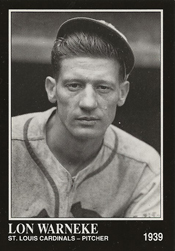

Lon Warneke threw balls and strikes, and wanted to call those pitches, too.

On May 13, 1940, Warneke, a Cardinals pitcher, and Jimmie Wilson, a Reds coach, served as umpires in a game between the teams at Crosley Field in Cincinnati.

On May 13, 1940, Warneke, a Cardinals pitcher, and Jimmie Wilson, a Reds coach, served as umpires in a game between the teams at Crosley Field in Cincinnati.

When National League umpires didn’t show for the game because of a scheduling snafu, one member of each team was chosen to fill in as arbiters.

The Cardinals, given their choice of a Reds representative, selected Wilson, their former catcher who played in three World Series for them. The Reds, asked to pick a member of the Cardinals, chose Warneke, who viewed umpiring as a dream assignment.

“I had a hankering for it even before I started playing baseball,” Warneke told The Sporting News. “Some kids want to become conductors, engineers, policemen, firemen. I wanted to be an umpire.”

Nine years later, Warneke became a full-time National League umpire.

“I like it better than pitching,” Warneke said. “I get just as much satisfaction out of umpiring a good game as I did out of pitching one.”

Failure to communicate

A communication breakdown between Reds management and National League officials created the need for Warneke and Wilson to fill in as umpires for a game.

After the Ohio River flooded and caused the postponement of the Cardinals-Reds game at Cincinnati on April 23, 1940, the teams agreed to a makeup game on Monday, May 13, at 3 p.m.

The date of the rescheduled game made sense. The Reds played the Cardinals in a Sunday doubleheader on May 12 in St. Louis and both clubs were scheduled to use May 13 as an off day before embarking on road trips to the East Coast.

There was only one problem: Reds officials “failed to notify us that the game, postponed from April 23, was to be played,” National League president Ford Frick told the Associated Press.

Therefore, no umpires were assigned.

Help wanted

As game time neared on May 13 and no umpires appeared, Reds officials frantically began making phone calls. One was to Larry Goetz, a National League umpire who lived in Cincinnati.

Goetz, Babe Pinelli and Beans Reardon were the umpires who worked the May 12 Reds-Cardinals doubleheader at St. Louis. The crew’s next scheduled game was May 14, Pirates vs. Giants, at the Polo Grounds in New York. On his way from St. Louis to New York, Goetz stopped home in Cincinnati.

“Goetz was at the railroad station ready to board a 3 o’clock train for New York when they located him,” the St. Louis Globe-Democrat reported.

The start of the game was delayed 29 minutes as the clubs waited for Goetz. During the delay, Warneke and Wilson were recruited to round out the umpiring crew.

Fair and square

It was determined Goetz would work the plate, Wilson would be the umpire at first base and Warneke would be stationed at third.

“Wilson wore an umpire’s cap and a black windbreaker over his uniform shirt,” the Globe-Democrat reported. “Warneke had on his regular uniform topped by a red windbreaker, which he soon discarded for a black one.”

Warneke and Wilson “had numerous close plays to decide on the bases and they turned in a good day’s work,” the Globe-Democrat reported. “Each called plays in critical moments against their own mates.”

For instance, in the second inning the Cardinals had the bases loaded with two outs when Stu Martin hit a line drive to center. Harry Craft raced in, dived headlong, rolled over and thrust his arm above his head to show he had the ball.

Some thought Craft trapped it, but Warneke “majestically called it an out,” the Dayton Daily News reported. “The Cardinals couldn’t plead with their own Honest Lon, and thus the side was retired.”

In the eighth inning, the Cardinals’ Joe Medwick “registered a mild beef against Wilson when he was called out on a close play at first,” the Globe-Democrat reported. Three innings later, when Medwick was called out by Warneke on another close play at second, he showed “his disgust by scooping a handful of dust and throwing it back to the ground. However, Medwick said nothing to Warneke.”

Fit to be tied

The game was noteworthy for more than the unusual umpiring setup. Johnny Mize hit three home runs for the Cardinals and Reds leadoff batter Bill Werber hit four doubles.

Mize’s third home run, a solo shot versus Milt Shoffner with two outs in the top of the 13th, gave the Cardinals an 8-7 lead.

In the bottom half of the inning, backup catcher Williard Hershberger, batting for shortstop Eddie Joost with two outs and none on against Clyde Shoun, doubled. Lee Gamble ran for Hershberger.

Pitcher Bucky Walters, batting for Shoffner, was up next. Walters struck out swinging for what should have been the game-ending out, but catcher Bill DeLancey allowed the ball “to squirt out of his hands and roll into the Cardinals dugout,” the Cincinnati Enquirer reported.

The error enabled Walters to reach first and Gamble to get to third. Jack Russell relieved Shoun and Werber smacked his first pitch for a single, his fifth hit of the game, scoring Gamble with the tying run.

After neither team scored in the 14th, Goetz stopped play at 7 p.m. because of darkness with the score tied at 8-8. Although Crosley Field had lights, a National League rule prohibited lights from being turned on to finish a day game. Boxscore

“It was a game that had everything but a decision at the end of it,” wrote Si Burick of the Dayton Daily News.

All statistics counted, but the tie didn’t count in the standings and the game was scheduled to be replayed as part of an Aug. 11 doubleheader at Cincinnati.

The Cardinals won both games of the Aug. 11 doubleheader, 3-2 and 3-1. Warneke was the winning pitcher in Game 2. The umpires for both games were the three who were supposed to officiate the May 13 game: Goetz, Pinelli and Reardon.

Career change

In July 1942, the Cardinals sold Warneke’s contract to the Cubs, whose manager was his one-time umpiring partner, Jimmie Wilson. Warneke pitched for Wilson in 1942 and 1943.

After finishing his playing career with the 1945 Cubs, Warneke became an umpire in the Pacific Coast League in 1946. He joined the umpiring staff of the National League in 1949 and remained on the job through the 1955 season.

“Hustling, being in the right position to see the plays, and calling them quickly is half the battle in good umpiring,” Warneke told The Sporting News.

“The first and hardest thing I had to learn when I became an umpire was to forget I played ball. As a pitcher, I anticipated where I would throw the ball and what I would do the minute it was hit to me. When I first started umpiring, I did the same thing, anticipating plays, but I soon learned everybody didn’t think like I did. When the play was made, I was often leaning or starting the wrong way. I decided to treat every play, every pitch, as a separate and distinct challenge and handle it accordingly.”

On May 11, 1970, Allen hit a three-run walkoff home run in the bottom of the ninth inning, ending a scoreless duel between future Hall of Famers

On May 11, 1970, Allen hit a three-run walkoff home run in the bottom of the ninth inning, ending a scoreless duel between future Hall of Famers  On May 5, 1990, the Cardinals signed Francona, 31, after he was released by the Brewers and put him on their Class AAA farm club at Louisville.

On May 5, 1990, the Cardinals signed Francona, 31, after he was released by the Brewers and put him on their Class AAA farm club at Louisville. During his 11 NFL seasons (1956-66), all with the Eagles, Retzlaff developed a respect for St. Louis Cardinals safeties Jerry Stovall and Larry Wilson. In 1965, Retzlaff told The Sporting News, “St. Louis has the toughest defensive backs. Larry Wilson was real tough when he played me, but now I find Jerry Stovall even tougher to shake. Jerry has to be the most improved player at his position in the league.”

During his 11 NFL seasons (1956-66), all with the Eagles, Retzlaff developed a respect for St. Louis Cardinals safeties Jerry Stovall and Larry Wilson. In 1965, Retzlaff told The Sporting News, “St. Louis has the toughest defensive backs. Larry Wilson was real tough when he played me, but now I find Jerry Stovall even tougher to shake. Jerry has to be the most improved player at his position in the league.” An outfielder who played in the minors for 14 years, including four in the Cardinals’ system, Frey managed the Royals to their first American League pennant in 1980 and led the Cubs to their first division championship in 1984.

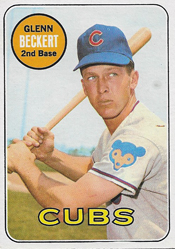

An outfielder who played in the minors for 14 years, including four in the Cardinals’ system, Frey managed the Royals to their first American League pennant in 1980 and led the Cubs to their first division championship in 1984. Beckert was the Cubs’ second baseman from 1965-73 and finished his playing career with the 1974-75 Padres. A four-time all-star, Beckert won a Gold Glove Award in 1968.

Beckert was the Cubs’ second baseman from 1965-73 and finished his playing career with the 1974-75 Padres. A four-time all-star, Beckert won a Gold Glove Award in 1968.