It took until 1964 for all the teams in the major leagues to have integrated housing for their players at spring training.

On March 4, 1964, the Minnesota Twins became the last club in the big leagues to end segregation of blacks and whites in spring training residences. The move came 99 years after the end of the Civil War and four months before enactment of the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964.

On March 4, 1964, the Minnesota Twins became the last club in the big leagues to end segregation of blacks and whites in spring training residences. The move came 99 years after the end of the Civil War and four months before enactment of the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Twins owner Calvin Griffith acted after civil rights groups planned to picket the regular-season home opener in protest of the segregated housing.

Racism and inequality

In Orlando, where the Twins trained, their white players, manager, coaching staff and front-office personnel stayed at the Cherry Plaza Hotel on Lake Eola in downtown Orlando.

Because the Cherry Plaza discriminated against blacks, the Twins’ black players stayed at the Hotel Sadler. Located on West Church Street, it was described by the Orlando Sentinel as “the first hotel for blacks in central Florida.”

Most major-league teams training in Florida were slow to end segregated housing. In St. Petersburg, where the Cardinals trained, their black players stayed at a boarding house, and their white players stayed in a waterfront hotel. In 1961, activist Dr. Ralph Wimbish and Cardinals first baseman Bill White led the effort to get Cardinals owner Gussie Busch to end the segregated housing. Unable to find a suitable integrated hotel, the Cardinals leased a St. Petersburg motel and had the entire team and their families stay there.

Three years later, under duress, Calvin Griffith and the Twins did it differently.

High-rise hotel

In 1950, the Eola Plaza apartments opened in Orlando. The nine-story building was one of the tallest in the region, and nearly every room offered a view.

Businessman William Cherry bought the building in the mid-1950s and converted it into a hotel, the Cherry Plaza. It featured a nightclub, the Bamboo Room, and banquet facility, the Egyptian Room.

Calvin Griffith considered the Cherry Plaza to be the best hotel in Orlando. The Twins arranged to make it their spring training headquarters, even though the Cherry Plaza wouldn’t allow blacks to stay there.

Bellman to boss

In 1963, Henry Sadler, who had been a bellman at the San Juan Hotel in downtown Orlando, opened the Hotel Sadler, a two-story turquoise and white structure. According to the Orlando Sentinel, Sadler built the hotel with financial help from Calvin Griffith.

The Hotel Sadler became a mecca for black baseball players and entertainers such as Ray Charles and James Brown, Sadler’s daughter, Paula, told the newspaper.

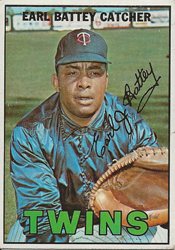

“I have as good a room at the Sadler as I have anywhere in the American League,” Twins catcher Earl Battey told The Sporting News.

Speaking out

Earl Battey liked the Hotel Sadler, but he and his black teammates objected to being segregated. “Our position was that equal but separate accommodations was still discrimination,” Battey told the Minneapolis Star-Tribune.

Another black Twins player, outfielder Lenny Green, said to The Sporting News, “We wanted to be treated like any other player.”

Minnesota Gov. Karl Rolvaag appointed a three-member review board to investigate charges of discrimination against black Twins players at spring training, The Sporting News reported. Rolvaag appointed the panel after Minnesota’s State Commission Against Discrimination ordered a public hearing.

Minnesota attorney general Walter Mondale, the future vice president of the United States, spoke out against the Twins’ segregated conditions.

Minneapolis mayor Arthur Naftalin was informed the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) and the Congress of Racial Equality planned to picket the Twins’ regular-season home opener unless integrated housing was provided to the team. Naftalin called Griffith and urged him to “lay down the law” to Cherry Plaza Hotel management and insist they admit blacks, the Minneapolis Star-Tribune reported.

Quality inns

On Feb. 10, 1964, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964, prohibiting discrimination in public accommodations on the basis of race, color, religion or national origin. The proposal needed approval of the U.S. Senate before President Lyndon Johnson could enact it.

Griffith said he tried to convince Cherry Plaza Hotel manager Frank Flynn to accept blacks, but Flynn refused. Griffith said he and traveling secretary Howard Fox looked into other Orlando lodgings, and all except the Cherry Plaza and the Robert Meyer Motor Inn, which opened on Lake Eola in 1963, were objectionable. Like the Cherry Plaza, the Robert Meyer Motor Inn wasn’t integrated.

“There are two first-class hotels in Orlando and neither will accept Negroes,” Griffith told the Minneapolis Star-Tribune. “That’s all there is to it. Sure, there are places integrated in Orlando, but they’re nothing we would stop at. We’re not going to go to a third- or fourth-rate hotel just to accommodate the civil rights people. If we’re going to integrate, let’s go first class.”

Orlando mayor Robert Carr said it was “ridiculous” to claim good integrated accommodations were unavailable in the city.

With Griffith unwilling to take the team out of the Cherry Plaza Hotel, civil rights groups went ahead with plans for demonstrations to show “our displeasure with the team’s management for not making a strong effort to change the discrimination policy,” said Minneapolis NAACP president Curtis Chivers.

“The Negro members of the team aren’t in a position to do too much and it’s the responsibility of civil rights groups to act in their behalf,” Chivers said.

Making the move

Howard Fox indicated the threat of pickets provided the impetus for Twins management to find integrated housing, The Sporting News reported.

Twins players, coaches and manager Sam Mele were moved to the Downtowner Motor Inn, a chain motel in downtown Orlando. The motel had been integrated since it opened 15 months earlier.

Unmarried players and married players whose wives were not at spring training were moved to the Downtowner. Married players with wives present were allowed to make their own arrangements. Griffith and others in the Twins front office remained in the Cherry Plaza Hotel, The Sporting News reported.

A total of 27 members of the Twins’ team, including a half-dozen blacks, moved to the integrated motel, the Minneapolis Star-Tribune reported.

“We had to give up a little in the quality of accommodations,” Griffith told the Minneapolis newspaper. “As a matter of fact, neither the white nor the Negro players will have quite such commodious quarters as when they were separated, but we have accomplished the primary purpose of bringing our players together without discrimination.”

It’s a small world after all

On June 19, 1964, the U.S. Senate passed the Civil Rights Act. It was signed into law by President Johnson on July 2, 1964.

Three months later, on Oct. 25, 1964, President Johnson visited Orlando and stayed at the Cherry Plaza Hotel, which integrated after passage of the Civil Rights Act.

At spring training in 1965, all of the Twins were housed at the Cherry Plaza Hotel. The Twins went on to win the 1965 American League pennant.

On Nov. 15, 1965, a month after the Dodgers beat the Twins in Game 7 of the World Series, Walt Disney held a news conference in the Egyptian Room of the Cherry Plaza Hotel and announced plans for the creation of Disney World.

On Aug. 16, 1990, during a game between the Astros and Cardinals at Busch Memorial Stadium in St. Louis, Guerrero got upset with Darwin for throwing a pitch too close to him.

On Aug. 16, 1990, during a game between the Astros and Cardinals at Busch Memorial Stadium in St. Louis, Guerrero got upset with Darwin for throwing a pitch too close to him. On Aug. 12, 1970, Gibson pitched 14 innings for a complete-game win in the Cardinals’ 5-4 victory over the Padres in St. Louis.

On Aug. 12, 1970, Gibson pitched 14 innings for a complete-game win in the Cardinals’ 5-4 victory over the Padres in St. Louis. A right-hander, Sebra pitched in the majors with the Rangers (1985), Expos (1986-87), Phillies (1988-89), Reds (1989) and Brewers (1990).

A right-hander, Sebra pitched in the majors with the Rangers (1985), Expos (1986-87), Phillies (1988-89), Reds (1989) and Brewers (1990). The helicopter carrying McCarver in January 1968 veered in time to avoid a collision with Big Savage Mountain, about 20 miles west of Cumberland, Maryland, near the Pennsylvania border.

The helicopter carrying McCarver in January 1968 veered in time to avoid a collision with Big Savage Mountain, about 20 miles west of Cumberland, Maryland, near the Pennsylvania border. On March 4, 1964, the Minnesota Twins became the last club in the big leagues to end segregation of blacks and whites in spring training residences. The move came 99 years after the end of the Civil War and four months before enactment of the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964.

On March 4, 1964, the Minnesota Twins became the last club in the big leagues to end segregation of blacks and whites in spring training residences. The move came 99 years after the end of the Civil War and four months before enactment of the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964. Speaking from Target Field in Minneapolis before the Cardinals played the Twins on July 29, 2020, Mozeliak met for 45 minutes with about a dozen bloggers via Zoom video conferencing to update them on “these unprecedented times” in baseball.

Speaking from Target Field in Minneapolis before the Cardinals played the Twins on July 29, 2020, Mozeliak met for 45 minutes with about a dozen bloggers via Zoom video conferencing to update them on “these unprecedented times” in baseball.