” he would make the Cardinals’ Opening Day roster, the Post-Dispatch reported. The defending World Series champions were set at the three positions Santana played. Starters were Herr at second, Ozzie Smith at short and Ken Oberkfell at third. Mike Ramsey was the backup at second and short. Jamie Quirk could fill in at third.

When Herr injured his left knee and needed arthroscopic surgery in March, Ramsey took over at second and the Cardinals sought a backup. The candidates were a pair of rookies: Santana and Kelly Paris.

Santana, 25, emerged as the favorite. One reason: he was out of options. If the Cardinals sent Santana to the minors, he would have to clear waivers before they could recall him. Cardinals manager Whitey Herzog also rated Santana “a better infielder defensively” than Paris, the Post-Dispatch reported.

“What he’s really done is grow up a lot,” Herzog said of Santana. “He’s more mature than he was when we got him.”

The Cardinals opened the 1983 season with Ramsey at second, Herr on the disabled list and Santana as the backup middle infielder.

Coming through

On April 29, 1983, Herr was reinstated to the roster but the Cardinals kept Santana. That night, Santana got his first big-league hit, a single against the Giants’ Jim Barr. Boxscore

Two weeks later, the Cardinals played the Giants again. In the top of the ninth, with the Cardinals trailing by a run, Santana made his fourth plate appearance in the majors, batting with the bases loaded and two outs.

“I wasn’t nervous,” Santana told the Post-Dispatch. “I’m never nervous in this game.”

Santana blooped a two-run single against Gary Lavelle, putting the Cardinals ahead. “I didn’t hit it good,” Santana said. “It was off the end of the bat, but there was nobody there to catch it.”

The Giants rallied for two runs versus Bruce Sutter in the bottom half of the inning and won. Boxscore

On June 16, Ramsey went on the disabled because of a back ailment. When he returned in July, Santana was shipped to Louisville.

Santana played in 30 games for the 1983 Cardinals, made one start at second base and hit .214. At Louisville, he mostly played third and batted .281.

Big Apple adventures

As a veteran of six seasons in the minors, Santana was eligible to become a free agent. Unable to keep him, the Cardinals released him on Jan. 17, 1984.

“He’s not flashy, but he’s always consistent, always makes the plays,” Cardinals director of player development Lee Thomas told the New York Daily News. “That son of a gun made a good hitter out of himself. He wasn’t as good a hitter when we got him as he was when we let him go.”

The Dodgers, Mets and Tigers made Santana offers. “I picked the Mets because I thought I had a better chance with this organization as a utility player,” Santana told the Daily News. “When I signed, I didn’t dream I could become the regular shortstop.”

Jose Oquendo was the Mets’ shortstop, but he fell into disfavor with manager Davey Johnson. “Oquendo can be a great shortstop, but right now he doesn’t know how to play shortstop,” Johnson said to the Daily News. “He has a great arm, but doesn’t know how to use it. Rafael Santana knows how to play shortstop.”

Santana replaced Oquendo as the Mets’ shortstop in July 1984. Nine months later, Oquendo was traded to the Cardinals.

In 1986, Santana’s fielding was a factor in the Mets’ success. He fielded flawlessly in the National League Championship Series versus the Astros and made one error in 58 innings against the Red Sox in the World Series.

After the 1987 season, Santana was traded to the Yankees and he was their shortstop in 1988. After sitting out the 1989 season following elbow surgery, Santana closed his playing career in a brief stint with the Indians.

Santana played in the infield with first baseman Keith Hernandez for three franchises: Cardinals (1983), Mets (1984-87) and Indians (1990).

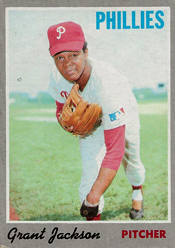

A left-hander, Jackson pitched 18 seasons in the majors.

A left-hander, Jackson pitched 18 seasons in the majors. In 1970, the Pirates’ outfielder and future Hall of Famer revealed he had been abducted at gunpoint a year earlier by four men in San Diego and robbed. Clemente said he thought he would be shot and left for dead. Instead, he said, he was released and his possessions were returned.

In 1970, the Pirates’ outfielder and future Hall of Famer revealed he had been abducted at gunpoint a year earlier by four men in San Diego and robbed. Clemente said he thought he would be shot and left for dead. Instead, he said, he was released and his possessions were returned. In February 1981, Boyer was at Cardinals spring training camp as an instructor, working with players who a year earlier he had managed.

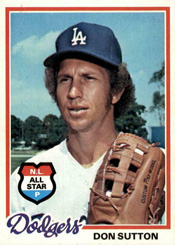

In February 1981, Boyer was at Cardinals spring training camp as an instructor, working with players who a year earlier he had managed. On July 14, 1978, Sutton, the Dodgers’ ace, was ejected by umpire Doug Harvey for pitching a defaced baseball against the Cardinals.

On July 14, 1978, Sutton, the Dodgers’ ace, was ejected by umpire Doug Harvey for pitching a defaced baseball against the Cardinals. On Jan. 11, 1996, the Cardinals signed Gallego, a free agent, for one year at $300,000.

On Jan. 11, 1996, the Cardinals signed Gallego, a free agent, for one year at $300,000.