(Updated Dec. 8, 2024)

When Whitey Herzog became Cardinals manager, he replaced a friend who had been his roommate and teammate with the Mets.

On June 8, 1980, the Cardinals fired manager Ken Boyer and hired Herzog to succeed him.

On June 8, 1980, the Cardinals fired manager Ken Boyer and hired Herzog to succeed him.

Boyer, an all-star and Gold Glove Award winner as Cardinals third baseman in the 1950s and 1960s, was their manager since April 1978. Herzog managed the Royals to three consecutive division titles before being fired after the 1979 season.

In 1966, the Mets had Boyer as their third baseman and Herzog as a coach. In his book, “White Rat: A Life in Baseball,” Herzog said he and Ken Boyer shared a New York apartment with Yankees players Roger Maris and Clete Boyer, Ken’s brother.

“When the Mets were on the road, Clete and Roger had the place, and when the Yankees were on the road, Kenny and I took it over,” Herzog said.

After Boyer was fired by the Cardinals, he told a St. Louis Post-Dispatch reporter, “Wish Whitey Herzog good luck. I hope they can turn it around.”

The comment was relayed to Herzog, who said, “I appreciate that. We are very good friends.”

Time for a change

After Herzog left the Royals, Cardinals general manager John Claiborne called him occasionally to seek his opinions on players. Claiborne and Herzog had worked together for Bing Devine with the Mets.

At one point in their conversations, Herzog said, Claiborne asked whether he’d want to become a paid consultant to the Cardinals. “I told him I didn’t want to get tied up with something like that, but I’d be happy to give him my opinions when he asked for them,” Herzog said.

The 1980 Cardinals hit the skids early and Claiborne and club owner Gussie Busch determined Boyer needed to go.

On Saturday, June 7, 1980, Herzog said he got a call from Busch’s attorney, Lou Susman, who asked him to meet Busch in St. Louis the next morning. Meanwhile, Claiborne headed to Montreal, where the Cardinals were playing, to inform Boyer he was fired. Claiborne intended to get to Montreal on Saturday night and meet with Boyer the next morning, but a rainstorm canceled the connecting flight and Claiborne had to spend the night in Chicago.

On the morning of June 8, 1980, Herzog went to Busch’s estate at Grant’s Farm and Claiborne took a flight from Chicago to Montreal, where the Cardinals and Expos were to play a Sunday afternoon doubleheader.

Herzog met with Busch and Susman, and was offered a one-year, $100,000 contract to manage the Cardinals. When Herzog objected to the length of the contract, Busch countered with a three-year deal through the 1982 season. Herzog accepted and Busch made plans to announce the hiring in a news conference late in the afternoon.

(In a 2016 interview with Cardinals Yearbook, Herzog said he was headed out the front door after learning the contract offer was for one year. According to Herzog, Busch then said, “Come back here. You’re right. The ballplayers have long-term contracts; you should have one, too.”)

At Montreal, the Cardinals lost Game 1 of the doubleheader, dropping their record to 18-33 and giving them 21 losses in their last 26 games.

Boyer was in the clubhouse, making out the lineup card for Game 2, when he looked up and was surprised to see Claiborne enter. “I thought for certain he had come here to discuss possible trades,” Boyer told the Montreal Gazette.

Instead, Claiborne told Boyer he was fired. “This is something you want to talk about to a man face to face, not over the telephone,” Claiborne said.

Claiborne offered Boyer another job within the organization, but Boyer said he wanted time to think it over.

“Boyer was on his way to St. Louis by the second inning of the second game,” the Gazette reported.

Coach Jack Krol filled in as manager for Game 2, and the Cardinals lost again.

Mourning in Montreal

In the locker room, after getting swept in the doubleheader, most Cardinals said they were sorry Boyer was gone and exonerated him of blame for the team’s record. Boyer was 166-191 as Cardinals manager.

In comments to the Post-Dispatch, first baseman Keith Hernandez said the 1980 Cardinals were “the worst team I’ve been on since I’ve been in the major leagues. The worst. We are bad. The manager is only as good as his horses and we don’t have the horses. I’m going to miss Ken Boyer.”

Second baseman Tommy Herr said, “There’s a lack of professionalism among certain players as far as guys running groundballs out, 100 percent all-out effort.”

Cardinals catcher Ted Simmons and pitcher Bob Forsch were two of the players most upset by Boyer’s firing, according to the Post-Dispatch. “Old Cardinals die hard,” Simmons said.

Pitcher John Fugham told The Sporting News, “Unfortunately, there were not 25 people on this team as intense as Kenny Boyer was. Therein lies the problem.”

Vern Rapp, who two years earlier was fired while the Cardinals were in Montreal and replaced as manager by Boyer, was a coach with the 1980 Expos. Asked his reaction to Boyer’s firing, Rapp told the Post-Dispatch, “I feel sorry for anybody it happened to. I know how it feels. It’s not a good feeling.”

Oh, brother

At the news conference at Grant’s Farm introducing him as Cardinals manager, Herzog said, “I’m going to take this dang team and run it like I think it should be run. I don’t think I’ve ever had trouble with players hustling. I understand that’s been a problem here. I think you’ll see the Cardinals running out groundballs.”

Asked whether the Cardinals needed a leader to emerge from within the team, Herzog said, “I don’t need a team leader. I’m the leader.”

Said Busch: “My type of manager, without any argument.”

Born and raised in New Athens, Ill., Herzog described himself as a “very opinionated, hardheaded Dutchman.”

At birth, he was named Dorrell Norman Elvert Herzog. His mother said she intended to name him Darrell, but the name got misspelled. In New Athens, where he excelled at basketball as well as baseball, everyone called him Relly. In the New Athens High School yearbook, it was noted, “He likes girls even more than basketball.” As a professional ballplayer, he got nicknamed Whitey because of his light blonde hair.

Herzog had two brothers _ Therron, who everyone called Herman, and Codell, who everyone called Butzy.

When Herzog was named Cardinals manager, Butzy, who “never played baseball in his life,” told Whitey what lineup he should use to help the Cardinals improve.

“I may play his lineup,” Whitey said.

“He better,” Butzy told the Post-Dispatch, “or we’ll have a fight.”

Whether or not it was with Butzy’s help, the Cardinals went on to win three National League pennants and a World Series championship during Whitey’s 11 years as their manager.

Asked about the style of baseball that became known as Whiteyball, Herzog told Cardinals Magazine, “Whiteyball was nothing more than using speed and playing good, sound, fundamental baseball. And your players have to buy in to it.”

Herzog told Cardinals Yearbook, “We changed the way the Cardinals played baseball. We went back to the old Gashouse Gang philosophy.”

I read it and found it to be thought-provoking and informative.

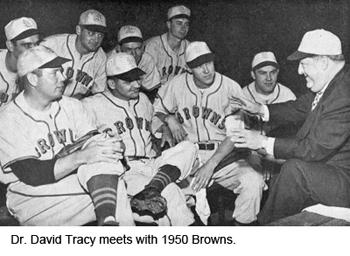

I read it and found it to be thought-provoking and informative. The 1950 Browns slumbered to an 8-25 record before cutting ties with Tracy. They stayed in a stupor, finishing 58-96.

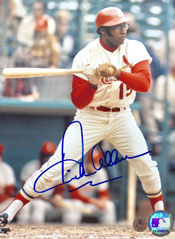

The 1950 Browns slumbered to an 8-25 record before cutting ties with Tracy. They stayed in a stupor, finishing 58-96. On June 2, 1970, Allen had seven RBI for the Cardinals in their 12-1 victory over the Giants at St. Louis.

On June 2, 1970, Allen had seven RBI for the Cardinals in their 12-1 victory over the Giants at St. Louis. On May 29, 1970, the Cardinals acquired reliever Ted Abernathy from the Cubs for infielder

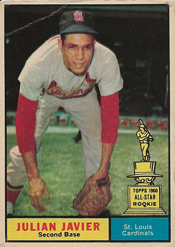

On May 29, 1970, the Cardinals acquired reliever Ted Abernathy from the Cubs for infielder  On May 27, 1960, the Cardinals acquired a pair of Pirates prospects, Javier and reliever

On May 27, 1960, the Cardinals acquired a pair of Pirates prospects, Javier and reliever