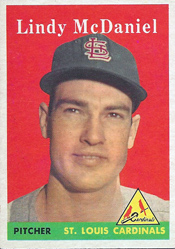

Though the Cardinals put Lindy McDaniel on their team because they had to, he showed he deserved to be there.

A right-hander who developed into a quality reliever and pitched 21 seasons in the major leagues, McDaniel was 19 when he got to the big leagues with the Cardinals as a teammate of Stan Musial in 1955. He was 39 when he pitched his final game with the Royals as a teammate of George Brett in 1975.

A right-hander who developed into a quality reliever and pitched 21 seasons in the major leagues, McDaniel was 19 when he got to the big leagues with the Cardinals as a teammate of Stan Musial in 1955. He was 39 when he pitched his final game with the Royals as a teammate of George Brett in 1975.

In addition to Cardinals (1955-62) and Royals (1974-75), McDaniel pitched for Cubs (1963-65), Giants (1966-68) and Yankees (1968-73).

McDaniel led the National League in saves three times: twice with the Cardinals (1959 and 1960) and once with the Cubs (1963). He had a career record in the majors of 141-119 with 174 saves.

One of his most important wins was his first. It came when he was 20 years old and it helped convince the Cardinals his spot on the club was warranted.

Prime prospect

McDaniel was 19 when he signed with the Cardinals for $50,000 on Aug. 19, 1955. Because of the amount he received, the Cardinals were required by a baseball rule at the time to keep McDaniel on the big-league club for at least the next two years.

The Cardinals signed McDaniel on the recommendation of scout Fred Hawn, who called him “the best pitching prospect, maybe the best player, I’ve ever scouted for the Cardinals.,” the St. Louis Globe-Democrat reported. “His fastball and his curve are alive and he gets them over the plate.”

An amateur baseball standout in Oklahoma, McDaniel had been pursued by the Cardinals since he was 16 in 1952. He attended the University of Oklahoma for a year, but left to join the Cardinals, “fulfilling a childhood ambition to play with Dizzy Dean’s old club and alongside his idol, Musial,” the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported.

The Phillies, Dodgers, Reds, Yankees, Indians and Red Sox also wanted to sign McDaniel, but “when I found out the Cardinals were interested, I told the others not to bother,” McDaniel said to The Sporting News. “They’re a team of the future with a young staff. I’ll get more chances to pitch with them than with other clubs.”

When Lindy and his father, Newell McDaniel, an alfalfa and cotton farmer, went to St. Louis for the contract signing, Lindy let his dad do most of the talking.

“He don’t talk much,” Newell said to the Post-Dispatch. “You won’t get much out of him. He concentrates on training. He’s one of those boys just born that way, not interested in girls or anything. Exercises every night before retiring. He’s a fanatic.”

According to The Sporting News, Lindy invested part of the signing bonus in purchasing a 160-acre farm near his home in Hollis, Okla., and turning it over to his father to tend.

Teen dream

McDaniel reported to the Cardinals on Sept. 1, 1955, and he made his debut in the majors the next day at Chicago. McDaniel, 19, entered in the seventh inning with the Cubs ahead, 11-1, and the second batter he faced, Walker Cooper, 40, hit a home run. McDaniel regrouped and didn’t allow another run over two innings. Boxscore

“That boy may never have to go down to the minors,” Cardinals manager Harry Walker told the Post-Dispatch.

On Sept. 19, 1955, McDaniel got his first start in the majors against the Cubs at St. Louis. He gave up a grand slam to Ernie Banks, making him the first player in the majors to hit five in one season. McDaniel gave up five runs, 10 hits and four walks in seven innings, but didn’t get a decision after the Cardinals rallied to win. Boxscore

McDaniel made four September appearances for the 1955 Cardinals and was 0-0 with a 4.74 ERA. According to The Sporting News, he “demonstrated he might be just more than ornamental in 1956.”

On his way

The Cardinals changed managers after the 1955 season, hiring Fred Hutchinson, a former pitcher, to replace Harry Walker.

McDaniel didn’t pitch much at spring training in Florida, but Hutchinson told The Sporting News, “I saw enough of him to know he had good stuff.”

As the Cardinals headed north from Florida to open the season, they were scheduled to play an exhibition game against the White Sox at Oklahoma City. McDaniel was supposed to pitch before a big crowd in his home state, but the game was canceled because of bad weather.

In the Cardinals’ final exhibition game at Kansas City two days before the season opener, McDaniel pitched two scoreless innings against the Athletics.

After losing two of their first three games of the regular season, the Cardinals were home to play the Braves on April 21, 1956, a Saturday afternoon.

With the Braves ahead, 5-3, McDaniel made his first appearance of the season, entering in the fifth inning in relief of starter Willard Schmidt.

Hutchinson “appeared to be taking a long gamble by bringing in a kid” whose “total professional experience consisted of 19 innings last September,” the Post-Dispatch reported, but Hutchinson “had been impressed with Lindy’s poise and potential.”

McDaniel rewarded his manager’s faith in him, retiring 12 of the 15 Braves batters he faced and pitching five scoreless innings. The Cardinals rallied for a 6-5 victory, giving McDaniel his first win in the majors.

A turning point came in the eighth inning. Eddie Mathews led off with a single and Hank Aaron walked, but catcher Bill Sarni made a snap throw to first baseman Wally Moon, picking off Aaron. McDaniel struck out Bobby Thomson and got Joe Adcock to ground out, ending the threat. He retired the side in order in the ninth.

“The kid did great,” Hutchinson said. Boxscore

Plate umpire Babe Pinelli told the Sporting News, “He showed one of the best curves I’ve ever seen and I’ve been in baseball 40 years. He doesn’t scare. He looks nerveless.”

Family affair

The win gave McDaniel a considerable boost. He was 4-0 with a 2.83 ERA entering June. Hutchinson tried him as a starter, but it didn’t work out. McDaniel finished the season at 7-6. He was 5-2 with a 2.58 ERA in 32 relief appearances and 2-4 with a 5.25 ERA in seven starts.

The next year, the Cardinals signed Lindy’s brother, Von McDaniel, 18, for $50,000 and he joined Lindy on the big-league club.

Von won his first four decisions with the 1957 Cardinals, finished 7-5 and flamed out.

Lindy was 66-54 with 66 saves in eight seasons with the Cardinals before he was traded with Larry Jackson and Jimmie Schaffer to the Cubs for George Altman, Don Cardwell and Moe Thacker on Oct. 17, 1962.

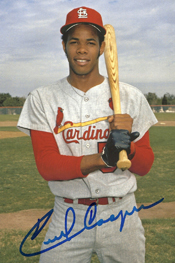

On Nov. 30, 1970, the Cardinals chose Cooper in the Rule 5 draft. Cooper, 20, was the Midwest League batting champion in 1970, but the Red Sox didn’t put him on their 40-man major-league winter roster, leaving him eligible to be drafted by another organization.

On Nov. 30, 1970, the Cardinals chose Cooper in the Rule 5 draft. Cooper, 20, was the Midwest League batting champion in 1970, but the Red Sox didn’t put him on their 40-man major-league winter roster, leaving him eligible to be drafted by another organization. On Nov. 30, 2010, the Cardinals traded pitcher Blake Hawksworth to the Dodgers for Theriot.

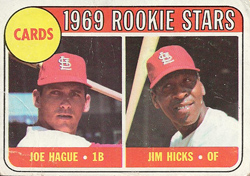

On Nov. 30, 2010, the Cardinals traded pitcher Blake Hawksworth to the Dodgers for Theriot. Though he hit for power and average in the minors, Hicks primarily was a reserve player in brief stints in the majors with the White Sox, Cardinals and Angels. A right-handed slugger, he began the 1969 season as a backup outfielder for the Cardinals.

Though he hit for power and average in the minors, Hicks primarily was a reserve player in brief stints in the majors with the White Sox, Cardinals and Angels. A right-handed slugger, he began the 1969 season as a backup outfielder for the Cardinals. On Nov. 30, 1970, the Cardinals acquired reliever Moe Drabowsky from the Orioles for infielder Jerry DaVanon.

On Nov. 30, 1970, the Cardinals acquired reliever Moe Drabowsky from the Orioles for infielder Jerry DaVanon. On Nov. 29, 1950, Marion was chosen by Cardinals owner Fred Saigh to replace manager Eddie Dyer, who resigned. The hiring came two days before Marion turned 33.

On Nov. 29, 1950, Marion was chosen by Cardinals owner Fred Saigh to replace manager Eddie Dyer, who resigned. The hiring came two days before Marion turned 33.