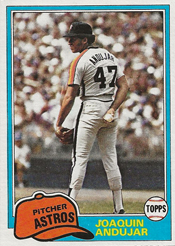

Joaquin Andujar, a big winner for the Cardinals when they became World Series champions in 1982 and again when they won another National League pennant in 1985, might never have pitched for them if the Astros and Pirates had closed a deal involving him.

In 1980, the Astros agreed to trade Andujar to the defending World Series champion Pirates for first baseman and outfielder Bill Robinson. The deal was to be completed just before the start of 1980 spring training, but it fell through when the Astros refused to renegotiate Robinson’s contract.

In 1980, the Astros agreed to trade Andujar to the defending World Series champion Pirates for first baseman and outfielder Bill Robinson. The deal was to be completed just before the start of 1980 spring training, but it fell through when the Astros refused to renegotiate Robinson’s contract.

A few months later, the Astros planned to trade Andujar to the Phillies as part of a three-way deal with the Giants, but it didn’t happen because the player the Astros wanted in return went on the disabled list.

Andujar finished the 1980 season with the Astros and was traded to the Cardinals in 1981.

Wrong role

The Astros began the 1979 season with Andujar in the bullpen. He moved into the rotation in late May. In six June starts, Andujar was 5-1 with a 1.59 ERA, but he was ineffective late in the season and manager Bill Virdon put him back into a relief role.

“I’m the only guy that has to win every time and, if I don’t, I’m in the bullpen,” Andujar complained to The Sporting News. “If I don’t win there, I’m in the doghouse. They forget me. They ought to trade me or give me my release.”

Andujar completed the 1979 season with a 12-12 record, four saves and a 3.43 ERA. He made 23 starts and 23 relief appearances.

After the season, the Astros signed free agent Nolan Ryan, who joined a rotation of Joe Niekro, J.R. Richard and Ken Forsch.

The Astros put Andujar on the trade market. They were seeking a first baseman who could hit with power from the right side to replace Cesar Cedeno, who wanted to return to the outfield.

The Braves showed interest, but they also were in discussions with the Cardinals about a swap of outfielder Gary Matthews for pitcher John Denny and catcher Terry Kennedy, The Sporting News reported.

Near deal

At the baseball winter meetings in December 1979, the Pirates became the prime suitor for Andujar. The Pirates wanted a starting pitcher because one of their starters, Bruce Kison, became a free agent and signed with the Angels, and two others, Don Robinson and Rick Rhoden, had undergone shoulder surgeries.

The Pirates offered Bill Robinson to the Astros. In 1979, he hit 24 home runs. He also batted .311 versus left-handers.

“Bill Robinson would help us very much,” Virdon told the Pittsburgh Press.

The deal “came close” to being made, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reported, until the Astros asked for a minor-league player to be included.

According to The Sporting News, the Pirates also discovered Robinson had the right to veto a trade because he had played 10 seasons in the majors, including five in a row with them. Pirates general manager Harding Peterson hadn’t discussed the deal with Robinson, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reported.

The teams decided to halt negotiations.

Called off

Two months later, in February 1980, the Astros and Pirates resumed talks and agreed to a straight swap of Andujar for Robinson. The Pirates planned for Andujar, who turned 27 in 1980, to join a rotation with Bert Blyleven, John Candelaria and Jim Bibby.

The deal hinged on one last step: It needed Robinson’s approval.

Initially, Robinson told The Sporting News, “If Houston still wants me, I want to play for them. I want to play every day and help bring them a pennant.”

He told the Pittsburgh Press, “I’ve tentatively agreed to the trade.”

The clubs gave Robinson a deadline of 5 p.m. on Feb. 20, 1980, to make a firm decision.

Robinson, who turned 37 in 1980, had a contract for the 1980 season and wanted the Astros to extend it through 1981.

Astros general manager Tal Smith refused to renegotiate, so Robinson blocked the trade.

“I vetoed the deal with the Astros because, they not only didn’t offer me an additional penny, they wouldn’t give me a 1981 contract,” Robinson said.

Phillies fuel interest

When Andujar arrived at Astros training camp in Cocoa, Fla., he discovered pranksters had placed a picture of Bill Robinson at his locker.

Andujar wasn’t laughing when he began the regular season in the bullpen. His first start of the 1980 season came on May 24 as a showcase versus the Phillies, who were looking to make a trade to bolster their rotation.

The Phillies were considering a trade of first baseman Keith Moreland, outfielder Lonnie Smith and two minor-leaguers to the Giants for first baseman Mike Ivie and pitchers Ed Halicki and Gary Lavelle, the Philadelphia Daily News reported. The Phillies would send Ivie to the Astros for Andujar.

The deal dissolved when Ivie went on the disabled list for mental fatigue. “He was the whole key, the only player Houston really wanted for Andujar,” wrote Bill Conlin in the Philadelphia Daily News.

Andujar finished the season with a 3-8 record for the 1980 Astros, who won a division title.

The Pirates were glad they didn’t trade Bill Robinson. He hit .287 for them in 1980, including .323 versus left-handers.

In 1981, Andujar was 2-3 with a 4.94 ERA when the Astros traded him to the Cardinals on June 7 for outfielder Tony Scott.

Andujar earned 15 regular-season wins for the 1982 Cardinals and also was the winning pitcher in Games 3 and 7 of the World Series versus the Brewers.

Andujar won 20 for the Cardinals in 1984 and 21 in 1985. After a temper tantrum led to his ejection from Game 7 of the 1985 World Series against the Royals, Andujar was traded by the Cardinals to the Athletics.

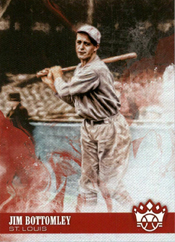

The Cardinals beat the Cubs, 8-7, in 20 innings on Aug. 28, 1930, at Wrigley Field in Chicago.

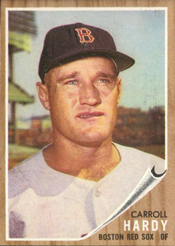

The Cardinals beat the Cubs, 8-7, in 20 innings on Aug. 28, 1930, at Wrigley Field in Chicago. On April 11, 1962, the first time he played in a major-league game, Taylor got the start against the Red Sox at Boston’s Fenway Park, pitched 11 shutout innings and lost when he gave up a walkoff grand slam to Carroll Hardy in the 12th.

On April 11, 1962, the first time he played in a major-league game, Taylor got the start against the Red Sox at Boston’s Fenway Park, pitched 11 shutout innings and lost when he gave up a walkoff grand slam to Carroll Hardy in the 12th. An accomplished athlete from Sturgis, South Dakota, Hardy had a tryout with the baseball Cardinals after he graduated from high school and got a contract offer from them, according to the

An accomplished athlete from Sturgis, South Dakota, Hardy had a tryout with the baseball Cardinals after he graduated from high school and got a contract offer from them, according to the  On Aug. 27, 1980, Kittle, a minor-league pitching instructor for the Cardinals, pitched an inning as the starter for their Springfield (Ill.) farm club.

On Aug. 27, 1980, Kittle, a minor-league pitching instructor for the Cardinals, pitched an inning as the starter for their Springfield (Ill.) farm club. On Aug. 27, 1990, Cardinals pitcher Frank DiPino and catcher Tom Pagnozzi were found not guilty of misdemeanor charges of disorderly conduct. The jury of three women and three men deliberated for 30 minutes before returning the verdicts.

On Aug. 27, 1990, Cardinals pitcher Frank DiPino and catcher Tom Pagnozzi were found not guilty of misdemeanor charges of disorderly conduct. The jury of three women and three men deliberated for 30 minutes before returning the verdicts. After the game, Mathews, DiPino and Pagnozzi went to The Waterfront, a floating restaurant tied to moorings at Pete Rose Pier in Covington. The high-end steak and seafood place had stunning views of the Cincinnati skyline, a lively bar scene and a 1980s “Miami Vice” vibe.

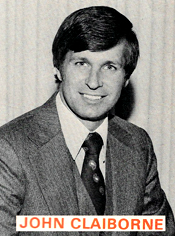

After the game, Mathews, DiPino and Pagnozzi went to The Waterfront, a floating restaurant tied to moorings at Pete Rose Pier in Covington. The high-end steak and seafood place had stunning views of the Cincinnati skyline, a lively bar scene and a 1980s “Miami Vice” vibe. In what the St. Louis Post-Dispatch described as “a surprise move,” Busch fired Claiborne on Aug. 18, 1980, citing “basic disagreements” between the two “regarding progress of the team in all areas of operation.” Two weeks later, Herzog was promoted from manager to general manager.

In what the St. Louis Post-Dispatch described as “a surprise move,” Busch fired Claiborne on Aug. 18, 1980, citing “basic disagreements” between the two “regarding progress of the team in all areas of operation.” Two weeks later, Herzog was promoted from manager to general manager.