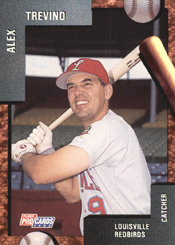

Joe Torre guided Alex Trevino into the majors and was with him again 13 years later when he left.

On Jan. 2, 1991, the Cardinals signed Trevino, a free agent, as backup catcher.

On Jan. 2, 1991, the Cardinals signed Trevino, a free agent, as backup catcher.

The deal reunited Trevino with Torre, the Cardinals’ manager and former catcher. Torre was manager of the Mets when Trevino, 21, made his major-league debut with them in September 1978. Trevino and Torre were together with the Mets for four seasons (1978-81). Trevino also played for Torre in 1984 when Torre was managing the Braves.

Torre and the Cardinals projected Trevino to back up starting catcher Tom Pagnozzi in 1991, but it didn’t work out. Instead, Trevino got released near the end of spring training. The next season, Trevino was back in the Cardinals’ organization and, though he played in the minors, he made a major contribution in helping a top pitching prospect get acclimated to baseball in the United States.

From Mexico to Mets

A native of Monterrey, Mexico, Trevino was 7 and playing youth baseball when he saw the World Series on television for the first time in 1964, the Cardinals versus the Yankees. “I was impressed so much by Bob Gibson because I was a pitcher then,” Trevino told United Press International.

Trevino was 16 when the Mets signed him in May 1974 with the intention of making him a shortstop. Assigned to a rookie league club in Marion, Va., Trevino became a catcher for manager Chuck Hiller, a future Cardinals coach.

Four years later, Trevino got called up to the Mets and he and Torre bonded.

“To me, he’s like my second father,” Trevino told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. “He took me under his wing when I came to the big leagues. I owe him a lot. He gradually gave me playing time and let me build my confidence.”

Torre said, “He had such great hands. I always like the way he caught.”

Trevino was a backup to John Stearns with the Mets in 1978 and 1979. An agile catcher with a strong throwing arm, Trevino got more starts than Stearns in 1980, but went back to a reserve role in 1981 because Stearns was the better hitter.

Trevino led National League catchers in throwing out the highest percentage of runners attempting to steal in 1979 (47.7 percent) and 1980 (44.3 percent).

Torre said Trevino became the favorite player of his daughter, Tina. Also, Trevino got to be a teammate of his favorite player from the 1964 World Series, Bob Gibson, who became a coach on Torre’s staff with the 1981 Mets.

“Several clubs are interested in Trevino, but Torre won’t part with the kid,” The Sporting News reported.

On the move

After the 1981 season, Torre became manager of the Braves, and the Mets packaged Trevino in a trade to the Reds for slugger George Foster. Trevino took over for future Hall of Famer Johnny Bench, who no longer could catch regularly.

When the Reds opened the 1982 season, Trevino was the catcher and Bench was at third base. Boxscore

A contact hitter with little power, Trevino was no Bench, and he fell into disfavor with the Reds.

“They expected me to hit .300 and throw out every baserunner,” Trevino told The Sporting News. “It was a bad time … They played with my head there.”

In April 1984, the Reds sent Trevino to the Braves to be the backup to Bruce Benedict. Torre was the manager and he “treasured Trevino’s skills,” The Sporting News reported. Also, Bob Gibson was on the coaching staff.

After the 1984 season, Torre was fired and Trevino was traded to the Giants. Trevino went from the Giants (1985) to the Dodgers (1986-87) and to the Astros (1988-90).

On June 13, 1986, Trevino and Dodgers pitcher Fernando Valenzuela formed what is believed to be the first all-Mexican battery in the majors, according to the Los Angeles Times. Boxscore

One of Trevino’s best games came on May 22, 1988, at St. Louis when he got four hits and scored the winning run in the Astros’ 2-1 victory over the Cardinals. Boxscore

Ups and downs

In 1990, Trevino was the backup to Astros catcher Craig Biggio, but in July he was released and replaced by Rich Gedman, who was acquired from the Red Sox.

The Mets signed Trevino in August 1990, but the reunion started badly. In his first start for the Mets, on Aug. 5, 1990, against the Cardinals at St. Louis, Trevino was hitless, committed two errors and allowed two passed balls. Boxscore

“It was the worst game of my career,” Trevino told the Post-Dispatch. “I’ve never had a day like that.”

A month later, the Reds selected Trevino off waivers. Trevino got three hits in seven at-bats for the Reds, who went on to become 1990 World Series champions.

Change in plans

Trevino became a free agent in December 1990 and the Cardinals arranged for him to reunite with Torre again. The Cardinals had decided to move Todd Zeile from catcher to third base, and were seeking a veteran backup to Tom Pagnozzi, who became the starting catcher.

The Cardinals also had considered Gary Carter (36) and Ernie Whitt (38) as the backup catcher but took Trevino (33) because he was younger, the Post-Dispatch reported. Carter signed with the Dodgers and Whitt went with the Orioles.

Cardinals general manager Dal Maxvill, who had been a coach on Torre’s staffs with the Mets (1978) and Braves (1984) when Trevino was there, said, “We’re not trying to look beyond this year, but, if the guy is still catching decently and throwing decently, it could be something beyond a year. I’m not ruling out he could be here four or five years.”

A month later, the Cardinals signed Rich Gedman, the catcher who in 1990 had replaced Trevino on the Astros, to a minor-league contract. “Gedman figures to be Louisville’s starting catcher this season unless he beats out Alex Trevino for the backup catching job” with the Cardinals, the Post-Dispatch reported.

At Cardinals spring training in 1991, Trevino was “erratic on defense,” according to the Post-Dispatch. Gedman, a left-handed batter, hit .375. Trevino, a right-handed batter, hit .353.

Torre liked having a catcher who batted left-handed to back up Pagnozzi, who hit from the right side. On March 31, 1991, Torre told Trevino he was being placed on waivers for the purpose of giving him his release. “It was hard, really hard,” Torre said of his talk with Trevino.

A stoic Trevino said, “Gedman had a good spring. It was obvious.”

Keep on going

Trevino signed a minor-league contract with the Angels and was assigned to their Class AA club at Midland, Texas, where he was reunited with Fernando Valenzuela, who was attempting a comeback.

After playing in 14 games for Midland, Trevino joined his hometown team, Monterrey, in the Mexican League.

In February 1992, the Cardinals invited Trevino to spring training as a non-roster player, and he earned a spot with their Louisville farm club.

The Cardinals had signed a promising pitching prospect, Cuban defector Rene Arocha, and assigned him to Louisville. Trevino caught most of Arocha’s games, served as his interpreter and mentored him.

In September 1992, after the end of Louisville’s season, Trevino was rewarded for his effort. He was called up to the Cardinals, though not activated, and spent the final month of the season in the big leagues.

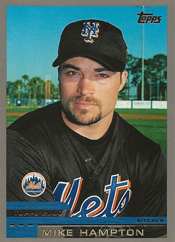

In December 2000, the Cardinals thought Hampton, a left-handed pitcher and free agent, would accept their offer of a seven-year contract for $91 million.

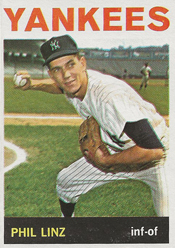

In December 2000, the Cardinals thought Hampton, a left-handed pitcher and free agent, would accept their offer of a seven-year contract for $91 million. A utility player during the regular season, Linz started all seven games of the Series for the Yankees as their shortstop and leadoff batter.

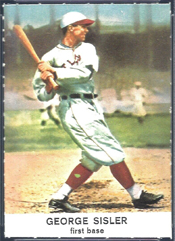

A utility player during the regular season, Linz started all seven games of the Series for the Yankees as their shortstop and leadoff batter. On Dec. 13, 1930, Sisler signed with the Rochester Red Wings, a Cardinals farm club, to be their first baseman after 15 seasons in the majors with the Browns, Senators and Braves.

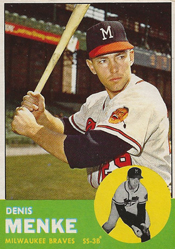

On Dec. 13, 1930, Sisler signed with the Rochester Red Wings, a Cardinals farm club, to be their first baseman after 15 seasons in the majors with the Browns, Senators and Braves. Menke was an infielder who played 13 seasons with the Braves (1962-67), Astros (1968-71, 1974) and Reds (1972-73). He also coached in the majors for 20 years.

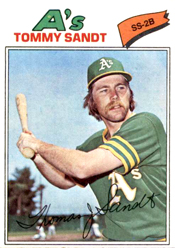

Menke was an infielder who played 13 seasons with the Braves (1962-67), Astros (1968-71, 1974) and Reds (1972-73). He also coached in the majors for 20 years. Though he never played in the majors for the Cardinals, Sandt was in their farm system after being acquired from the Athletics.

Though he never played in the majors for the Cardinals, Sandt was in their farm system after being acquired from the Athletics.