(Updated March 10, 2022)

Tony La Russa, thought by some to be too old to manage in the majors, once was thought to be too young.

On Aug. 3, 1979, La Russa was 34 when he managed his first game in the majors for the White Sox. On Oct. 29, 2020, La Russa was 76 when he was named White Sox manager for a second time.

On Aug. 3, 1979, La Russa was 34 when he managed his first game in the majors for the White Sox. On Oct. 29, 2020, La Russa was 76 when he was named White Sox manager for a second time.

When he joined the White Sox at 34, La Russa’s managerial experience consisted of two partial seasons in the minors.

When he rejoined the White Sox at 76, La Russa’s managerial experience consisted of a Hall of Fame resume, including leading the Cardinals to three National League pennants and two World Series championships. He ranks No. 1 all-time in wins (1,408) among Cardinals managers.

La Russa managed the White Sox from 1979-86, Athletics from 1986-95 and Cardinals from 1996-2011 before taking on a variety of front-office jobs.

His return to managing after an absence of nearly a decade drew surprise and skepticism similar to when the White Sox first hired him.

White Sox welcome

La Russa ended his playing career with the Cardinals’ New Orleans farm team as a player-coach in 1977. When manager Lance Nichols became ill, La Russa replaced him for five games. Cardinals instructor George Kissell asked La Russa whether he wanted to pursue managing as a career.

“He told me, ‘Unless you really get into learning every aspect of it, you’re not cut out for coaching or managing,’ ” La Russa recalled to Stan McNeal of Cardinals Magazine. “That was a real straightforward way to make a decision.”

La Russa was about to finish law school and take his bar exam in Florida, but he wanted to give managing a try.

According to the book, “Tony La Russa: Man on a Mission,” the Cardinals talked to La Russa about managing their rookie league club in Johnson City, Tennessee, but he declined because he wanted to start at a higher level.

Loren Babe, who managed and mentored La Russa with White Sox farm teams in 1975 and 1976, thought La Russa had the ability to manage, and recommended him to White Sox general manager Roland Hemond and farm director Paul Richards.

Acting on Babe’s tip, the White Sox hired La Russa to manage their Class AA Knoxville club in 1978. One of Knoxville’s top players was 19-year-old Harold Baines, who was destined for a Hall of Fame career. After La Russa led Knoxville to a 49-21 record in the first half of the season, he got promoted to first-base coach for the second half on the staff of White Sox manager Larry Doby, who had replaced Bob Lemon on July 1.

Don Kessinger took over for Doby as White Sox player-manager for 1979. According to the “Man on a Mission” book, La Russa could have stayed on the White Sox coaching staff, but he asked to manage the franchise’s top farm club at Des Moines because he believed being a manager there gave him a better chance than a coaching job did to develop into a big-league manager.

Kessinger had trouble getting the White Sox to play hard for him. They had a dreadful June, losing 19 of 28 games. After a seven-game skid dropped the White Sox’s record to 46-60, Kessinger resigned during a lunch meeting with team owner Bill Veeck on a day off, Aug. 2, 1979.

According to the Chicago Tribune, Veeck considered bringing back Bob Lemon to manage, and he also liked former Tigers manager Les Moss, but Veeck concluded they “wouldn’t be fitted to a ballclub that must constantly juggle its lineup.”

Veeck “should have reached for St. Jude,” Chicago Tribune columnist David Condon wrote.

Instead, Veeck reached out to La Russa, whose Des Moines club was 54-51.

Opportunity awaits

Veeck called La Russa in Des Moines and informed him he wanted him to manage the White Sox.

In the 2012 book “One Last Strike,” La Russa said, “Looking back on it, I can see they probably had more trust in me than I did in myself, or maybe as (broadcaster) Harry Caray claimed, they were too cheap to hire a real manager.”

La Russa accepted Veeck’s offer and went to Chicago that night to join the team for their flight to Toronto, where the White Sox would start a series versus the Blue Jays the following night.

“In replacing low-keyed Don Kessinger with keyed-up Tony La Russa, the White Sox may be bringing a new Earl Weaver into the American League,” wrote Richard Dozer in the Chicago Tribune. “La Russa is tough, dedicated to winning at any cost, and probably won’t keep Chicago fans waiting long to see an emotional outburst that would make Leo Durocher look like a Sunday school teacher.”

La Russa told the newspaper, “I’m a hungry manager. I have this fire that burns inside me, and it tells me I want to win any way I can.”

La Russa also acknowledged, “One of the things I’m going to have to do is learn to control my temper. I’ve made moves in anger that I might not make otherwise. You lose your temper and you lose your good sense.”

Winning start

Before his first game as White Sox manager, La Russa held a 35-minute meeting with the team. According to the “Man on a Mission” book, he told them, “Don’t embarrass me, and I won’t embarrass you. Play hard all the time. Come to me any time you want to talk.”

Third baseman Kevin Bell told United Press International, “We talked over the club’s problems in a meeting before the game. We all pretty much agreed we had been dogging it on a few occasions.”

White Sox pitcher Steve Trout said La Russa inspired everybody “with that little speech before the game,” the Chicago Tribune reported.

Bell, Jim Morrison and Lamar Johnson hit home runs, sparking the White Sox to an 8-5 triumph over the Blue Jays. Trout pitched eight innings for the win and Ed Farmer pitched a scoreless ninth for the save. Boxscore

The White Sox were 27-27 for La Russa in 1979. They contended in 1982, with 87 wins, and in 1983 they had the best record in the majors (99-63) and qualified for the postseason for the first time since 1959.

Flood hadn’t played in a game since Oct. 2, 1969, with the Cardinals. Five days later, the Cardinals

Flood hadn’t played in a game since Oct. 2, 1969, with the Cardinals. Five days later, the Cardinals  On Nov. 2, 1995, Torre, 55, was hired to manage the Yankees, who, to his surprise, approached him about replacing Buck Showalter.

On Nov. 2, 1995, Torre, 55, was hired to manage the Yankees, who, to his surprise, approached him about replacing Buck Showalter. On Dec. 14, 1970, Hill, 25, drowned while swimming in the sea in Venezuela.

On Dec. 14, 1970, Hill, 25, drowned while swimming in the sea in Venezuela. He was a highly regarded prospect who experienced personal tragedy soon after he got to the majors.

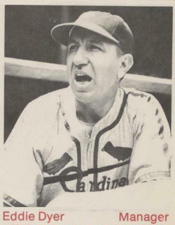

He was a highly regarded prospect who experienced personal tragedy soon after he got to the majors. On Oct. 16, 1950, after five seasons as Cardinals manager, Dyer, 51, resigned rather than wait for club owner Fred Saigh to make a change.

On Oct. 16, 1950, after five seasons as Cardinals manager, Dyer, 51, resigned rather than wait for club owner Fred Saigh to make a change.